The MTA needs a lot of money to fix the subway system. More and more, Governor Cuomo and state legislators appear willing to let it starve.

On Wednesday, the MTA board finally plans to vote on widely disliked but sorely needed increases in fares and tolls simply to avoid going into the red this year. But larger questions loom, including whether lawmakers have any interest in addressing the agency's estimated $40 billion-plus capital needs.

The MTA board convenes on Monday and Wednesday with the agency's walls closing in, financially and otherwise. Here's what you can expect:

The MTA is in fiscal trouble

After a long delay — which cost the agency $30 million each month — the board will finally vote on fare and toll increases on Wednesday.

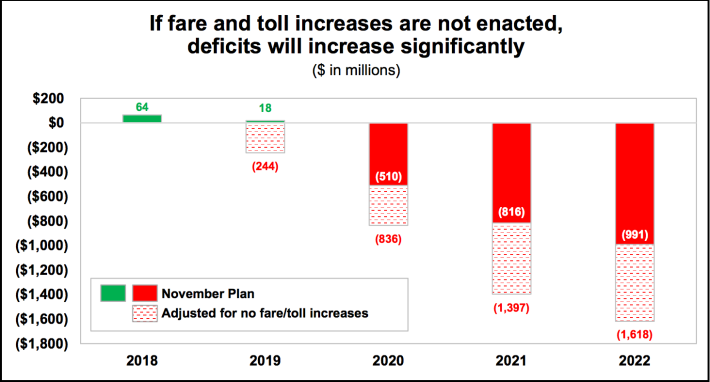

Even with the hikes, the MTA's projected budget shortfalls are big and getting bigger: $467 million in 2020 and nearly a billion by 2022.

MTA Chief Financial Officer Rob Foran has repeatedly warned that the MTA would have to enact dire service cuts without an infusion of cash. In such dire straits, the MTA has instituted a hiring freeze. On Friday, Politico reported that agency bigwigs are preparing for layoffs — ironic given the bump in personnel and labor costs since Governor Cuomo's 2017 "Subway Action Plan" emergency order.

Cuomo has argued that legislators have a choice between congestion pricing and 30-percent fare and toll increases, but the truth is that the MTA's financial needs far exceed the $15 billion congestion pricing would raise. Service and personnel cuts, therefore, are inevitable without more dedicated funding or, at minimum, the scheduled fare and toll hikes.

It's not clear what good simply gutting the place would do for riders.

"There’s clearly longer-term structural issues that we can address to make the MTA more efficient, but that’s just the point — they’re long-term," one MTA source familiar with the agency’s financial planning told Streetsblog in January. "We keep cutting in ways that are short-term. At this point, we’re going to start causing harm."

Cuomo moves for total control

Governor Cuomo has spent much of this year bemoaning his professed lack of authority over the MTA — even as he exercises control through the hiring of its top management and the appointment of the biggest bloc of board members.

The governor finally offered a vague plan in the 30-day budget amendments released on Feb. 15, proposing a six-person "expert panel" that would functionally supersede the MTA board by not only determining the congestion pricing fees, but also reviewing and approving the MTA's capital and operating budgets. The proposal does not say who would appoint the panel.

MTA watchdogs scratched their heads. "This is not the time to make major changes to redistribute power over the MTA’s governance structure, as there are too many stakeholders at risk," Reinvent Albany senior analyst Rachael Fauss said in testimony to senators on Tuesday.

Sadly, MTA board members, forced to oblige Cuomo's opposition to fare and toll increases at the expense of the agency's financial well-being, are powerless to fix things.

Board member Veronica Vanterpool, who is appointed by Mayor de Blasio, took to Twitter to question the logic of adding yet another layer of accountability to an agency overflowing with it:

The @MTA is overseen by #NYS Authorities Budget Office, @NYSA_Majority & @NYSenate Corps, Auth & Comm Cmtes, MTA Inspector General @NYGovCuomo @NYSComptroller @NYCComptroller. And ANOTHER MTA oversight body is proposed? That's dysfunction #30dayamendmentshttps://t.co/SBQkMXUUkW

— Veronica Vanterpool (@Veevanterpool) February 15, 2019

Local execs Missing-in-Action

Where are the mayor and county executives on this? By and large, they seem willing to hand over any leverage they have to the governor. Last week, Nassau County Executive Laura Curran conceded a months-long fight with the governor over her single vote on the board, nominating Cuomo's preferred candidate, a 77-year-old real estate executive, instead of the hero cop widow Patti Ann MacDonald.

That executive, David S. Mack, was vice chairman of the MTA from 1993 to 2009 — meaning he's one of the many people responsible for the current mess. In 2008, after then-Attorney General Cuomo made free EZ-Pass given to MTA board members illegal, Mack mocked transit as an "inconvenience," conceding to the New York Times that he only rode the train five to 10 times a year.

