A report from the Department of City Planning issued during the final days of the Bloomberg administration is a trove of data about parking, but a look behind the pretty maps reveals a department that remains focused on dictating the supply of parking spaces and reluctant to use its power to reduce traffic and improve housing affordability. Mayor de Blasio and his to-be-announced city planning commissioner will have to fix this backwards approach to turn parking reform into an effective tool for the administration's affordability agenda.

Under Amanda Burden, the Department of City Planning acknowledged the negative impact of parking mandates on environmental and affordability goals, then ignored many of those concerns when it came time to setting actual parking policy. Instead, the Bloomberg administration preferred to tinker with decades-old parking mandates in a few locations while preserving them across most of the five boroughs, using the promise of off-street parking as a bargaining chip to quell residents skittish about new development.

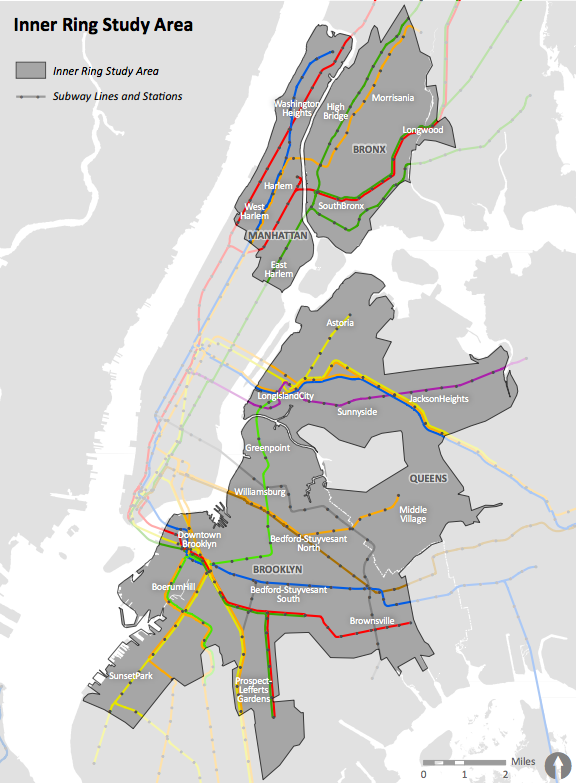

Absent a course correction from the de Blasio administration, this broken approach to parking could continue on auto-pilot. Timid half-measures that DCP made in the Manhattan core and Downtown Brooklyn appear set to spread to adjacent neighborhoods in the "inner ring" covering much of the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn and upper Manhattan.

In a report released last month examining parking in those neighborhoods, DCP set the stage for future policy changes by casting itself as the arbiter of parking demand. The report discusses how to adjust parking requirements to match that demand, rather than using policy as a tool to reduce traffic and drive down the cost of housing for all New Yorkers.

There is one bright spot in the report: the recommendations for income-restricted affordable housing. "Parking facilities are often expensive to construct and affect the cost of constructing residential buildings," says the report, noting that the median cost of structured parking in New York City is the highest in the country at $21,000 per space -- sometimes spiking as high as $50,000 per space. "Excessive parking requirements could hinder housing production, making housing less affordable," it says. But instead of applying this logic to all new housing, the report focuses narrowly on subsidized units.

"Affordable housing is more susceptible than market-rate housing to the cost implications of requiring accessory parking," the report says, noting that low-income residents are less likely to own cars and less able to pay for parking. "Updating requirements for affordable housing to better match the needs of its residents can reduce construction costs and enable more affordable units to be built."

This issue plays out constantly in the city. In Harlem right now, a developer is looking to reduce costs by building fewer parking spaces than required, and some community board members want the savings to go toward providing more affordable housing units, according to DNAinfo. But the implications for affordable housing aren't limited to subsidized units. If the city eliminated all parking requirements, more resources could be devoted to building homes and apartments, not car storage, and housing overall would become more affordable.

This policy of focusing parking reforms on affordable units is in line with changes DCP has already made in the Manhattan Core and Downtown Brooklyn, where parking requirements for affordable units have been eliminated entirely. It's also an avenue for parking reform that might be appealing to the de Blasio administration. But it does nothing to reduce the cost of new housing for New Yorkers who don't live in a subsidized unit.

Today, even transit-oriented areas in the outer boroughs with already-low rates of car ownership have parking requirements for new development, driving up the cost of housing. But DCP's latest report only contemplates reducing, not eliminating requirements in these areas. "It makes sense to have lower parking requirements in these neighborhoods," it says, without acknowledging that cities have ditched parking mandates in areas that have much less transit access than New York's "inner ring" neighborhoods.

DCP's report is focused on determining the number of parking spaces that should be provided and crafting a zoning code that will require new development to provide those spaces. "Modifications can be considered to better match parking regulations to neighborhood characteristics," it says. "In areas where parking requirements are higher than necessary, requirements can be reduced."

Sandy Hornick, a long-time DCP deputy director who oversaw much of the department's parking policy, retired at the end of last year. "We're trying to better understand the role that parking plays," he told the Wall Street Journal in 2010, "and adjust our policies accordingly."

But it's not the role of city government to forecast demand for parking and then adjust policy to compel developers to provide that parking. DCP acknowledges that parking mandates have a host of negative impacts, but still insists on requiring parking in new development. With the share of car-free households on the rise in New York, it's long past time for the city to get out of the parking demand projection business, and get serious about achieving its environmental and affordability objectives.

Parking reform is an issue Bloomberg barely touched. By taking it on, the de Blasio administration can make serious headway on its affordability goals.