Congestion pricing passed the state legislature on Monday morning with minimal exemptions. Don't count on it staying that way.

Lawmakers did make history when they mustered the votes to toll drivers who enter Manhattan below 61st Street — a plan decades in the making. But they left the key details to a newly created "Traffic Mobility Review Board," which will come up with the cost of the tolls, who will pay, and when the system will be implemented.

The legislature mandated a target — enough revenue to support $15 billion in bonds for transit improvements — but specified little else [PDF]. So apres le budget, le deluge: After hearing from the public, the new panel will recommend tolling fees and exemptions to the MTA board, with just 30 days of public review before the program goes into effect in late 2020.

The forthcoming flood of exemptions, set to be considered by the toll-setting panel through an extensive public process, could be quite substantial.

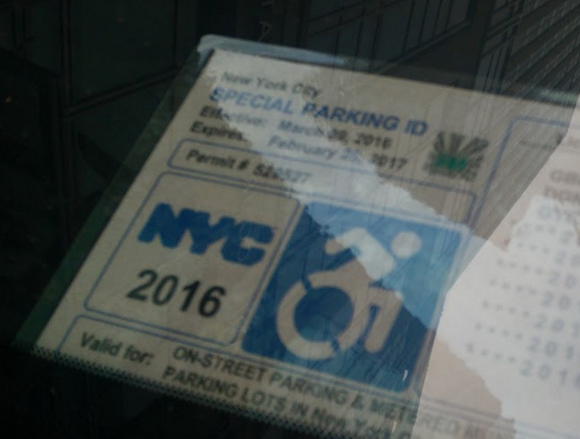

More than a half-dozen possible exemptions circulated in the weeks leading up to Monday morning's budget vote. In the end, the list was whittled down to just three vague and still undefined exemptions: one for "authorized emergency vehicle[s]" as defined by the state traffic law; one for "qualifying vehicles transporting a person with disabilities," and a tax credit for Manhattanites living below 61st Street and making less than $60,001 per year (they would pay the congestion toll, but get it back from the state when they file their taxes).

Those three exemptions — and how they're defined — will set the tone for the toll-setting panel — and shape the expectations of the public. The state definition of "authorized emergency vehicle" could wind up including the private cars of placard-holding first responders commuting to work, for example. And the tax rebate, which would come out of the state's general fund and therefore does not impact the money raised for transit, gives the board a way to exempt drivers from the tolls isolated from the bill's revenue target. The panel will also consider credits for drivers who get to the congestion zone after paying a toll to use one of the other state-owned bridges and tunnels.

Legislators are already referring constituents to the toll-setting process as a way to defend their votes in favor of congestion pricing. Queens State Senator James Sanders Jr., for example, listed the program in the "what needs work" section of his post-budget email newsletter — implicitly passing the buck to the MTA and its new toll-setting panel.

"More work needs to be done to lessen the impact on Queens' motorists commuting into Manhattan," Sanders wrote, ignoring the fact that only 3.1 percent of his constituents commute regularly into the congestion pricing zone.

Further adding to the noise: the Trucking Association of New York, which counts FedEx and UPS among its members. The organization's president told Bloomberg News that all commercial vehicles should be exempt.

Advocates and elected officials, however, hope that the toll-setting panel will be able to act above the influence of specific interest groups.

The panel's members "must have experience in ... public finance; transportation; mass transit; or management," according the bill, which legislators and advocates believe will safeguard the program's effectiveness in both reducing congestion and raising revenue.

“The way we’ve designed it, there won’t be a battle [over carveouts]," Assembly Member Amy Paulin pledged to Streetsblog on Tuesday. "There’s going to be a professional group … an expert panel, representative geographically of the region, and they will make a professional judgment so that we balance the congestion concerns in the center of Manhattan, as well as raising enough revenue."

Paulin said that she and her Assembly colleagues had hoped specific exemptions would be detailed, but the Senate put the kibosh on them. The bridges and tunnels were ultimately left out after Governor Cuomo mocked them on the radio last week, newly minted MTA Chairman Pat Foye told reporters on Monday.

The panel's mandate "means we’re going to have people who are paying attention to what the real needs are, and not the perceived needs, in looking at exemptions," said Tri-State Transportation Campaign Executive Director Nick Sifuentes.

Also on its agenda: Whether drivers will be charged for driving entirely within the congestion zone.

"These people are going to have to figure out how to get to their revenue target," Sifuentes said. "Better to give them as much of a blank slate as possible to work with."

The carveout for low-income Manhattanites, meanwhile, was the brainchild of the legislature's Manhattan delegation, according State Senator Brad Hoylman, whose district encompasses a big chunk of the tolling zone. In an interview, Hoylman assured Streetsblog he would fight to make sure carveouts don't adversely impact the program's effectiveness, but he defended exempting low-income Manhattanites.

"The charge should be viewed as a progressive one, based on the ability of people to pay — especially as it relates to low-income people," he said. "People who are on lower incomes — that has to be a consideration by the commission."

His colleague Jessica Ramos, of Jackson Heights, Queens, is taking a harder line.

"I consistently have fought for as few exemptions as possible," Ramos told Streetsblog. "We need to make the revenue generated by congestion pricing count and we need to ensure that we’re really aiming to reduce congestion."

The debate over that debate comes as a new poll suggests that city residents are unsure about whether congestion pricing will even work.

Voters polled over the weekend by Quinnipiac University oppose congestion pricing by a 54-41 percent margin. And 52 percent say they don't think it will be effective in reducing traffic. Forty percent believe it will, according to the survey, which was released today.

In cities where congestion pricing has already been implemented, its poll numbers increased only after it went into effect.