Mayor de Blasio said this week that he is having "active conversations" about about relieving the NYPD of its outsized role — and statistically documented racial bias — in traffic enforcement and public space management.

The mayoral admission comes as the chorus calling for reining in the NYPD grows louder in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis — a symphony of voices that has not subsided even as the mayor announced reforms such as shifting some NYPD funds to youth programs and also removing the NYPD's oversight of street vendors.

Advocates want more, specifically getting the NYPD out of public space. On Thursday, Mark Winston Griffith and Danny Harris, the executive directors of the Brooklyn Movement Center and Transportation Alternatives, wrote in Gotham Gazette that having the NYPD involved in traffic enforcement and public space management amounts to "spending so much money on practices that harm people of color" because of the police department's racially biased enforcement.

The same day, the mayor said he was sensitive to the call.

"I think there's other areas [beyond the change in vending enforcement] where civilian efforts would be better," he said. "We made that decision on social distancing as well. We're going to keep looking at that. [But] traffic enforcement is something that we all need to keep this city safe, to keep this city moving."

So for now, cops remain in traffic enforcement — despite the fact that traffic stops are the most likely way that cops interact with the public, according to the Department of Justice. And, as Vice recently reported, cops are far more likely to search the car of a person of color than a white person. Officer discretion has bocame officer discrimination, writer Aaron Gordon concluded.

De Blasio did say he was sensitive to ensuring that communities of color are treated fairly. The NYPD's record on that is poor. Statistics show that 99 percent of "illegal pedestrian crossing" tickets went to blacks and Hispanics in the first quarter of this year, up from 89 percent in 2019. And when cops were still doing social distancing enforcement, 90 percent of the people arrested were black or Hispanic.

SIDEBAR: THE NYPD IS A TERRIBLE VISION ZERO PARTNER — A TIMELINE

And that's on top of longstanding patterns of systemic racism. The stop-and-frisk policy of then-Mayor Bloomberg meant that black and Latino people were nine times more likely to be stopped by police than whites, even though white people were twice as likely to be found with a gun, Griffith and Harris pointed out. And cops write far more tickets to black and brown cyclists for riding on the sidewalk than they do to whites.

And obviously the NYPD killings of Sean Bell and Eric Garner would not have happened if civilians were enforcing basic rules governing public space.

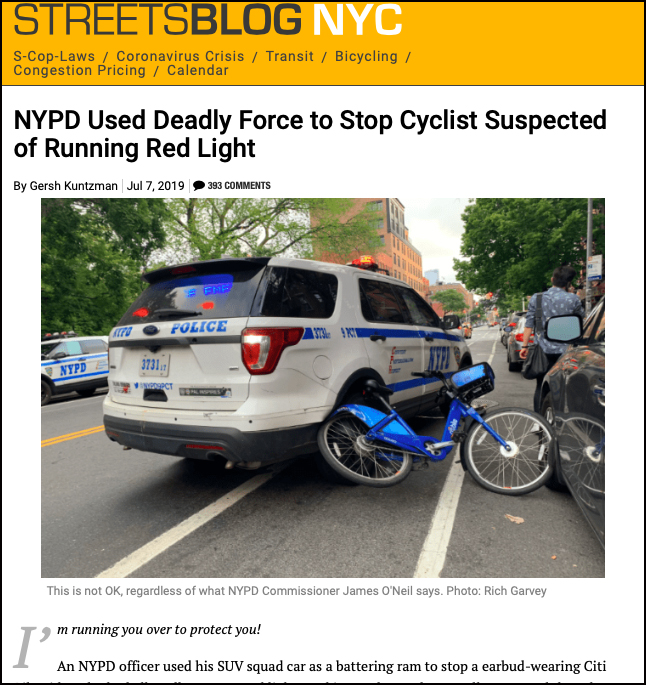

And beyond racism is simple disrespect for some road users. Would a DOT employee tell a cyclist to "go back" where they came from, as an NYPD officer did last year? Would a civilian use a car as a battering ram against a defenseless bike rider, as another cop did last year?

So why not, the mayor was asked on Thursday, move all such enforcement into a possibly more egalitarian agency, such as the Department of Transportation?

"I won't accept any bias or disparity," the mayor said. "Structural racism has got to be a thing of the past. It's been corrosive. So I think there is a different question here about how you weed out racism and bias and disparity versus also considering how you get the job done on these issues that matter so deeply. We have to do both at once. So we have to protect people's lives. We have to make sure that people are safe on the road. We have to make sure that any agency that takes on any mission feels able to do it effectively.

"I don't think it is as simple an equation as what you are putting forward," the mayor added. "So, are we going to look at everything? Yes. ... But what I hear in communities all over the city is people want to be safe and they want an end to bias and discrimination and disparity. They want both, they need both. We have to figure out what gets us to both. And that's what these conversations in the next two weeks are going to be all about."

And we certainly don’t need NYPD doing traffic enforcement, in our schools, or engaging with those living with mental illness. Hope this is the start of many changes. https://t.co/67yCopib2L

— Carlina Rivera (@CarlinaRivera) June 12, 2020

The reference to "two weeks" is to the current budget negotiations. Activists — and some council members, according to this tracker — have demanded a "defund the NYPD" strategy that would cut the agency's annual $6-billion budget by $1 billion. Comptroller Scott Stringer has also set $1 billion as a benchmark — but he would spread the cuts over four years (though sources said Stringer now realizes his original proposal was too low).

