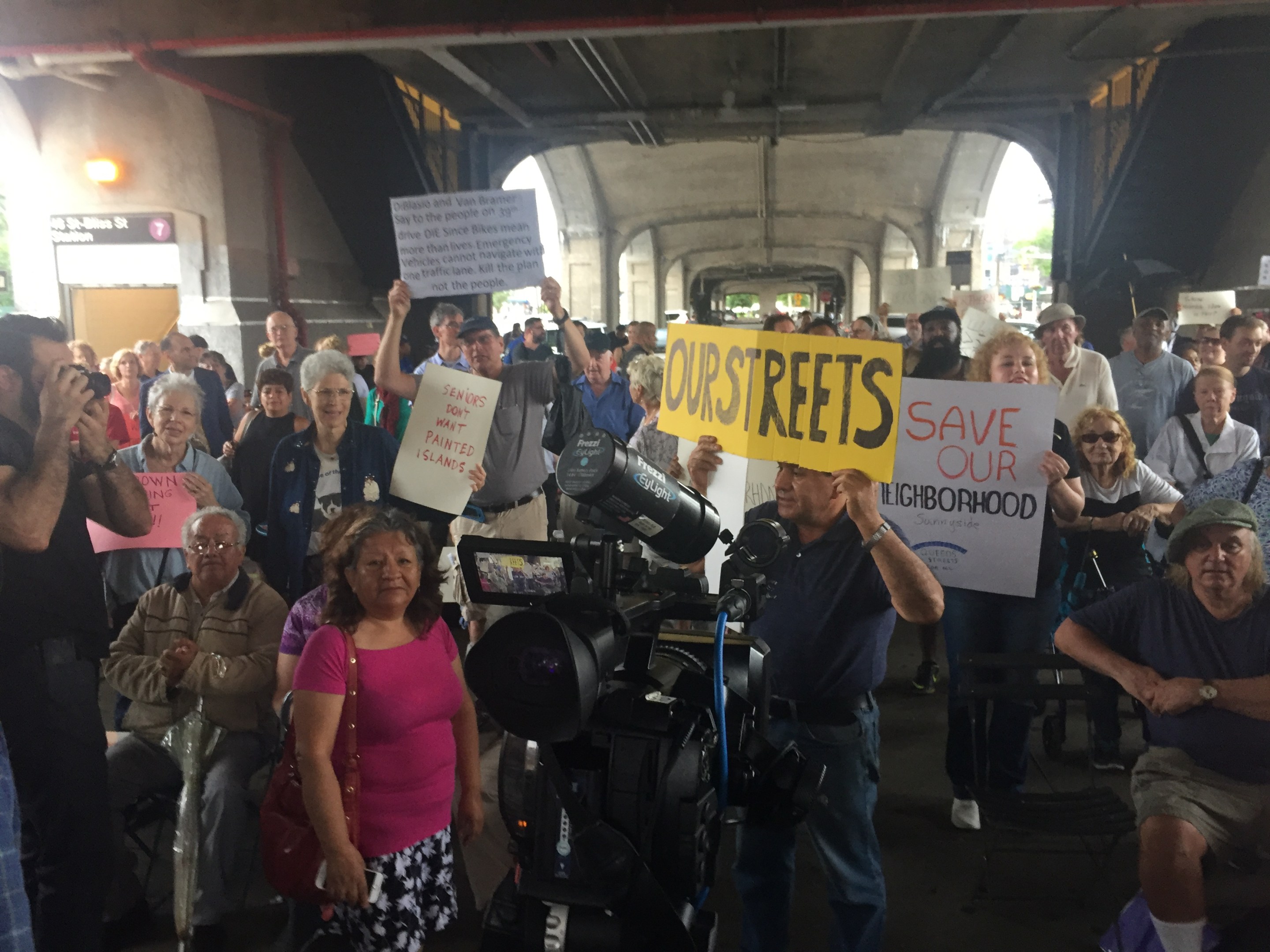

Last night's 50-minute pep rally for the already-lost battle to stop the upcoming implementation of protected bike lanes on Skillman and 43rd avenues was certainly not lacking for enthusiasm. Brandishing signs with messages like, "Save Our Neighborhood" and "OUR STREETS," the crowd of around 120 looked even larger as curious passersby paused to watch after exiting the 7 train into the "Sunnyside Arch."

