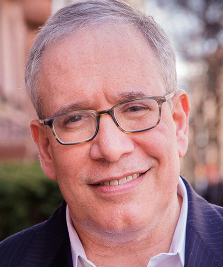

More dedicated bus lanes, a full network of protected bike lanes, a highways-to-parks initiative, permanent open streets, a five borough Citi Bike system, and safe routes for kids to bike to school — these are the buried treasures in City Comptroller Scott Stringer's climate change policy that was released on Sunday.

Most of the 34-page white paper [read it here] focuses on general strategies for reducing the city's greenhouse gas footprint — with a special emphasis on buildings, which account for about 73 percent of city emissions, the report says.

As such, the plan focuses on the big-ticket items: no new fossil fuel infrastructure such as pipelines, clean energy programs in city buildings, investments in renewables, a new public energy utility, tax abatements for properties that install solar arrays, solar cells on city buildings, more support for offshore wind farms, protecting our shoreline with resiliency investments, etc. But the plan also acknowledges the role that safe streets and livable communities can play in the green new world.

For instance, vowing to "improve air quality [by] cutting down on automobile use," Stringer said he would "initiate a comprehensive review of our highway network and will propose specific plans to reduce lanes, deck over existing highway trenches, and promote pedestrian and transit friendly solutions that can take us toward a greener city" with the goal of "scaling back highway infrastructure."

"Urban highways divide our communities, put pedestrians in danger, and drive up rates of asthma and respiratory illness," he argues, citing a statistic that "vehicle emissions are responsible for over 300 premature deaths each year."

The promised review of all aging highways such as the Cross-Bronx and Major Deegan expressways and the Grand Central Parkway builds on Stringer's existing plan to scale back a crumbling stretch of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway into a truck-only highway with a park on top, which he announced in 2019.

The larger goal is to "reduce truck traffic in areas with high rates of asthma," the report said, offering several possible ways to achieve that beyond highway contraction, including creating "incentives to facilitate last mile delivery by bike."

Reducing car use is a key part of Stringer's plan, given that transportation accounts for 28 percent of the city's emissions. He offered several strategies for getting people out of their cars such as support for the open streets program and more protected bike infrastructure, but the single biggest promise is to create dedicated bus lanes for "all high-ridership bus lines," while also offering bus priority at "targeted choke points throughout the city."

Reducing space for car drivers — who are mostly transporting only themselves, plus the 100 square foot of car they're in — in favor of bus passengers is long a dream of the MTA, which called last year for the creation of 60 miles of dedicated bus lanes, but the de Blasio administration promised 20, but then created less than 17.

Stringer promised to "ensure that the streets, traffic lights, curbs, and sidewalks that the city operates will be optimized to give bus riders the fast, reliable, frequent, and accessible service they deserve," the policy paper said.

Some details were lacking. Stringer's plan calls for "making Citi Bike available throughout the five boroughs and free for low-income high school kids," though how he would do that is unclear.

Also, he vowed to create an "ambitious Bike-to-School plan," but details were missing beyond that it would include "a massive expansion of well-designed, well-protected, well-connected bike lanes.

He also vowed to do the unsexy part of building cycling as a mode of transportation, by promising to "actually investing in the maintenance of those lanes so that they’re not pockmarked with potholes, filled with trash, or covered with snow and slush," a reference to a Streetsblog series from late last year about the city's failure to clear bike lanes after the first snowstorm of the season.

"Bike lanes must all extend into environmental justice communities," added Stringer, who has already proposed to subsidize the use of e-bikes.

Stringer is not the first candidate to issue a major policy initiative on the environment or cycling. Last year, former Obama Administration housing secretary Shaun Donovan made transportation one of his first policy rollouts. The Donovan plan was built on several pillars: Creating “true bus rapid transit”; truly embracing cycling and micromobility by broadening access and safety; making roadways safe from reckless drivers.

And 10 of the 11 mayoral candidates responded to Streetsblog's broad transportation questionnaire (which we summarized here). In those surveys, Stringer, Carlos Menchaca and Loree Sutton were most serious about a ban on private car ownership in Manhattan; Dianne Morales said she recognized "the inherent racism in our current car-culture"; and Menchaca said he would eliminate free parking.