That's the type of MTA Cuomo is putting together, and de Blasio appears to be okay with it, tiptoeing around Cuomo's congestion pricing push while neglecting to leverage city residents' taxes, fares, and tolls — which already fund the vast majority of the MTA's budget, according to analysis by the Citizens Budget Commission.

You'd think the mayor would be more concerned about a congestion pricing plan that chips away at the city's already limited home rule powers by giving the state carte blanche to park its tolling infrastructure wherever it wants without any review or oversight by the city.

Enter Andrea Stewart-Cousins?

The prospects for congestion pricing are murky as ever and legislators aren't eager to come up with alternatives. Speaking to Streetsblog earlier this month, Senator Joe Addabbo (D-Queens) attempted to clear himself of responsibility.

"The Queens delegation met ... and as a delegation, we all agreed, we need more details," he said. Addabbo suggested that MTA officials lacked "initiative to think creatively" in addressing their funding troubles.

The governor's proposals do deserve scrutiny and the MTA should find ways to cut costs. Neither of those things excuse inaction.

Enter Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, newly unafraid to assert her power in the wake of the Amazon deal's collapse, which Cuomo blames on her caucus. That blame runs so deep, apparently, that Cuomo has already given up on defending the Democratic Party's clearest senator majority in nearly five decades.

"It doesn't spell trouble between me and them," Cuomo said of the Senate Democrats in a radio interview on Friday. "It spells trouble between them and the state of New York."

The governor may be overstating his own leverage. Stewart-Cousins holds the key to Cuomo's other priorities, including his nominee for MTA chief executive. It's not likely she give up her caucus's newfound political power. MTA observers hope her practically unprecedented move to hold an MTA oversight hearing in New York City early in the session bodes well for the future.

The growing distance with the governor offers legislators a chance to distinguish themselves. Last week, senators convened their first MTA oversight hearing in five years (the assembly has not be similarly eager).

“This is what democracy looks like," said Reinvent Albany Executive Director John Kaehny. "You build a culture of accountability by moving forward, not by having the revolution once every century."

Byford keeps chugging along

Cuomo's decision to take the L-train shutdown out of New York City Transit President Andy Byford's hands must have aggravated the 30-year transit professional, whom Cuomo hired a year ago with the broad mandate to fix the city's transit system. Byford set out to do just that, even daring to give it a pricetag: $39 to $60 billion.

That must have irked the governor, who wants the relatively paltry $15 billion congestion pricing will raise to avail him of further fiduciary responsibility. Speaking to business bigwigs earlier this month at a lunch hosted by A Better New York, Cuomo mocked Byford's budget estimates.

“That’s not a range. That’s a guess," the governor said with a smirk.

(Update: After initial publication of this article, Byford emailed us with a request to insert more context, which is below:

I have publicly stated that Fast Forward needs $40 billion over 10 years. This would be in addition to what we would normally expect for state of good repair (Fast Forward modernizes the infrastructure while state of good repair keeps what we currently have in good order). My pitch is we can totally modernize transit within just 10 years for a cost delta of $4 billion a year, a price that is very worth paying.

So I did not give out a $40-$60 range that was promptly mocked as a guess. The $60-billion figure relates to the whole MTA including the railroads. I am very confident of the Fast Forward costings.)

In the same speech, Cuomo mocked the MTA's unionized workforce and bemoaned the agency's dysfunction as an example of "nobody" being in charge — despite his effective control of the agency.

The governor's apparent frustration with Byford's funding requests is already impacting the outlook for his "Fast Forward" plans. In expectation of receiving just $30 billion, transit officials have cut back the number of stations they plan to make accessible from 50 to 36, the Daily News reported on Saturday.

And yet, Byford keeps chugging along. When transit journalist Aaron Gordon of Signal Problems questioned whether NYCT would provide adequate service during L-train single-tracking, Byford issued a statement assuring riders he's still in charge.

“As the person accountable to New Yorkers for the safe and reliable operation of this revised plan, I will insist on whatever measures and whatever operational flexibility I need to achieve that objective," he told Gordon.

And this weekend, Byford shared good news: on-time performance is the highest its been in four years — and delays the lowest.

Still, ridership continues to plummet — down 2.6-percent on the subways and 5.9-percent on the buses this year over last.

"While the MTA is making progress, the reality is it's still working with 50 year old trains and 100 year old signal technology," Riders Alliance spokesperson Danny Pearlstein said. "The only way to fix those problems is for the governor and legislature to fund Andy Byford's Fast Forward plan."

Improvements will never come fast enough, but they're coming. Whether Cuomo let's Byford continue that progress remains an open question.

Story was updated on Monday morning to include a new comment from Byford.