With Albany set to approve congestion pricing, the talk has turned to carveouts — discounts or exemptions for supposed hardship cases. And boy, lots of categories are being floated. Excluding total non-starters like exemptions for Manhattan residents (or residents of all five boroughs!), I count five:

- exemptions for tolls paid on "upstream" bridges like the Henry Hudson, the Triborough, and even the George Washington and Tappan Zee

- exemptions for low-income car owners

- exemptions for “essential” city workers' trips in private cars (NYPD and FDNY vehicles are already presumed exempt)

- exemptions for vehicle trips to medical/health facilities

- exemptions for vehicle trips by people with disabilities.

Almost everyone feels entitled to a carveout, but carveouts are an awful idea. As sure as there’s placard abuse, there will be carveout abuse.

“Any carveout can be exploited or widened,” Ben Kabak (@2AvSagas) pointed out on Twitter this week. Exempt or discounted E-ZPasses will be shared with family and friends. Drivers who didn’t qualify will overwhelm the toll administrators with spurious explanations. The system will be gamed.

Administering the carveouts will be costly. New bureaucracies, perhaps one for each category, must be created, staffed, monitored, investigated, and so on. Goodbye to another chunk of the transit-earmarked revenue that advocates fought so hard for and legislators signed off on.

There’s loss of trust, too. Congestion pricing, a brand-new thing on these shores, rests on the principle that every vehicle contributing to the slowing of traffic should pay a charge to mitigate said traffic. Handing out exemptions is bound to undermine this logic, breeding resentment and further eroding compliance.

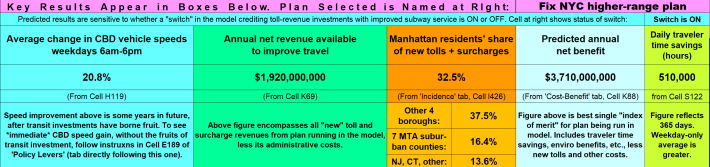

Now let’s look at the numbers. No one knows how many vehicle trips into the congestion zone might be ruled exempt, so I constructed a hypothetical: I decreed that 10 percent of all auto trips into the Manhattan central business district will be toll-free. The results are alarming, as you can see by comparing the BTA’s summary dashboard for congestion pricing with a straight-up version of Fix NYC, with no carveouts:

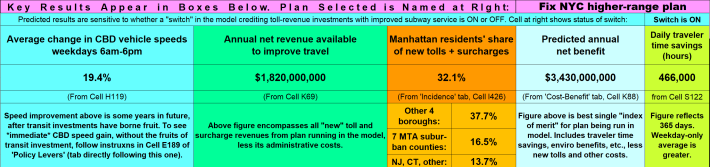

And here's the same plan with carveouts covering 10 percent of eligible trips:

Here are the key differences:

- Net annual revenues that could be invested in better transit shrink by $100 million a year ($1.82 billion vs. $1.92 billion), a difference that means $1.5 billion less for capital spending. A conservative estimate of the impact that doesn’t take credit for higher farebox revenues, $80 million a year, could still bond $1.2 billion, enough to outfit an entire subway line with modern signals that cut 20 percent from the duration of a typical subway trip;

- Average driver speeds in the CBD rise only 19.4 percent instead of 20.8 percent if there are carveouts. So the 10 percent carveout shrinks driver travel-time savings from congestion pricing by 7 percent.

- All travelers — drivers, truckers, straphangers, bus riders and taxi and Uber/Lyft users — give up 44,000 hours a day of time savings. Over the course of a full year, that’s 16 million saved hours stolen from commuters to service carveouts.

- City residents, workers and visitors lose nearly $300 million dollars a year ($3.43 billion vs. $3.71 billion) in congestion pricing’s promised net benefits of saved time, improved health and fewer deadly crashes.

What about the carveout claimants? Viewed in isolation, they have a point. But transportation in coveted and crowded Manhattan is more than a collection of separate trips, it’s an interactive ecosystem in which each trip affects hundreds of others. As I wrote here a year ago, “With the exception of overnight hours, each minute that a vehicle is snaking through the Manhattan core is prolonging similar vehicle trips by a total of 2-2½ minutes. In effect, ‘my’ vehicle’s occupation of Manhattan street space acts as a force multiplier of lost time for other vehicles on Manhattan streets.”

In this light, granting much weight to demands for carveouts is too great a stretch, save for people with disabilities. But even there, subsidizing ride-app services like Uber, as congestion pricing grass-roots campaigner Alex Matthiessen suggests, seems more proportionate and equitable than exempting a license plate or E-ZPass. (This approach can also help smooth the coming shake-out in the app-based vehicle sector if, as I have urged, congestion fees for Uber and Lyft are rationalized with time-based surcharges that account for “trawling” as well as passenger time in the Manhattan taxi zone.)

The lesson is clear: carveouts, like most perks, are not a victimless privilege. The impacts may seem diffuse, but they accumulate quickly. If not tightly contained, carveouts will be a direct attack not just on congestion pricing’s ethos but on its benefits as well.

Methodology: The first dashboard is taken directly from the BTA spreadsheet (downloadable Excel file), running the “Fix NYC Higher-Range Plan” (you can switch scenarios in the Results tab). The second dashboard modifies that scenario by using the BTA's new "Carveout," switch, which is item #14 in the spreadsheet's Policy Levers tab. You'll do that by changing the value of Cell G85 in that tab from its default value of 0%, to 10%. You'll also reduce the current values in Cells G192 and G195 in the Policy Levers tab by $80 million to reflect the “immediate” reduction of that amount in annual congestion revenues that results from the first set of changes.

This revised version fixes a mistake in Komanoff's BTA spreadsheet that caused the post to overstate the impacts of carveouts by a factor of two. That mistake has now been fixed. We apologize for the error in the original post.