This article first appeared in The Appeal, an editorially independent project of The Justice Collaborative which produces original journalism on how policy, politics, and the legal system impact America’s most vulnerable people.

This summer in New York City was defined by protests. The murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer drew hundreds of thousands into the streets in late May and early June, demonstrations that were fueled by violent confrontations with the NYPD in Union Square and downtown Brooklyn.

On May 29, Officer Vincent D’Andraia was filmed throwing Dounya Zayer to the ground and calling her a “stupid fucking bitch.” Zayer suffered a concussion from the incident and also said she later had seizures. Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez charged D’Andraia with third-degree assault, fourth-degree criminal mischief, second-degree harassment and third-degree menacing. New York Attorney General Letitia James apologized to Zayer. After the initial post-George Floyd period and a period of looting of stores in Manhattan and the Bronx, the NYPD adopted a more hands-off stance toward the demonstrations, which have occurred nearly daily.

That silent detente abruptly ended in mid-September. On Sept. 16, in response to a whistleblower claim that Latinx women in ICE custody were involuntarily receiving hysterectomies, daily demonstrations began outside a federal building in Lower Manhattan. Over the course of that week, 134 people were arrested during ICE protests, culminating in the kettling of 86 people in Times Square on Sept. 19 by officers from the Strategic Response Group, the NYPD’s controversial anti-terrorism and protest tactical unit created by former Commissioner Bill Bratton in 2015. “The violence in the enforcement we’ve seen is much more serious than anything we’ve seen in a long time,” Christopher Dunn, the legal director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, told The Appeal. He pointed to the 1988 Tompkins Square Park riot over gentrification and the policing of homelessness as the last comparable instance of widespread NYPD brutality. But the Tompkins Square clashes spanned two days — not several months.

Gideon Oliver, a civil rights attorney who has sued New York City over unlawful mass arrests during the 2004 Republican National Convention and Occupy Wall Street in 2011, said the NYPD’s actions in mid-September are a return to older, more confrontational tactics that include sweeping up large numbers of protesters on questionable legal grounds.

“There was obviously a tremendous and aggressive response to the Floyd protests and the uprisings in the beginning, and then I think there was a shift in tactics until the ICE-related protests in the last week and change,” Oliver said on Sept. 23. For months prior, large street marches went virtually unchallenged by police. “You can observe on the street that there’s been a shift in the way that police treat the protesters,” he said.

The NYPD did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Trump endorsements

The NYPD’s shift in posture toward street protests and the leading role of its Strategic Response Group in recent mass arrests, comes as the city’s two largest police unions have formally endorsed President Trump. As Trump encourages militias and counterprotesters, and defends the actions of lethal attacks on Black Lives Matter demonstrations, some fear that the NYPD’s politicization, return to old tactics, and new department-wide public disorder training being administered on a precinct level portend for a chaotic autumn. The tactical shift is particularly conspicuous after police looked the other way at right-wing counterprotesters who drove cars through mass BLM protests and caused injuries.

Power Malu, a Lower East Side activist who was arrested in Times Square on Sept. 19, said the SRG is a familiar presence at demonstrations, and the unit has targeted specific organizers and groups. “They know who we are, and we know who they are,” he said, adding that the speed and overwhelming show of force of the Times Square arrests surprised organizers.

Commanded by Inspector John D’Adamo, the SRG is composed of more than 700 officers and divided into five borough-based teams plus the Disorder Control Unit (DCU). The unit, which predates the SRG, is known for bringing “hats and bats” (clubs and long batons) to protests and engaging in violent mass arrests of questionable legality. It was central to policing the 2003 anti-war demonstrations, the 2004 Republican National Convention — where over 1,800 people were arrested and held for days without charges, resulting in an $18 million legal settlement — and Occupy Wall Street. The DCU’s tactics included using military-style training to break up crowds through a “disperse and demoralize” strategy, using undercover officers to spread misinformation among crowds, arresting demonstrators early to “set a tone,” and arresting “potential rioters” before they committed crimes.

In addition to protests, the SRG is also used to monitor large parades and public gatherings, and for crime suppression patrols. From its inception, activists were alarmed at the NYPD’s conflation of counterterrorism and protest policing. “Terrorism and protest is what they’re trained to police,” Wylie Stecklow, a civil rights attorney who has represented clients involved in Occupy Wall Street mass arrests, told The Appeal. Stecklow said that when NYPD polices demonstrations they perceive as friendly, like the Blue Lives Matter protest in July in Bay Ridge, they take a hands-off approach. “When they are policing Occupy, the RNC, BLM, then it doesn’t matter if you’re participating in expressive speech activity, they’re not waiting for you to commit civil disobedience before they make that arrest.”

