With 13 months left before the potential debut of America's first-ever congestion pricing plan, it's time to ask the key question facing the program: Is New York City prepared to make a congestion toll work? Or are we totally boned?

We're totally boned, say some experts. Let's see why:

Transit improvements must come first

European cities that instituted congestion pricing demonstrated that it's hugely important to expand public transit options before tolling starts. That's one reason why the Regional Plan Association made "Implement transit and bicycle improvements prior to starting congestion pricing" its number one recommendation in a report literally titled "Congestion Pricing In NYC: Getting It Right."

So on that subject, should we be panicking right now?

"There's a risk of that we're setting ourselves up to totally mess this up," Ben Kabak, the publisher of Second Avenue Sagas, told Streetsblog. "Based on the [deliberate] way the MTA plans work assignments and increases capacity, we're running out of time."

The MTA hasn't released plans that suggest increased bus service is on its way, at least not on the scale of London's pre-congestion pricing: a 17-percent increase in bus service. That kind of investment was included in New York's failed 2008 congestion pricing proposal, but not this time.

"That plan would have been paired with hundreds of millions of dollars for bus routes serving the outer boroughs," said Ben Fried, the communications director at the TransitCenter. "The governor should be thinking about how to do something similar."

Nick Sifuentes, the executive director at the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, said the advantage of adding extra bus service was obvious: the humble bus is incredibly versatile.

"There's certainly a lot that you can do with frequency improvements and street priority to make bus service much more accommodating of an influx of new riders," Sifuentes said. "You can increase your frequency and make the bus work better [with dedicated bus lanes, for example]. You can buy the rolling stock, which a lot less expensive and gets delivered faster than a new train car, you do the work of putting the surface priority down and boom, there you go."

But the MTA's current plan seems to be that it doesn't need a plan. Indeed, CEO and Chairman Pat Foye recently suggested that New York doesn't need to increase capacity in the same way that European cities did.

"London and Stockholm and Gothenburg didn't have the commuter rail systems we have here in terms of Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North, bringing 80 million passengers" to New York, Foye said, referring to the railroads' annual ridership numbers into the city. The MTA's head honcho added that "there is latent unused capacity in subways and buses," given that currently only 75 percent of trips into the central business district are done by mass transit.

"That means that we will clearly be able to handle those who leave their cars and come to mass transit," he said at a recent legislative hearing.

Transit advocates were unconvinced, to say the least.

"That's an absurd statement," Sifuentes said. "One, our commuter rail systems are operating pretty close to capacity. Until we have main line expansion and East Side Access done, and we have more rolling stock, they're not really able to take on massive amounts of new people."

Foye's answer that the commuter rail has excess capacity is a 180 from statements made by previous MTA Chairman Joe Lhota and by the LIRR itself this year. In 2018, Lhota dismissed a report by Comptroller Scott Stringer that claimed the MTA had enough excess capacity to offer $2.75 fares for New Yorkers doing intra-city travel on the LIRR and Metro-North.

In March 2019, LIRR President Phil Eng said that the commuter railroad was operating at capacity. New capacity, in the form of next-generation train cars that were supposed to be in service by 2022, won't be finished until 2024.

And even if there is the capacity that Foye cited, the fares are too damn high, Sifuentues said.

"If you're trying to take the LIRR in Queens into the city, you're still paying six to eight bucks to do that every single day," he said. "And that's not affordable compared to $2.75."

"If we're going to say that commuter rail is something that people are going to use as this alternative, especially people who live in the city, then we need to be looking at the Freedom Ticket much more seriously, too," Sifuentues added, referring to discounted one-way fares between Atlantic Terminal and certain LIRR stations in Queens and Brooklyn.

Kabak said he found Foye's answer worrying and "wrong," and said that without increasing service the MTA is telling city residents to just deal with crowded rush hour subways and infrequent off-peak bus service.

"If everything is a mess on Day 1 of congestion pricing, the MTA isn't going to be able to add enough buses on Day 2 to make up for it," Kabak said.

MTA spokesperson Amanda Kwan said that the MTA was taking congestion pricing into account in its bus network redesigns. But in the Bronx, the bus network redesign was praised by advocates for untangling the unwieldy borough's routes, but it was criticized for not including investment to ensure service every three to five minute on crucial routes during peak hours.

The city has a role

Crowded buses are workable if they get where they're going quickly thanks to dedicated lane, or the city creates alternatives for non-drivers, such as more bike lanes.

To that end, Bike New York and Transportation Alternatives put out a wish list this summer pointing to gaps that the DOT can fill in the protected bike lane network inside the Central Business District, plus improvements on key feeder routes, such as Flatbush Avenue from the Manhattan Bridge to Empire Boulevard, Northern Boulevard between the Grand Central Parkway and Queens Plaza, and Skillman Avenue to the Pulaski Bridge.

And when it comes to potential bus improvements, Fried said the city should prioritize Downtown Brooklyn (to unsnarl Jay, Adams and Livingston streets so buses can get through traffic unimpeded), the Queensboro Bridge (with new eastbound bus lanes so Queens-bound express buses can get out of Manhattan), and the Bronx (where crosstown lanes "would really make the borough’s transit network hum," Fried said).

Oh and one more thing: More busways please! Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer recently endorsed a Busway on 181st Street, which could make it easier to institute in the future, but almost every clogged community wants its own version of the Miracle on 14th Street.

