The largest predictor of police violence in America is not poor training, lack of discipline, or militarization. The largest predictor is simply contact with the police — and the most common contact Americans have with police is traffic stops. There are at least 20 million traffic stops per year in the United States. Racial bias pervades traffic enforcement, enabled by its largely discretionary nature; there are more drivers speeding and violating other traffic laws than police have the capacity to pull over and ticket, so who are police disproportionately targeting? People of color.

Thirty-two-year-old elementary-school lunch supervisor Philando Castille was pulled over 46 times in Minneapolis before being shot and killed by a police officer. Of all of the stops, only six of them were things a police officer would notice from outside a car, such as speeding or having a broken muffler. Twenty-eight year old Sandra Bland was pulled over for failure to signal a lane change by a Texas State Trooper, arrested and later found dead in her jail cell by what the police claims to be a suicide. Her family contests the suicide ruling.

Traffic stops are viewed as an essential tool in the law-enforcement arsenal because officers are constitutionally permitted to search a vehicle during a stop if there is probable cause to believe evidence of a crime exists in the vehicle or if it is reasonably necessary for officer safety. But so often the probable cause appears to be driving while Black; Black Americans are stopped almost 40 percent more frequently than white Americans. The traffic stop frequently serves as pretext for significantly more invasive crime enforcement and is used to permit the police to intrude in the lives of Americans, particularly Black Americans, Indigenous Americans, and other Americans of color.

Last month, New York Attorney General Leticia James recommended removing the NYPD from routine traffic stops in order to reduce police violence. I agree, but let’s not stop at New York City. All New Yorkers deserve better than the status quo. To decrease police contact with citizens — thereby reducing the potential for racist police violence, escalation, and unnecessary interaction with the criminal-justice system — while maintaining road safety, New York can lead the nation by eliminating traffic enforcement from the purview of the police. Instead, we can create a new, non-police (non-weaponized) Traffic Safety Service within the NYS Department of Transportation dedicated to ensuring traffic safety, with anti-racism built into the unit’s DNA. And New Yorkers overwhelmingly support the idea.

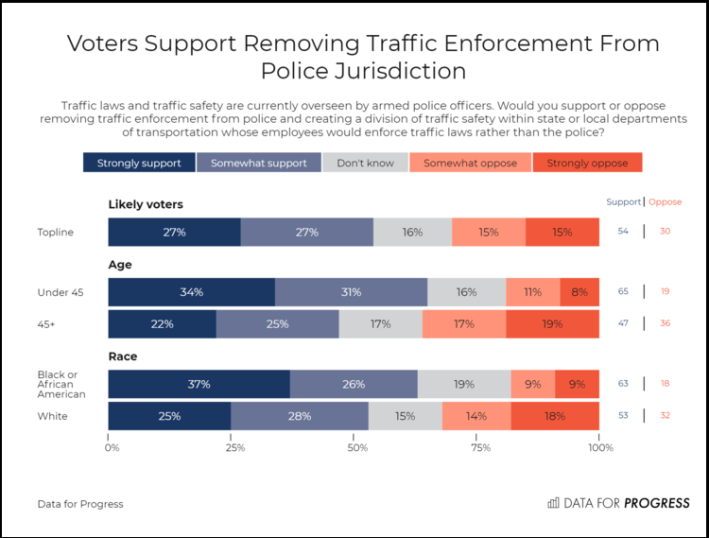

As part of a September survey, Data for Progress tested support among New York likely voters for this proposal. They found that it enjoys widespread support. Overall, voters back it by a 24-percentage-point margin (54 percent support, 30 percent oppose). This proposal is particularly popular with voters under 45, who support it by a 46-point margin (65 percent support, 19 percent oppose). Among voters over 45, it’s supported by an 11-point margin. Both Black and White voters support this proposal by large measures, the former by 45-points (63 percent support, 18 percent oppose) and the latter by 21-points (53 percent support, 32 percent oppose). And in New York City, 70 percent of residents support a Traffic Safety Service, with just 20 percent opposed.

Procedural policies focusing on training, de-escalation, and heightened standards for use of force have value and can reduce police violence, but reforms such as implicit bias training and body cameras have shown limited success. Procedural reforms that work should be pursued, but that ground is well-trod in comparison to the much more cost-effective and easier-to-implement reform: reduce unnecessary contact between police and citizens.

A program such as this is not without precedent. For 60 years, New Zealand maintained a Traffic Safety Service that acted independently of the police. Officers lacked broad arrest authority and served as public-health officials responsible for the administration of traffic-safety laws, just as the Health Department inspects restaurants. Studies showed that by limiting traffic enforcement to the safety service, and accordingly needless contact with police, New Zealand was able to improve societal relations with law enforcement. Specifically, when compared to Australians, drivers were much more likely to respect police in general because of a reduction in negative or potentially biased interactions. Moreover, improving perceptions of police legitimacy can have long-term benefits for compliance with the law in other areas.

With calls to defund the police and to fundamentally improve American policing at the highest levels, removing police from traffic enforcement would radically reduce police contact and improve public safety. Let’s lead the way.