Activists quickly dubbed SRG “the goon squad” — and soon afterward the unit became known for its aggressive conduct and what appeared to be focused surveillance of particularly active protesters and groups. Officer Numael Amador was removed from the unit and suspended for choking two activists during an attempt to stop the deportation of immigration rights activist Ravi Ragbir in the winter of 2018. Even before the Ragbir incident, Amador had 15 Civilian Complaint Review Board complaints on his record, including four substantiated allegations. Also that year, SRG officers were photographed manhandling City Council members Jumaane Williams and Ydanis Rodríguez. The unit has also been criticized for fatal shootings, conducting drunken driving stops, allegedly falsifying DUI charges to meet performance quotas, and backing away when the Proud Boys assaulted anti-fascist protesters outside an October 2018 event in Manhattan.

The Appeal reviewed videos from protests during early June (including mass arrests in Union Square and the South Bronx) and two weeks of sustained clashes with demonstrators in September and identified 62 SRG officers and supervisors. Of the officers identified:

- 46 had complaint histories with the Civilian Complaint Review Board, with an average of two incidents per SRG officer. By comparison, 40 percent of all NYPD personnel had two or more incidents of alleged misconduct.

- 292 misconduct allegations were filed with the CCRB against the 46 SRG officers. Of these, 42 officers racked up 142 abuse of authority complaints. 35 were accused of excessive force. 25 were responsible for 43 discourtesy complaints, and 5 tallied 7 allegations of offensive language.

- 14 supervisors — sergeants, lieutenants, and captains — had multiple misconduct allegations. One SRG supervisor, Lt. Ischaler Grant from SRG 4 in the Bronx, has 32 complaints involving ten separate incidents in his file since joining the NYPD in 1990, including seven substantiated allegations. Only two percent of officers in the NYPD have more incidents of alleged misconduct than Lieutenant Grant.

- SRG 4 had the most officers — 12 — with misconduct allegations. SRG 1 in Manhattan and SRG 2 in Queens both had nine officers with complaint histories, followed by Staten Island’s SRG 5 with six and Brooklyn’s SRG 3 with five.

(The CCRB, it should be noted, substantiates less than 10 percent of misconduct allegations).

Dunn of the NYCLU told The Appeal that the extensive disciplinary records of the SRG officers virtually guaranteed the “poorly conceived” unit would cause problems when put on the front lines of controlling demonstrations. “If you have a unit made up of officers with substantial histories of misconduct, you’re guaranteed to have problems when that unit is assigned to police protests,” Dunn said, adding that supervisors with thick personnel files “are not the people you want running a unit that interacts with protests.”

When the George Floyd protests in New York City began late in the spring, SRG officers deployed “Cobra teams” of bicycle and foot cops that have been front and center in violent clashes with demonstrators. On May 28, the very first demonstration in the city was disrupted by yellow-clad SRG bicycle cops, some of whom bludgeoned demonstrators with their mountain bikes. The Appeal has learned that Officer Yuriy Demchenko of SRG 3 is one of the officers accused of using his bicycle as a weapon, and is the subject of at least two use-of-force complaints.

Detective Craig Jacob of SRG 1 is also facing a use-of-force allegation for wielding his bike as a weapon during the May protests. Since joining the NYPD in 2004, Jacob has amassed 13 CCRB complaints, including two allegations of improperly pointing a weapon and one allegation of racially offensive language.

In 2018, Demchenko was the subject of a civil-rights lawsuit accusing him of falsifying charges against a Coney Island woman whose house was raided in a narcotics sting. According to court records, Demchenko wrote up a criminal complaint claiming that marijuana, crack cocaine, and codeine were found during a search of the woman’s apartment, information gleaned from an anonymous tip. But no narcotics were recovered during the search. The city settled with the woman for approximately $24,000.

