German transit planners have a saying: organization before electronics before concrete. The idea is that to make the most efficient use of resources, decisions should flow from a particular logic.

Better coordination between different agencies enables transit system design that can serve the most people most efficiently, saving huge sums in the long run. Better signaling and trains get more value out of existing infrastructure, while coming at some cost. And tunnels can expand capacity and reach, but are the most expensive type of investment.

Unfortunately, New York has never mastered the most important part -- organization. The transit agencies that operate across state borders are notoriously poor at coordination. And even within the MTA, turf wars between different divisions are legendary.

So when the region does get around to building train tunnels, they are wildly expensive but still don't enable the service improvements we should expect from new transit infrastructure.

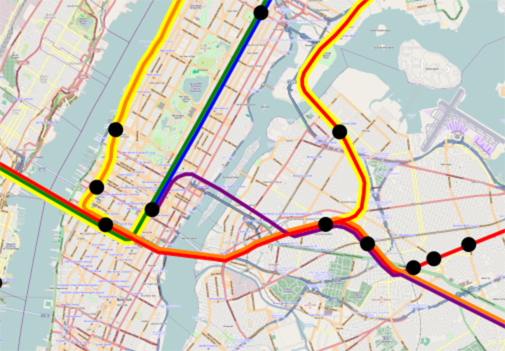

In its recently-released Fourth Regional Plan, the Regional Plan Association proposes a regional rail network that calls for integrated operations instead of the current silos between NJ Transit, Metro-North, and the Long Island Railroad.

Integration is very much worth pursuing. There are tell-tale signs, however, that RPA didn't put "organization" first. Namely, the plan calls for expensive tunnels that wouldn't be necessary if LIRR agreed to reasonable arrangements to share its tracks with other services.