[Update: Over the weekend, Council Speaker Corey Johnson issued a statement setting $1 billion as the benchmark for cuts: "We have identified savings that would cut over $1 billion, including reducing uniform headcount through attrition, cutting overtime, shifting responsibilities away from the NYPD, finding efficiencies and savings in OTPS spending, and lowering associated fringe expenses. As we do this, we must prioritize the most impacted communities and hear their demands and needs across all areas during this budget process. This should be a deliberative and good faith discussion of the best path forward for New York City. Our budget must reflect the reality that policing needs fundamental reform." City Hall responded with a statement from mayoral spokeswoman Freddi Goldstein: "The Mayor has said we're committed to reprioritizing funding and looking for savings, but he does not believe a $1-billion cut is the way to maintain safety."]

Whatever the number, a strategy to reduce policing must involve getting the NYPD out of public space management, which has been a key role of its Transportation Bureau, whose transportation portfolio is broad — encompassing traffic management, design and enforcement, all three of which should be entirely in DOT's column. The bureau's $225-million budget is basically one-quarter of the DOT's entire budget.

In an interview with Streetsblog earlier this week, Department of Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said she believes that the NYPD has been a good "Vision Zero partner" of the DOT, despite videos that emerged this month and last of police brutalizing cyclists, running squad cars into protesters and using their own bikes as weapons against protesters.

Advocates say the recent bloodshed by police is the last sip of a relationship that has long been sour.

"From the onset of Vision Zero, we have been critical of the outsized role NYPD has played in it," said Marco Conner DiAquoi of Transportation Alternatives. "The main problem is that the NYPD has a mandate to use force — so force is what you get."

And that force is disproportionately leveled against communities of color — which, in the current debate, has broadened the very definition of "safe streets" beyond design that reduces the number of fatalities or injuries, but to include whether black Americans, indigenous people or people of color are safe to walk down any sidewalk in town without fear of being brutalized by an agent of the state.

But even on the most neutral issue of street safety across all communities, TransAlt and other groups have long wanted the NYPD to be holstered in favor of design that reduces the need for any policing.

At @TransAlt, we support #BlackLivesMatter and the movement to #DefundNYPD. What does this mean in relation to our advocacy? For our part, we believe it is time to remove NYPD from traffic enforcement. https://t.co/AaejDfn80q

— Transportation Alternatives *Vote on Sammy's Law* (@TransAlt) June 12, 2020

"If you design streets correctly, drivers can't speed, so that reduces the need for enforcement, which disproportionately endangers people of color," Conner DiAquoi said. "If you design streets that create space for deliveries, that decreases the likelihood of double-parking, which again reduces the need for enforcement."

TransAlt and others have also long been critical of how the NYPD does crash investigations — with street safety expert Charles Komanoff recently pointing out the "food here is terrible — yeah, and such small portions" problem with the NYPD's Crash Investigations Squad: it's woefully understaffed, and doesn't do a complete job of holding killer drivers accountable.

Komanoff made his anti-NYPD position clear at last year's Vision Zero Cities conference when he was participating in a panel on congestion pricing. Spotting Trottenberg in the back of the room, he went off topic, calling her out for continuing to work with an agency that is not a good partner for street safety or design. Komanoff's comments were not caught on video, but Trottenberg's were. She defended the NYPD for its "evolving" culture — but at that time, she was reflecting mostly on how the agency treats cyclists, which remains only a portion of the agency's problem:

Polly Trottenberg crashes the panel to respond to commentary from @Komanoff regarding the current administration.

— Transportation Alternatives *Vote on Sammy's Law* (@TransAlt) October 10, 2019

We can all agree that more work needs to be done to win safe streets. How we get there — and what mayor leads the way — remains up for debate. #VisionZeroCities pic.twitter.com/c76r91wa6U

Conner D'Aquoi admitted that NYPD will always have some role in punishing reckless drivers "because of their connection to ability to arrest people and present evidence to the DA," but added he didn't know of "a single member of Families for Safe Streets [a group comprised of victims of traffic violence] who has not had a terrible experience because of the NYPD, whether it is their victim-blaming or their outright refusal to investigate crashes." (The cases of Bernadette Karna and Dulcie Canton speak volumes about a broken police culture. The cops' own reckless driving, the fact that a majority live in the suburbs, and the fact that they some hold white supremacist views, explains a lot, too)

The protests stemming from the police killing of George Floyd have added a new intensity to calls for getting police out of public space enforcement — and the renewed focus has revealed continued cracks in the NYPD's attitude.

Council Member @cmenchaca got @NYCMayor’s NYPD to admit they invited ICE / HSI into their precincts at a City Council hearing earlier this week.@bradlander, @JumaaneWilliams, @AdrienneEAdams have been asking City Hall tough questions about NYPD + ICE collaboration. Keep it up! pic.twitter.com/9Df5L8rv2u

— solecito 🇲🇽 (@conelsolecito) June 10, 2020

At a hearing last week, Council Member Carlos Menchaca questioned NYPD officials about why they allowed federal agents, including ICE officers, to provide security at station houses during the height of the protests. The answer from Deputy Commissioner Ben Tucker was very revealing: He said the federal agents freed up NYPD officers so they could return "to the front lines."

Such language, Conner D'Aquoi said, reveals a lot about how the NYPD sees public space.