Mass arrests

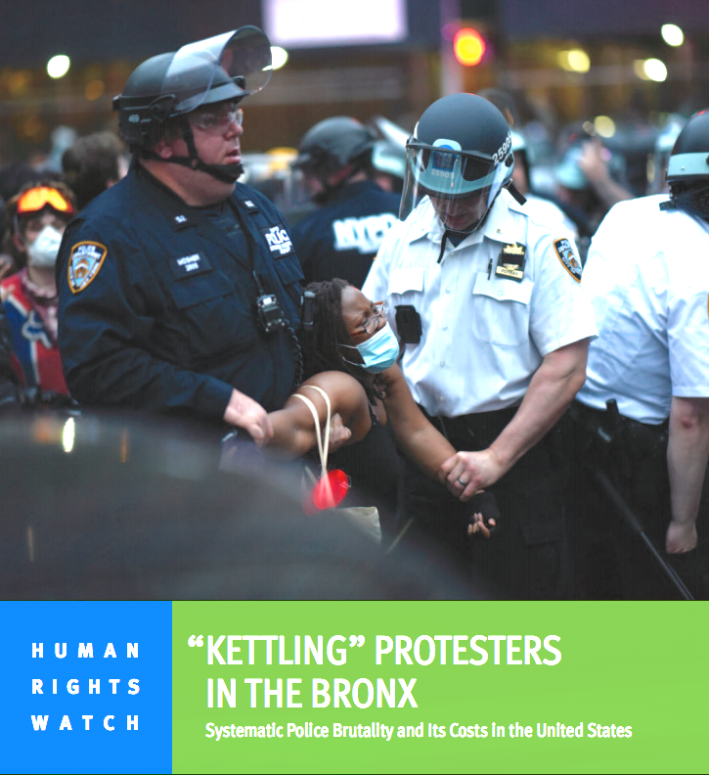

SRG also spearheaded the mass arrest of more than 250 demonstrators, legal observers, and medical workers on June 4 in the South Bronx, during a controversial weeklong citywide curfew. The mass arrests appeared to be orchestrated by Chief of Department Terence Monahan, the highest-ranking uniformed member of the NYPD. Monahan played a prominent role in the 2004 Republican National Convention arrests later ruled unlawful by a United State District Court judge.

Hundreds of demonstrators were diverted off Willis Avenue by a roadblock of 50 officers and then kettled at 136th Street and Brook Avenue by heavily armored SRG bike cops, many of whom had their names and badge numbers concealed. As was the case with the Union Square protests, SRG officers again battered people with their mountain bikes, forcing the crowd of hundreds into a street sealed on both sides by riot officers. Police climbed on cars to strike the crowd with batons. The SRG’s use of their bikes as “weapons” against protesters was highlighted by James, the state attorney general, in a report from her office on the NYPD’s handling of the summer protests.

The following day, Police Commissioner Dermot Shea claimed that the group organizing the march was seeking to hurt officers, not engage in protest. “This wasn’t again about protests, this was about tearing down society,” Shea said. Over 100 demonstrators were injured that evening, according to a Sept. 30 Human Right Watch report on the incident that labeled NYPD’s conduct as “serious violations of international human rights law” and the First Amendment.

Stecklow, the Occupy Wall Street attorney, is representing a dozen people arrested at the June 4 protest. He said the kettle was meant to sow fear and discourage protesters from turning out in the future. “Everyone was afraid of being trampled, contracting the virus, even being killed,” he said. “This was done by design — the next time there’s a protest, people are less likely to go out and join.” Stecklow has two separate civil suits in state courts challenging the NYPD’s policing of sidewalk protests, one of which is heading to trial.

The June 4 protest is the subject of at least 17 separate complaints under investigation by the CCRB. In an Oct. 2 appearance on WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said he had not read the Human Rights Watch report, and “some of that characterization doesn’t sound like what I heard at the time, including from our own observers.”

During the ICE protests in Times Square on Sept. 19, SRG officers quickly kettled several dozen marchers and cyclists, moving first on the bicyclists as they stepped into the street with the walk signal.

“They surrounded the bikers from the back and the front. This was a planned attack on peaceful protesters,” said Luis Galilei, a 27-year-old protester from Harlem who was one of the cyclists tackled and arrested by SRG cops in Times Square. Galilei, who faces a disorderly conduct charge along with the 85 others arrested that day, said the officers pinned him to the ground by pressing their knees into his back.

Video of the Sept. 19 mass arrests obtained by The Appeal show instances of SRG officers — some with extensive disciplinary histories — using force to arrest protesters who sat in the middle of Times Square in an act of mass civil disobedience. Sgt. Keith Hockaday, a former Bronx housing cop now assigned to SRG 2 out of the same borough, is seen using his baton to force activists to submit to handcuffs. Over his career, Hockaday has amassed 16 CCRB complaints, including five use of force allegations. None of the complaints against Hockaday were substantiated. He has also been the subject of at least 10 civil suits, including five cases settled by the city for $91,000 total that include allegations of false arrest, falsifying criminal charges, and illegal searches.