For now, thought, the city's plan is unknown. The mayor himself channeled whatever Brooklyn is inside him and told long-suffering bus riders to "Wait 'til next year" before he unveils new busway-style corridors.

Traffic problems on the mobility review board

The city has also has a role in creating the Traffic Mobility Review Board, a six-member panel that is still entirely unstaffed even though its recommendations for how congestion pricing will be implemented can be issued after Nov. 15, 2020 — less than a year away.

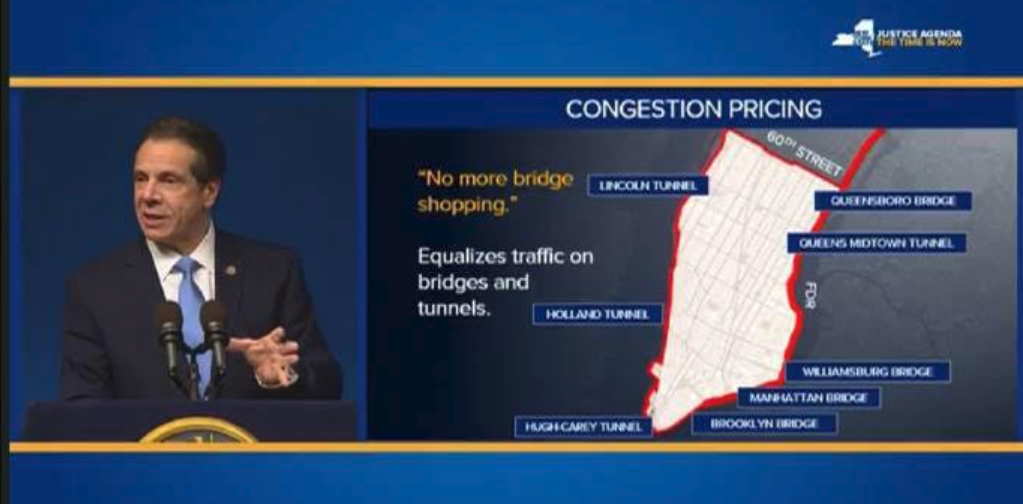

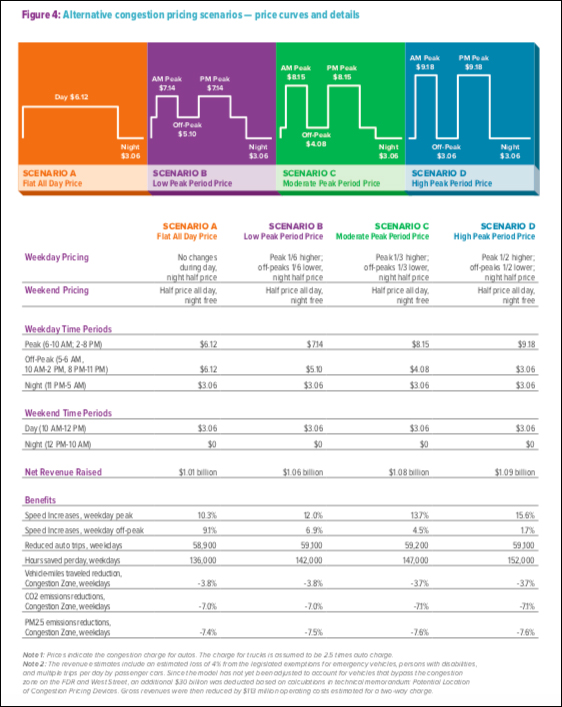

The board will analyze the nuts and bolts of congestion pricing, such as how much the tolls will even cost, if the toll will be one- or two-way, and whether the fee will be flat or if it will change hour by hour (or even minute by minute). The only legal requirement is that the tolls must raise $1 billion per year — enough to generate $15 billion in bonds to pay for the historic 2020-2024 capital plan.

"It's absolutely fair for us to be asking 'What's going on with the TMRB?'" Sifuentes. "It isn't seated yet, and it should be following the open meetings law."

The tolling to enter Manhattan below 61st Street can legally start on Jan. 1, 2021, so time's a-wastin'. The MTA did hire a company to build the tolling infrastructure itself, but Kate Slevin, a senior vice president at the Regional Plan Association, urged the agency to immediately focus on appointing members to the TMRB.

Appointing the board sooner rather than later provides "a benefit as it starts to try to explain the various tradeoffs that you might get from different toll levels," Slevin said.

As the RPA showed in its congestion pricing report, there are a number of ways the congestion pricing toll can be instituted in order to raise the legally-mandated $1 billion, including the best option: a $9.18 peak-hours toll to get into and out of the CBD.

There are other options (see chart), but the most important thing is for the TMRB to get down to work, so drivers won't feel blindsided, stakeholders can get their say, flaws can be fleshed out, and people can plan ahead.

"There is an important oversight and independent role that that body will play in the public dialogue," she said.

For now, the mayor is not ready to announce his one appointee to the TMRB, but is discussing membership with qualified candidates," City Hall spokesperson William Baskin-Gerwitz said.

By not taking the lead on the TMRB, the de Blasio administration risks disaster, advocates believe.

"The thing that keeps me up at night is a badly botched rollout of congestion pricing," said Sifuentes. "In this case, we are giving people something, which is better transit. But the fee is coming in some cases before the better transit."