Mayor de Blasio's $58-million “Green Wave” and the City Council’s “Streets Master Plan” — enacted as cycling deaths have more than doubled this year — promise to add miles of protected bike lanes to make streets safer. Yet, for cycling to become a truly safe mode of transportation, the city must implement the new infrastructure in a way that makes riding a bike as convenient, connected, and “seamless” as driving a vehicle.

In this, New York should take a page from the most bike-friendly cities, which design their streets as part of the urban fabric, not simply as transit corridors. In particular, Copenhagen, which designs its streets for a thriving cycling culture and as an overall safe system for people “getting about and getting on,” provides lessons for our own transportation planners.

Copenhagen and some other dense cities build their streets based on observing how people move and behave — designing around their needs and making cycling safe and convenient. With streets that welcome people out of their cars, Copenhagen boasts an entrenched culture of walking and cycling: A staggering 41 percent of adults ride bikes to work or school; 25 percent of school children bike and 40 percent walk; and 52 percent of bike commuters are women.

Today cycling is integral to Danish culture, but it wasn’t always thus. Pushed by the 1970s oil shocks, Copenhagen’s cycling culture arose during the past 50 years because the city put in place a strategic, people-centered approach to reclaiming road space, by responding to data about how human beings wanted to move about the city.

Now, 78 percent of Copenhageners report that they cycle because it is the fastest, easiest, or most convenient way to get around (as opposed to 7 percent who say that they ride because it’s eco-friendly). Riding a bike is no more a part of a Dane’s DNA than it is of a New Yorker’s; people ride because it is easy, direct, and intuitive — and they feel safe.

Danish planners observed that biking in city traffic can be challenging and dangerous for cyclists, who feel vulnerable surrounded by bigger, heavier, and faster motor vehicles. So they designed bike lanes to provide safety and comfort and make cycling much easier and more predictable — and made the bike network simple and easy to understand. Cyclists have their own space, yet remain integrated with the flow of the street and the other users.

How does it work? The “Copenhagen model” puts a dedicated bike lane between the sidewalk and the vehicle lanes. The bike lane is separated from the pedestrians with a low, three-inch curb, enough to make the zones distinct. More important, a second curb of the same size separates cyclists from motorists.

Each mode of traffic has its own surface, providing order because everyone knows their place. In the same way that motorists know not to drive on the sidewalk, they know not to drive on the bike lanes, either — and cyclists, for their part, know not to ride on the sidewalk. With such clarity, users avoid most basic conflicts. Moreover, the convenient location of the bike lane next to the sidewalk gives cyclists immediate access to the system — an “ease of entry” that encourages cycling.

In Copenhagen, planners maintain consistency in the relationship among the sidewalk, bike lane, and street. The bike lanes are all one-way, in the same direction as the vehicle traffic — so, intuitively, cyclists move in the same direction as cars. Even more so, they aren’t threatened by oncoming traffic and avoid potentially fatal collisions. Because the bike lanes are next to the sidewalk, cyclists only have cars on one side, unlike in most other cities, where they may face vehicle traffic on both sides. This makes cycling feel much easier, safer and less stressful.

Most cities let motorists park next to the curb and then put the bike lane alongside the parking lane, which is complicated and stressful for both kinds of users. In Copenhagen, parked cars also act as a protective barrier between the bike lane and the traffic lane. (Editors note: Streetsblog works to eliminate free parking and is not convinced that parking "protected" bike lanes are the best way to go.)

In this way, the Copenhagen model benefits motorists, too. City parking is already one of the most stressful aspects of driving — without the complication of dealing with cyclists. If motorists must cross over a bike lane in order to park, they must maneuver with care, and often have limited visibility while reversing. They must look out for oncoming cyclists, which can be difficult and hold up traffic, and is especially dangerous for cyclists. Once parked, motorists also must ensure that they do not "door" cyclists while exiting. By keeping the business of parking cars outside of the business of cycling, the model is a “win-win.”

The Copenhagen model shows that, while more funding for cycling infrastructure in New York City is crucial, investments must be informed by human behavior — by men and women, young and old, walking and biking in the city today.

The Department of Transportation produces a regular bicycle count, a quantitative report that focuses on the East River bridges and Midtown — not on the city’s diverse neighborhoods or on qualitative data about travel choices. Observation and people-centered data could help the agency avoid investing in safety measures that don’t make people feel safer. Surveys, engagement, and pilots that let people experience something new can provide insight on where and how to develop new bike lanes and convert painted lanes to protected ones.

New York constantly changes (will we have scooters? Will firms start making package deliveries by bike? What's the next micromobility invention?) even as our need to interact socially at school, play, work, or civic demonstrations persists. The regular, consistent, anonymous observation of how people use streets — where they move, park their bikes, feel safe — can inform how to create an adaptable, human-powered mobility network, catalyzing a “Green Wave” that invites New Yorkers back onto their bikes and makes streets safer for all.

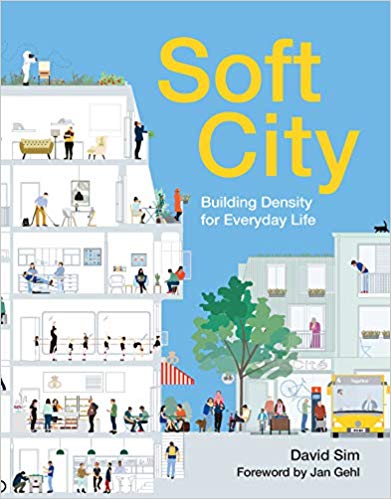

Julia Day (@Jddnyc) is a team lead and David Sim (@DavidSimatGehl) is creative director at Gehl, an architectural firm focused on people-centered urban design with studios in Copenhagen, New York, and San Francisco. Sim’s new book on designing better cities using low-tech, low-cost, human-centered solutions is “Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life” (Island Press).