Monday’s City Council transportation committee hearing was notable not just for City Hall’s dismissal of Move NY’s new home-rule congestion-pricing plan but also for the weak tea served up by city transportation officials.

Their testimony was long on slippery promises like creating "a culture of compliance on placards" and "a comprehensive plan to better manage curb space," and woefully short on action. “Tinkering around the edges” is how Council Member Corey Johnson characterized the administration's plans.

What stood out for me, though, beyond DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg’s rote rejection of the Move NY initiative, was her assertion that “economic theory tells us that congestion is self-correcting.”

Here’s the context:

Council Member Steve Levin: Is congestion getting worse? Does it ever get better?

Commissioner Trottenberg: Taxi data shows CBD travel speeds worsening from 2010 to 2016, from 9.5 mph to 8.0. Congestion is tied to the economy. When I lived in Park Slope in the early eighties, congestion wasn’t as bad, I could find a parking space. [But] economic theory tells us that congestion is self-correcting. People will use other means if it gets bad enough. But we have to provide the other means.

Calling congestion "self-correcting" is a convenient way to steer the subject away from congestion pricing. The argument is that drivers can bail when congestion "gets bad enough." Problem solved -- without collective (governmental) action requiring political leadership.

Let’s unpack that. It’s true that drivers going into congested areas have learned to anticipate that other cars on the road -- i.e. "traffic" -- will slow them down. Yet drivers are largely unaware how much their trips will slow down traffic at large. Indeed, we don’t find drivers pondering the time their trips take away from others on the road, since they aren’t charged for taking it.

To be sure, when traffic is light, those "time costs" tend to be trivial. My trip hardly slows down traffic, and there are so few other vehicles that any delays due to my driving won’t amount to much. But in the heavy traffic conditions that typify NYC streets -- especially in and around the Manhattan Central Business District -- those delay costs can be substantial.

What economic theory actually says about traffic congestion, then, is that without a congestion charge, the delays my trip causes others are externalized. I impose them but I don’t pay for them. And since I don’t pay for them, I’m more likely to drive in crowded traffic and thus contribute to congestion. The same goes for everyone else using (or considering use of) the roads. Together, we’re incentivized to drive more and, thus, take more time from each other collectively than we stand to gain individually by taking the car.

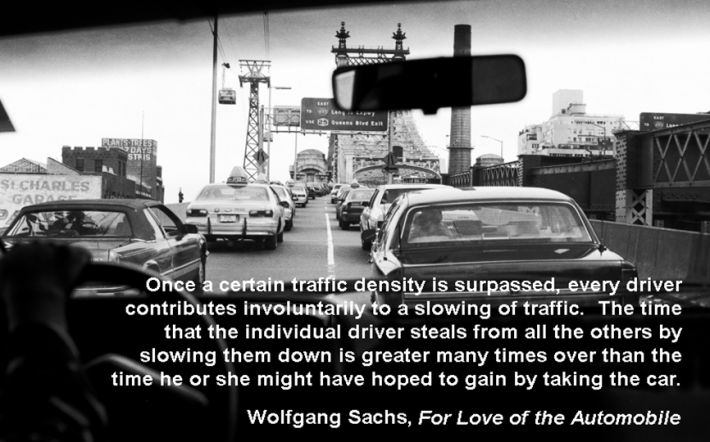

This simple yet profound insight distills the “problem” of traffic congestion to its essence. I came across it in clarion-clear language 25 years ago in a book chronicling German resistance to motorized transport in the early 1900s, For Love of the Automobile, by the cultural historian Wolfgang Sachs. Fellow activist Steve O’Neill turned it into the above graphic, which I’ve used in my traffic-pricing talks ever since.

Why dwell on this? After all, Trottenberg was probably just toeing City Hall’s line at the council hearing: Congestion pricing is nice in London and Stockholm but we’ll get by without it here in New York.

Here’s why: The congestion antidotes the administration presented to the council are fated to fail, for the most part. Not only are they small bore (ferries) or costly (subsidizing night-time freight delivery; ferries). More fundamentally, unless they’re back-stopped by a congestion price, any space on the road they free up will soon be filled by new trips made by opportunistic drivers.

Traffic does seek its own level, but that level is determined by whether and what we charge to use the roads. No matter what we do with signals and enforcement, and even with transit, we won’t keep the street space we think we’ll gain unless we charge vehicles for occupying it.