What they had in enthusiasm, they lacked in facts.

"This is not about parking spots, this is about our neighborhood," Community Board 2 Chair Denise Keehan-Smith told the crowd, before listing off unsubstantiated, and in some cases, repudiated, allegations that the lanes will be unsafe for emergency vehicles and seniors and children. Keehan-Smith is a recent arrival to those talking points. Having joined the call for protected bike lanes after Gelacio Reyes' death last year, she balked when DOT presented its plan last November, calling the loss of 158 parking spots — since reduced to 116 — "highly unreasonable."

By and large, the event's speakers and attendees were concerned with one of two things: their own access to parking and the alleged, but unproven, impact on small businesses from the city reallocating about one to four parking spots per block for pedestrian and bike safety.

"Some of the stores have already said, at the end of August, they may not be able to last because the businesses have clients and cars," Master of Ceremonies Pat Dorfman told the crowd. "I have nothing against bike lanes, but we have to protect our businesses, churches, civic groups — parking here is already a nightmare."

Bike lanes have gone in across the city, and small businesses have done just fine. The man who's managed to convince Sunnyside residents otherwise is Aubergine Cafe owner Gary O'Neill.

Before DOT's plan came out, O'Neill actually signed onto Transportation Alternatives' petition for protected bike lanes on Skillman and 43rd avenues. He now claims that he was misled and that no one mentioned protected bike lanes, even though the letter he signed is explicit in that demand.

O'Neill's refusal to own his actions is just the tip of the iceberg of his and others' bogus and farcical arguments against the project, and a cautionary tale about fighting misinformation with facts in an age when objective truths are constantly under attack. Speaking to Streetsblog after the rally, O'Neill claimed that the bike lanes would impede the ability of fire trucks to make turns and that installing protected bike lanes requires at least three lanes of car traffic and hasn't been done anywhere else in the city. He argued that his customers who arrive by car aren't willing to opt for public transit instead and questioned the city's goal of reducing the number of people killed on city streets to zero.

"We can't legislate for every street in New York city," he said.

"I drove over to Long Island City, on a Sunday morning 11:30, some weeks ago. Just wanted to park the car, and have a late breakfast just sitting in the park. I couldn't get a parking spot, right? So I'm not going to go back and do that in Long Island City again," he said. "They're not going to take the train. They're drivers. They drive."

O'Neill's wrong on every one of his points. The local FDNY engine house did express concerns about the initial design, but those concerns have been addressed — and now the FDNY has approved the project, according to both DOT and the fire department. Meanwhile, plenty of protected bike lanes exist on NYC streets narrower than the typical Manhattan avenue.

O'Neill also said both Skillman and 43rd are not currently unsafe. He is wrong: The recent push for a redesign was sparked by a tragedy and near-tragedy last spring, but the fight for traffic-calming on Skillman is over a decade old, as TransAlt Queens chair Macartney Morris noted earlier this week on Twitter. Between 2010 and 2014, there were 15 severe injuries, nine of which were people biking or walking, on the roadways, according to city data. Since 2010, two people have been killed on the two streets.

With more and more people biking and walking in Queens' growing neighborhoods, ensuring safety to prevent the next fatal crash is imperative. Across the city, protected bike lanes have led to reductions in traffic injuries and fatalities for all users on streets where they've been implemented.

The bike lane opponents are right about one thing: the mayor has chosen to ignore the community board and build the protected lanes. Protesters called that a subversion of democracy, but it is not, by definition. The mayor is elected; the community board is not. And the neighborhood's elected council member, Jimmy Van Bramer, sailed to a third term last fall after demanding protected bike lanes on 43rd Avenue.

Spooked by the opposition, Van Bramer ended up not fighting for the project, something he now says he "regrets." Van Bramer says to expect a statement from his office today, which he told Streetsblog, bike lane opponents "will hate me for."

Judging from last night's crowd, which jeered and booed his name whenever it came up, they already do.

Asked for his take on how the council member played the months-long debate, O'Neill did not hold back.

"Played — that's exactly how we feel. We're upset," he said. "I think Jimmy listened to a few loud people on Twitter instead of his local community."

"Most of the people around here that voted for Jimmy, and they voted for him for many reasons, protected bike lanes was not on that list."