City & State NY is hosting a full day New York in Transit summit on Jan. 30 at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. This summit will bring together experts to assess the current state of New York’s transportation systems, break down recent legislative actions, and look towards the future of all things coming and going in New York. Join Keynote Speaker Polly Trottenberg, commissioner of the NYC Department of Transportation, along with agency leaders, elected officials, and advocates. Use the code STREETSBLOG for a 25-percent discount when you RSVP here!

A judge's decision last month to throw out a city plan to cap the empty cruising time of ride-hail cabs could be a blessing in disguise that will force officials to come up with a better way to reduce gridlock caused by app-based cab giants, according to one transportation expert.

Yes, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Lyle Frank's ruling means that Uber, Lyft and other ride-share companies won't have to cut their time without passengers from 41 percent to 31 percent — but it could be easier for the city to simply charge the app-based cab companies for the time they drive around empty.

"A charge on idle time is bound to be more effective than a cap in combating Manhattan gridlock, as well as fairer to riders,” said Charles Komanoff, the mobility and cab expert who is reportedly working on a study on the issue for Council Speaker Corey Johnson.

Komanoff said that essentially taxing a bad practice will be more effective than seeking to eliminate it, much as governments have dealt with cigarettes (through high taxes), and traffic (through tolls or congestion pricing).

"As a rule, pricing is superior to caps, period," said Komanoff, adding that the cap tossed aside by Justice Lyle was "convoluted" and "indirect" since it would have been on a percentage of time spent idling, not on the actual number of hours.

If the companies violated the restrictions, which were supposed to take effect next month, the city would have been able impose harsh cash penalties — up to nearly $1 million each month — or even yank their operating licenses from them, Deputy Mayor for Operations Laura Anglin said last year when the plan was announced.

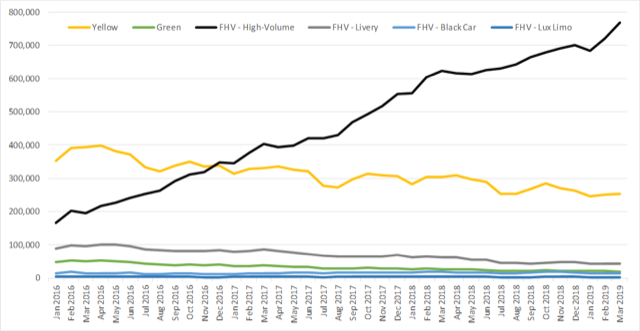

The city came up with the cap in order to reduce the number of cabs clogging Manhattan streets — officials said the 86,000 app-dispatched vehicles comprise about 30 percent of traffic during peak periods in Manhattan below 60th Street, and a large chunk of that traffic stems from drivers waiting passenger-less in the borough's central zone.

Officials claimed the cruising cap would increase speeds during the evening rush hour by up to 10 percent — a projection that Komanoff once called a pipe dream, previously telling Streetsblog it would likely only increase them by 2.5 percent.

The city is considering appealing Lyle's ruling to reduce what it says is 40 percent of vehicles driving around empty, clogging streets, and creating “significant environmental problems," as well as making it a "headache for New Yorkers to get around the city in a timely fashion,” according to a spokeswoman for City Hall.

A spokesman for Uber said the company welcomes other policies that would reduce congestion.

"We are pleased that the court recognized that Mayor de Blasio’s cruising cap is arbitrary," said Harry Hartfield. "Uber remains committed to fighting for driver flexibility in the face of politically motivated regulations and to standing up for policies that actually combat congestion.”