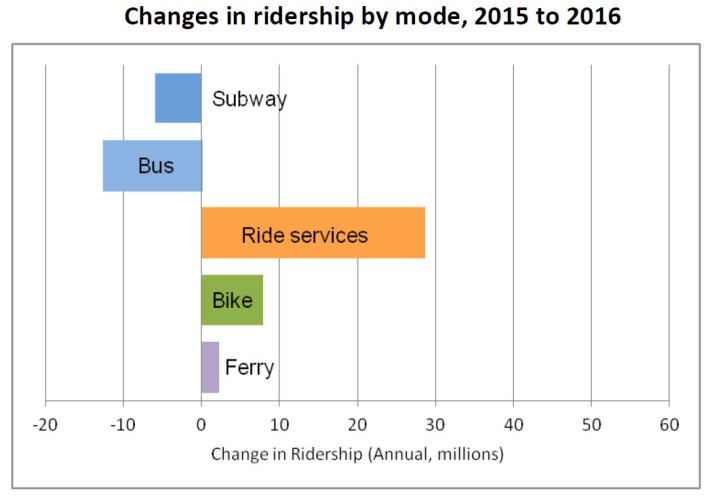

For the first time in a generation, cars account for most growth in travel in New York City instead of transit, as Uber and Lyft crowd the streets, according to a new report from Bruce Schaller.

Growing congestion and declining transit ridership are symptoms of a transportation system in distress. But at a moment when transit in NYC desperately needs smart stewardship to meet rising travel demand, the city's political leaders, especially Governor Andrew Cuomo, are nowhere to be found.

Last night at a panel hosted by TransitCenter, 1199 SEIU Political Director Lillie Cariño-Higgins and former Port Authority chair Chris Ward, currently an executive at engineering giant AECOM, laid out why working-class New Yorkers and the city's business elite are both affected by the faltering transit system. (Watch it here.)

Many of the 200,000 healthcare workers 1199 represents take transit to work because it's the only affordable option. But unreliable service costs them time, said Cariño-Higgins, with trips that should take 15 or 20 minutes according to the schedule often dragging out to 50 minutes or an hour.

"The MTA really has to do a better job of meeting [our members'] needs to get to and from work," she said. "And it’s not just about work. It's about shopping. It’s about everything -- visiting families, getting to church on Sunday. This is how our members get around."

New York is also a city where employers draw enormous benefits from the massive pool of people who can reach central locations thanks to the efficiency of the transit system. If that system can't keep up with rising travel demand, said Ward, the city's economic engine will start to sputter.

"What makes New York City grow economically is driven by how well people can get to work within the wealth centers," he said, "and I think we’re reaching a point where the real estate industry itself is going to see move-outs from the Central Business District into other parts of the region."

Subway crowding and delays are surging, while bus speeds continue to deteriorate. Unless the city and especially the MTA take steps to increase the core capacity of transit, said Schaller, more people will continue to choose Uber or Lyft, and the city will get squeezed by gridlock. "People are opting out [of the subway] because of the conditions," he said, "and that's what we need to be tackling."

The improvements Schaller has in mind are systemwide: modern subway signals that let trains run closer together, faster bus boarding and fare payment, and more bus-priority treatments on city streets.

Meanwhile, Cuomo has spent much of his tenure pushing highway and bridge projects, transit boondoggles, and tech gimmicks.

When the governor wants to expedite an important project, he can -- witness the race to get the Second Avenue Subway into service by Cuomo's deadline. But the governor has shown none of the same urgency for systemwide improvements that would speed trips for all riders and increase capacity across the board.

The MTA started testing a modern, high-capacity signal system in the 1990s, for instance, and awarded a contract to Siemens to start implementation in 1999. Nearly two decades later, modern signals are fully operational on just one subway line.

“We have been talking about the signal system for 20 years," said Ward. "We need to figure out a way for the MTA and large public agencies to be far more nimble in delivering transit improvements than they have been capable of doing."

And when advocates raised alarms about declining bus speeds and called on the MTA to commit to faster fare collection technology across the system, Cuomo did nothing, and the agency dragged its heels.

Without a governor focused on improving the daily experience of riding the trains and buses, for-hire vehicles will continue to fill the vacuum and gridlock will get worse.

“If we can build the Tappan Zee Bridge in record time," Schaller said last night, "maybe we can get these things installed in record time."