Another SRG supervisor who assaulted Times Square arrestees is Sgt. Steven Gansrow, a former narcotics officer in Brooklyn and Queens with 15 CCRB complaints in his personnel file, including two substantiated complaints for an unlawful stop-and-frisk. Gansrow is assigned to SRG 4 in Queens.

One of the SRG bike officers who set up the Times Square kettle was Sgt. Matthew Tocco of the Disorder Control Unit. Tocco has amassed 21 CCRB complaints since joining the NYPD in 2006, including allegations of chokeholds, improperly pointing a gun, beating suspects with his nightclub, excessive force, discourtesy, and refusing to provide his badge number. The majority of complaints — 15 of which involve claims of excessive force — were accrued during his time in the West Village’s Sixth Precinct in the 2000s and 2010s. None of the complaints against Tocco were substantiated.

Also supervising the bike officers in Times Square that day was Sgt. Richard Jones from SRG 1, stationed on 42nd Street one and a half a blocks from the Hudson River. Jones, who has had nine CCRB complaints against him (none substantiated) since becoming an officer in 1999, has a history of alleged misconduct at demonstrations. On Dec. 17, 2011, he arrested Michael Premo at an Occupy Wall Street march and charged him with felony assault. In a criminal complaint, Jones claimed that Premo attacked and injured him while resisting arrest. After 14 months, 13 court appearances and four trial dates, a jury acquitted Premo of all charges. He filed a civil suit against Jones and the NYPD over the incident and received a $55,000 settlement. By surrounding the demonstrators and arresting them within seconds of issuing a pre-recorded dispersal order, SRG returned to tactics from the 2004 Republican National Convention that courts later deemed unlawful.

“In RNC cases, we sued them over a bunch of different arrest locations and practices — one of them was a kettle on 16th Street on August 31, 2004, the ‘day of anarchy,’ when the cops did all these pre-emptive arrests,” said Oliver, one of the attorneys involved in the convention litigation. “In Times Square, they did what they did in the Mott Haven kettle in the Bronx, which was to either direct and let protesters go down a certain place where they had a trap set up, with cops on both ends.”

“They need to provide a warning. It’s not sufficient for them to say, ‘OK, everybody disperse,’ and then come and make arrests,” said David Rankin, an attorney who spoke at a Sept. 21 press conference held by the Times Square arrestees.

Long-term consequences

The NYPD’s policing of demonstrations may have long-term consequences for a city struggling to dig its way out of COVID-19’s economic chasm. At least 98 notices of claim have been filed with the New York City comptroller in relation to the SRG-led Bronx mass arrest in June alone, potentially costing city taxpayers millions in legal settlements. Since May 26, the CCRB has received at least 18 complaints against SRG officers. The independent oversight agency is investigating more than 750 complaints related to the protests.

Each passing week seems to bring new instances of hyper-aggressive protest policing by the SRG.

On Sept. 26, SRG officers arrested a dozen demonstrators in a tumultuous scene on a West Village street, with riot and bicycle officers diving in among outdoor restaurant patrons to make arrests. The incident shocked passersby and drew instant criticism from legislators. Brad Hoylman, who represents the neighborhood in the New York State Senate, wrote on Twitter that he had contacted the NYPD for an explanation, labeling that evening’s events a “disturbing escalation of force” that was “unwarranted and unacceptable. On the night of Oct. 5, 24 demonstrators calling for the arrest of a Texas police officer who shot and killed Jonathan Price were arrested and briefly detained by SRG on minor charges — including preventing officers from NYPD’s surveillance specialists in the Technical Assistance Response Unit from filming the protest — in Lower Manhattan. In remarks to the media, Commissioner Shea insulted the protesters and said they were keeping officers away from calls about violent crime — even though the SRG has been ever-present at protests, and shooting incidents citywide have fallen since a midsummer peak. “We don’t need officers pulled away for these, sometimes I don’t know what you call them — peaceful protesters — maybe spoiled brats at this point,” Shea said.

The NYPD and SRG’s rough treatment of demonstrators for the last several months has fueled, rather than tamped down, street protests. Andom Ghebreghiorgis, a Bronx resident who was arrested on June 4 and spoke with Human Rights Watch for its report, said the initial demonstrations swelled “because police brutality protesters were being viciously, viciously attacked from Brooklyn all the way to the Bronx.”

“It has mobilized a lot of people to get out,” he said.

Ali Winston (@awinston) is an investigative reporter on surveillance, privacy and criminal justice.