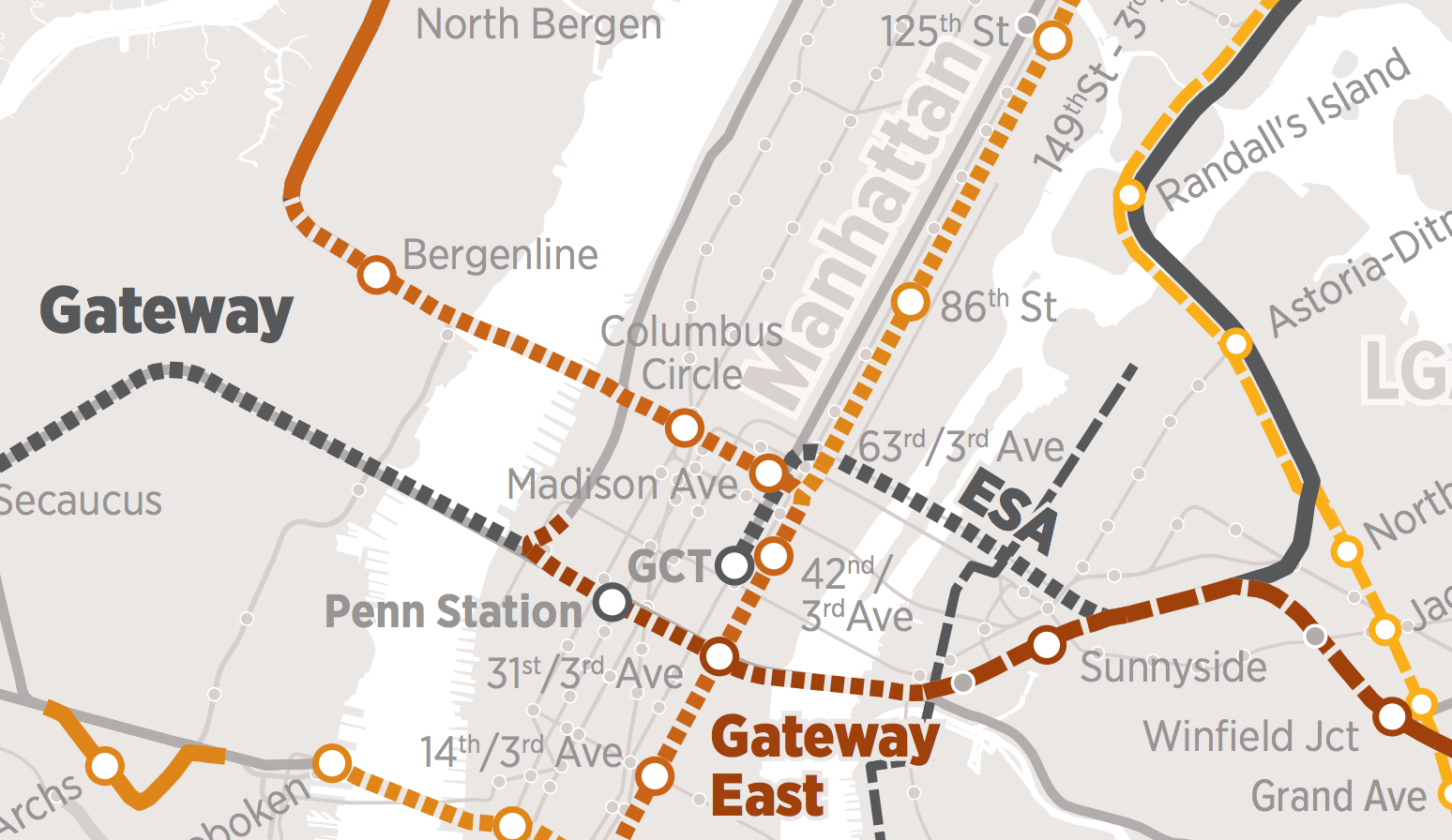

The RPA proposal begins with the Gateway tunnel, adding two rail tracks under the Hudson to double capacity between New York and New Jersey. That much is necessary, but it doesn't stop there.

RPA also calls for two new rail tracks under the East River, on top of the existing four, plus two tracks that will open up by the mid-2020s, when the East Side Access project adds a direct LIRR connection to Grand Central.

These seventh and eighth tracks, connecting Penn Station to Long Island, are estimated to cost $7 billion. But there is no capacity crunch between Manhattan and Long Island that justifies more tracks, especially after East Side Access opens.

Even today, total inbound traffic at the peak is 36-37 trains per hour on the LIRR and another four on Amtrak, against a rated capacity of 48 for a four-track tunnel.

A major hurdle is LIRR's unreasonable demand to keep all of its 37 rush hour slots into Penn Station even after East Side Access opens. The LIRR projects to send 24 trains per hour into Grand Central. The LIRR and Long Island politicians insist that future growth in demand induced by the opening of East Side Access will likely fill those 24 hourly trains to Grand Central plus 37 to Penn Station.

This is why both the railroad and Long Island politicians oppose Metro-North's Penn Station Access project: They worry it could take Penn Station slots they think belong to the LIRR by right.

However, significant ridership growth on the LIRR is unlikely, because Long Island is not adding any housing. Nassau and Suffolk Counties both permit much less than one housing unit per 1,000 residents per year, according to HUD. Without massive transit-oriented development on Long Island, to the tune of tens of thousands of annual housing units every year, the future growth argument holds no water.

Meanwhile, a more useful piece of tunnel is absent from the plan: a connection between Penn Station and Grand Central. This connection was proposed in one of the variations for the predecessor to the Gateway project, known as ARC Alt G, and it remains feasible today. Building it would enable through-running between the New Jersey Transit and Metro-North networks.

Earlier this year, I spoke to RPA President Tom Wright about a preliminary version of the regional rail proposal. At the time, he said RPA was still considering the Penn-Grand Central tunnel for inclusion in the Fourth Regional Plan, but that the preliminary report only focused on infrastructure required for the Gateway project.

But the Penn-Grand Central link is not in the final plan, and Wright's explanation also raises the question of why RPA included the seventh and eighth East River tracks in its earlier plan. The answer must involve the toxic relationships between the different railroad bureaucracies, and the difficult politics of getting the LIRR to share track.

If the LIRR assesses its future service plan realistically, New York can have an integrated regional rail network at far lower cost, forgoing a $7 billion tunnel under the East River. (The connection between Penn Station and Grand Central would not be free, but it's entirely underground rather than underwater, which should make it much cheaper than tunneling under the East River.)

The politics of compelling the LIRR to share track may be challenging, but the same could be said for many components of RPA's plan.

At the very least, someone needs to impress on Governor Cuomo the importance of integrating transit service and infrastructure. If New York is going to build a good regional rail network in our lifetimes, political heavyweights will need to insist on organization before concrete.