This is part three of a five-part series by former NYC DOT policy director Jon Orcutt about the de Blasio administration’s opportunities to expand and improve cycling in New York. Read part one and part two.

Applied to cycling, Mayor de Blasio's "two cities" campaign theme would argue that the safety and accessibility benefits conveyed by bike lanes in New York should be enjoyed by people all across the city.

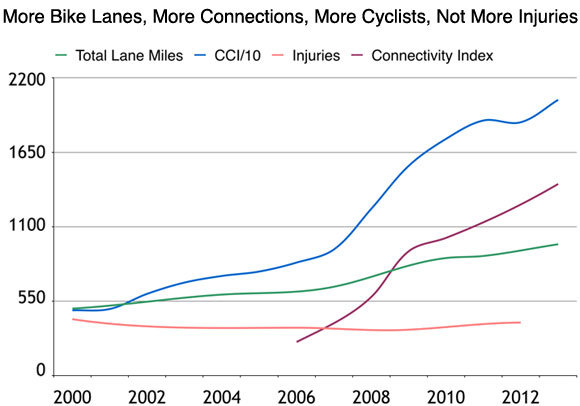

The high degree of bike lane density implemented in the Manhattan CBD and Brooklyn north of Prospect Park during the second half of the Bloomberg years allowed for huge cycling increases in that area, and laid the groundwork for Citi Bike and future bike lane development across the city. More than any other factor, the increasingly dense interconnection of bike lanes in a relatively small area led more and more people to carry out daily trips by bicycle.

In the recent history of NYC cycling, the years with the greatest percentage growth in the city’s official bike counts dovetailed with the strongest percentage gains in a metric devised by NYC DOT planners to assess the connectivity of the bike network. The city’s bike counts, which track cyclists crossing the boundaries of the central business district, more than doubled from 2006 to 2010. This period was years before the advent of Citi Bike, and even by the end of 2010, only a few miles of on-street protected bike lanes had been implemented. But in each of the years 2007, 2008, and 2009, the bicycle network connectivity index registered increases greater than 50 percent.

The rest of the city should benefit from the ongoing deployment of a finely grained bike network. The areas perhaps ripest for development are the types of districts that Mayor de Blasio has pledged to bring more attention to.

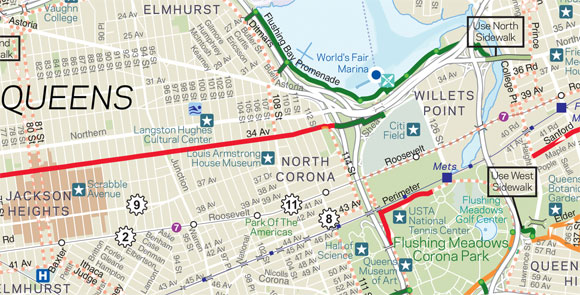

Consider examples in central Queens and the southern Bronx. The neighborhoods of Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Corona, and Lefrak City are largely bike lane deserts today, but a few additional east-west and north-south bike lanes there could capitalize on the existing network spine along 34th Avenue to begin to forge grids of bike-friendly streets. At the edge of Corona is the Flushing Bay Promenade, currently disconnected from any other element of the bike network. North/south lanes or marked routes connecting to the Promenade's access points would begin to form a network with the 34th Avenue bike lane.

The Corona street grid's connection to Flushing Meadows Park is another nearby opportunity. Ironically, the park today presents a barrier rather than a connection for bike trips across Queens, because of the highways flanking it and the confusing and awkward layout of paths and roads within the park. A joint Parks Department/DOT effort to better identify and solidify bike routes across the park could be linked to development of east/west bike routes in North and South Corona.

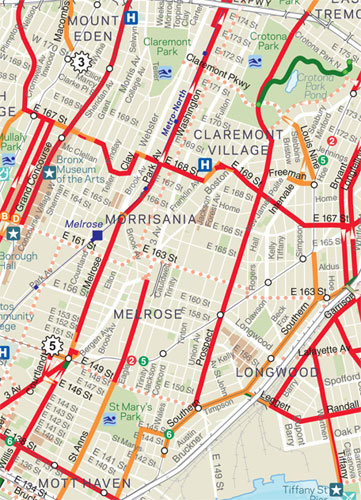

In the Bronx, the city has laid a stronger bike network foundation. Long north/south bike lanes are already in place. There are opportunities to upgrade some of this infrastructure -- converting the lanes on the Grand Concourse service roads into parking-protected lanes, for example, would be a huge boon to bike transportation in the Bronx. Meanwhile, some north-south trips remain difficult, including getting between Hunts Point and Mott Haven. There is room along Bruckner Boulevard, which has few intersections along its eastern side, for a barrier-protected bikeway from the 130s to Hunts Point. It wouldn't be the most pleasant place to ride, but it would be direct and safe, which is what people going somewhere by bike want the most.

In any scenario, north-south bike axes in the Bronx need to be complemented with more east-west lanes and routes. Similar to Flushing Meadows, Bronx Park is more a barrier to cycling than a connector -- DOT and the Parks Department should jointly develop a way to link the streets in Belmont with the pathways along Pelham and Bronx River Parkways. The pending opening of the High Bridge adds another impetus for better east-west Bronx cycling routes.

These gaps in the bike network and potential solutions are only examples -- more opportunities abound in other parts of the city. Pent-up demand should also lead to substantial bike network expansion in Brooklyn south of Prospect Park and in Upper Manhattan, for example, and to the beginnings of a Staten Island network in St. George.

Tomorrow: A proposal to use the Harlem River bridges as the backbone of a great bike network for Upper Manhattan and the Bronx.