The Regional Plan Association’s new Five-Borough Bikeway report may be the most inspired New York City bike-related document to appear since Trans Alt’s 1993 Bicycle Blueprint.

That Blueprint — a 160-page combined encyclopedia and plan [PDF] — was my and Jon Orcutt’s joint valedictory after our long respective stints as TA’s president and executive director. It was suffused with desire but, in places, skimpy on detail. Perhaps overly mindful of drivers’ chokehold over city transportation, we didn’t include a continuous citywide network of cycle paths and lanes.

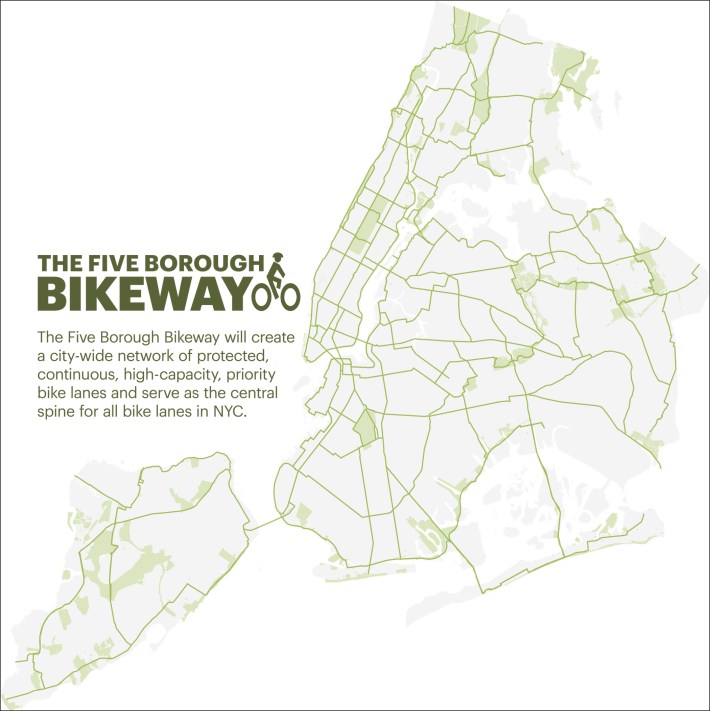

Now, in 2020, the zeitgeist is shifting and RPA is plugged in. (Orcutt, now at Bike New York, advised the RPA team.) The writers have subtitled the report, “Critical infrastructure connecting New York City,” and boy, do they mean it. They’ve sketched an ambitious Five Borough Bikeway and mapped it here.

A hundred or more miles of the network already exist, from the late-nineties (1890s, that is) Ocean Parkway bike path to early 21st-century greenways paralleling the Hudson and Bronx rivers. Most of the mileage would be new, however.

The new bikeway sections would vary from two-way bike tracks (think Prospect Park West or Vernon Boulevard) to dual tracks on either side of busy, two-way arterial roads, to residential “bike boulevards.” The resulting 425-mile high-capacity, “priority” bike lane network would serve as the central spine for hundreds of miles more secondary and tertiary lanes.

RPA’s bikeway map necessarily is a work in progress, since community input and detailed engineering studies will be needed before the shovels can go in. What’s crystal clear is RPA’s conviction that “a mix of scenic greenways, wide boulevards, car-choked commercial streets, and quieter back roads can be adapted and transformed to create the continuous, core bike network that New York City needs.”

Less important than the precise configurations is that the Five Borough Bikeway would be “citywide, continuous, connected, conflict-free, and constructed.” That last word is key. To actually construct the network and the collateral lanes, and to ensure that they’re physically constructed and thus blockage-proofed rather than merely painted, RPA is calling on elected officials not to reform the community board-based veto process so much as circumvent it.

RPA minces no words in pointing out that “community board … members tend to be less representative than the greater community [and] have higher levels of car ownership than the neighborhoods they serve.” As a result, the boards “all too often fight new bike lane projects, [forcing] DOT “to refine projects over months and even years. This leads to fewer projects being built and a general dilution of projects that do make it through,” says the report, “vastly limiting the potential of cycling.”

It’s saying something when the nation’s oldest and most prestigious planning organization — RPA was founded in 1929 and its directors are a Who’s Who of New York City business and intellectual movers and shakers — tells the city’s 59 community planning boards to stop — yes, just stop — obstructing bike lane proposals; and, in effect, signals to 2021 mayoral hopefuls that it’s past time to turn the page on the extreme NIMBYism perpetrated by free-car-storage troglodytes.

Echoing perennial calls from grassroots-level advocates, RPA is telling city government it can no longer afford to ignore cycling’s myriad benefits, not just for individuals but for New York’s civic fabric, urban livability and economic viability. In RPA’s words, these benefits include:

- Reduction in traffic congestion due to cars

- Reduction in air pollution while shrinking NYC’s carbon footprint

- Reduction in intermodal conflict between bikes, cars and pedestrians

- Accommodation for new modes of transport and micro-mobility

Yet, with respect, the full list of cycling’s goods for New Yorkers also includes bicycling’s affordability, speed and convenience; its contribution to individual autonomy, well-being, cognition and health; its capacity to provide thousands of truly artisanal jobs across the five boroughs in maintaining, servicing and selling bicycles; its innumerable synergies that include not just safety-in-numbers (declining individual risks as cycling volumes rise), but a host of other positive feedback loops as cycling becomes normalized; its cross-generational availability and cross-racial appeal; its particular offer to youths of color of the “right to the city,” provided that NYPD is made to cease its racist profiling; and, in what doubtless will be a protracted post-COVID recovery, an alternative to crowded mass transit and externality-spewing cars.

“While fewer than one in ten trips in NYC are made by bike today, there is no reason to think NYC couldn’t be a world-class cycling city, with comparable levels of ridership to Copenhagen or Amsterdam,” the RPA report insists. Toward this end, the report includes brief but pithy sections on almost every subject under the bicycling sun: Closing the gender gap in ridership. Closing the racial and ethnic gap in bike infrastructure. Setting ambitious annual targets and hitting them. Picking low-hanging fruit immediately. Speeding up construction. (And so forth.)

Two areas to which RPA might have given more play are electric-assist cycling and subsidizing bike-sharing and bike-buying. E-bikes are bursting with potential to expand cycling ridership and trip ranges by helping people manage the required physical input and softening the stigma sometimes attached to cycling as low-status drudgery. Subsidizing bike purchases, meanwhile, appears to be gaining footholds in some European cities and countries as a means of erasing financial hurdles to bike ownership and use. Neither receives much attention in the RPA report.

Those omissions should be seen as minor. The report’s ambition, clarity, urgency and provenance make it a landmark. An organization long known primarily (and perhaps unfairly) for grand and sometimes 30,000-foot-level pronouncements has declared that creating a comprehensive five-borough bike lane network constitutes a “critical” priority.

Twenty-seven years ago, Bicycling magazine Publisher-Editor J.C. McCullagh proclaimed in his foreword to Trans Alt’s Bicycle Blueprint that “The bicycle can save New York.” RPA’s vision of its Five Borough Bikeway as “critical infrastructure … that will reconnect workers to jobs, goods to customers, neighborhoods to other neighborhoods, and friends and family to each other,” while not as pithy, has the same intent: to lift up all who live here and revitalize our great city.