As closed-door budget negotiations in Albany shamble toward a conclusion, the emerging consensus is that Governor Cuomo and legislative leaders won't include a full congestion pricing plan in their deal. Instead, some sort of fee on taxi and ride-hail trips in the Manhattan core will be enacted this year, and Albany will punt on the cordon toll that would generate most of the benefits of a congestion pricing system.

The rosy scenario would then go like this: Cuomo and company include $200 million in the budget this year to implement E-ZPass gantries or other technology around the toll cordon proposed by the Fix NYC panel (Manhattan below 60th Street, roughly). Then after the November election, Albany takes up the question of toll reform in the next session, and passes a cordon fee structure at the high end of what Fix NYC recommended.

That's not an impossible timeline, but the risk of everything falling apart is high. If all that comes out of this session is a surcharge on for-hire trips, it will be another failure in a long line of Albany failures to deliver a robust traffic reduction policy.

Cuomo has shown little inclination to fight for a good congestion pricing plan, and barring a last-minute miracle, he should be held accountable for dangling the Fix NYC proposals without getting the full package through the legislature this session.

But the governor had plenty of accomplices too. Cuomo's lack of effort shouldn't overshadow the dismally passive performance of NYC's state representatives.

The Daily News surveyed all NYC representatives in the Assembly and found an interesting pattern. Outright opponents of congestion pricing are actually not that numerous, but there are a lot of fence-sitters. For every Robert Rodriguez, Joanne Simon, or Dan Quart who's on the record as a staunch congestion pricing supporter, there's a Deborah Glick or Danny O'Donnell who hems and haws.

The people who never took a strong position could have tipped the scales toward legislating the full congestion pricing package this year. Functionally, their indecision isn't any different than opposition. The result is the same -- no congestion pricing, same old gridlock choking the streets.

For most of these undecideds, the decision shouldn't be that hard. They represent districts where most people depend on transit, car traffic is a huge drag on neighborhood streets, and very few commuters would pay a congestion fee.

Representatives in the "inner ring" of Brooklyn and Queens stand out for doing a huge disservice to their constituents. Neighborhoods like Astoria, Greenpoint, and Williamsburg would see substantial knock-on effects from a cordon toll: Even though they're outside the congestion zone, the fee would reduce motor vehicle trips that pass through their districts on the way to Manhattan.

The Daily News outed many of these representatives as do-nothing legislators when it comes to the most important transportation initiative on the Albany agenda this session.

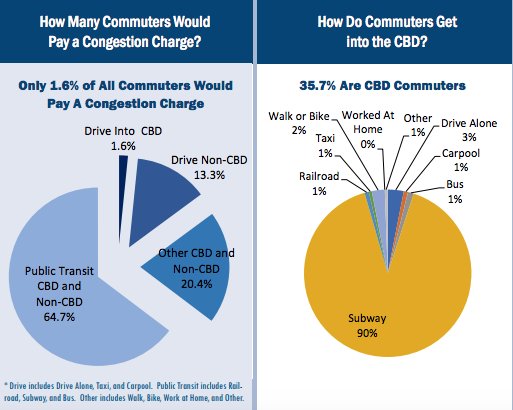

In all of the following districts, transit commuters to the Manhattan core outnumber car commuters by at least 15 to 1, according to the Tri-State Transportation Campaign's analysis of Census data. Yet none of the elected officials would go on the record supporting congestion pricing:

- Aravella Simotas, representing Astoria

- Joe Lentol, representing Greenpoint and Williamsburg

- Maritza Davila, representing Williamsburg and Bushwick

- Tremaine Wright, representing Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights

We contacted these four representatives today to get explanations of their positions. Davila and Simotas responded.

"The assembly member is for the fees being placed on for hire vehicles entering Manhattan as she sees it being equitable to what the taxi industries pays into the MTA," said Davila's chief of staff. "Her concerns are with the tolls for everyday drivers commuting to work and what impact that will have on working class families living in her district."

Simotas sent an even more anodyne statement. “New Yorkers deserve reliable and fast public transportation and a dedicated funding stream is essential to achieving that," she said. "That is why I support the Assembly’s Transit Sustainability Proposal and I’m also open to other ways of ensuring adequate funding for NYC Transit." In other words, she is willing to support the for-hire vehicle fee but not the congestion pricing package.

Who are these electeds looking out for? Most working class Manhattan-bound commuters in their districts, like the other districts we've highlighted here, rely on transit to get to their jobs. Very few workers -- less than 3 percent of all commuters in their districts -- are driving to Manhattan.

Among those who do car commute to the congestion zone, transit is probably a good option for the vast majority. Bruce Schaller's 2006 report, "Necessity or Choice" [PDF], revealed that 90 percent of car commuters to the Manhattan central business district could substitute transit for driving.

"Necessity or Choice" still has a great ring to it -- and it frames the situation in Albany well. Too many of New York City's state representatives would rather indulge the choice to drive, with all the traffic and pollution that imposes on other people, than set policy that will deliver the transportation system their constituents need.

David Meyer contributed reporting to this post.