In 2008, a coalition led by the Pratt Center for Community Development laid out a vision for 12 Bus Rapid Transit lines across the city. Nearly six years later, NYC DOT and the MTA have installed six Select Bus Service routes in four boroughs, with plans for more. At a panel discussion this morning, the Pratt Center unveiled a new report [PDF] showing eight routes that are ripe for Bus Rapid Transit, featuring upgrades like separated busways and stations with fare gates and platform-level boarding.

During the mayoral campaign, Bill de Blasio promised to build a BRT network of more than 20 lines citywide. The big question is whether he'll follow through after January and turn recommendations like the Pratt report into real policy.

"Select Bus Service is a breakthrough for our city," said Joan Byron of the Pratt Center. But SBS routes, criticized as "BRT-lite" for relying on striped bus lanes instead of dedicated busways, can only do so much for riders making longer trips in the outer boroughs, she added. "What the neighborhoods that are outside of the reach of the subway need is to put the 'rapid' into Bus Rapid Transit."

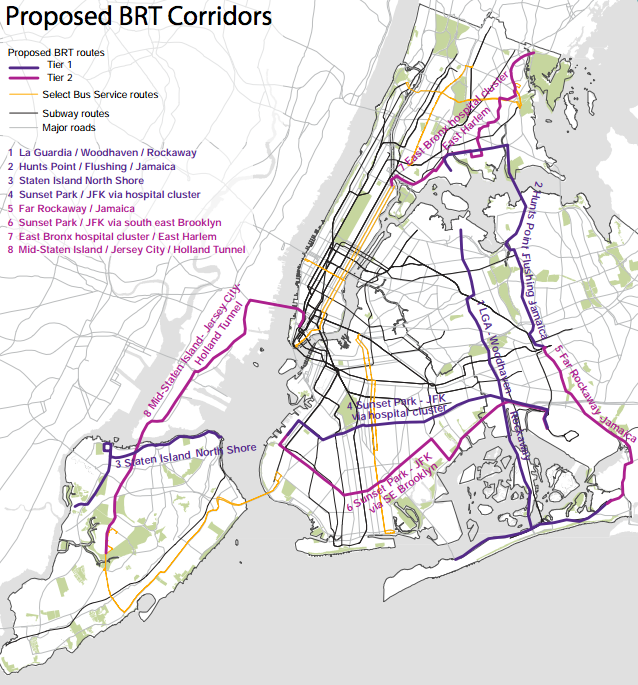

The report, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, identifies eight routes along corridors where 2.3 million people currently live within a half-mile. The routes are split into two phases: The first four are along wide rights-of-way with the capacity to host dedicated busways and stations, Byron said, while the final four are along trickier routes that could be easier to implement after the public judges the success of the first four.

The eight routes in the Pratt Center report are:

- LaGuardia Airport to the Rockaways via Woodhaven Boulevard and Cross Bay Boulevard

- Jamaica to Flushing via Main Street, continuing to Hunts Point in the Bronx via the Whitestone Bridge and Bruckner Boulevard

- Conversion of a rail corridor on Staten Island's North Shore to a multi-leg BRT route, currently in planning at the MTA

- Sunset Park to JFK Airport via Linden Boulevard, connecting with a cluster of medical centers in central Brooklyn

- Far Rockaway to Jamaica via Nassau Expressway and Rockaway Boulevard

- Sunset Park to JFK Airport via Kings Highway and Flatlands Avenue

- East Harlem to Co-Op City via a cluster of medical centers along Eastchester Road in East Bronx

- Richmond Avenue in Staten Island to Manhattan via Jersey City and the Holland Tunnel

Byron said the Pratt Center focused on these routes because many outer borough neighborhoods are seeing population changes as low-income households are priced out of areas closer to Manhattan with better transit access. "We've had population shifts that we're just beginning to understand," she said. "When I was growing up, this was the land of Archie Bunker."

Residents of these neighborhoods are stuck with unreliable buses that are too slow for the increasingly long-distance trips commuters must make. Growing job centers at airports, hospitals, industrial zones and retail hubs are often beyond the reach of a convenient subway trip. "We're talking about a potentially two-hour commute for some folks," said Austin Shafran, the recently-named legislative director of the Working Families Party. "BRT can be the great equalizer."

So far, implementing SBS routes has often involved years of planning. Delays have followed when a single community group or elected official (a state senator, perhaps) stood in the way of bus upgrades that could benefit thousands of riders each day. Mitchell Moss, director of NYU's Rudin Center for Transportation, singled out the city's Albany delegation for its inattention to the MTA, a state authority under its watch. "We have an undistinguished State Senate representation when it comes to transportation," he said. "We have to have people in Albany who care. It is not a priority for our state senators today to understand how important the MTA is. That's the failing."

Given the political and planning hurdles in the way, is it possible for the city to fast-track aggressive BRT plans, beyond the current one-a-year pace of more modest SBS improvements?

Byron thinks so. She said the SBS planning process has improved greatly in the past few years, with DOT staff working with local merchants on issues as fine-grained as block-by-block needs for loading space along a route. "They know how to do it," she said. "You've got to put more teams in the field so they can work on more than one route at a time."

The BRT routes proposed by the Pratt Center would redesign some of the city's most dangerous multi-lane roads, creating an opportunity for significant safety improvements for pedestrians and cyclists."If you can score a win-win by not only having a vastly stepped-up transit service, but use those same design interventions to create safe, complete streets," Byron said, "why wouldn't you do that?"

Public Advocate-elect Letitia James, who would like to see de Blasio appoint a deputy mayor tasked with prioritizing BRT and street safety issues, said she supports using tax-increment financing from new development along BRT routes to finance their construction. James noted that residents are often uneasy about infrastructure upgrades that could lead to further gentrification and displacement. She stressed that guaranteed benefits, such as upgrades to community facilities, signal that existing residents stand to benefit from new development. "When there are additional public benefits," she said, "then the community can support greater density."

"People think they're against density," Byron said. "What they're against mostly is displacement." Byron suggested that the city bring in other agencies, such as City Planning or Housing, Preservation and Development, to address a wide range of neighborhood concerns during planning for a BRT route.

Another key to speeding up the process is organizing bus riders themselves. "Bus Rapid Tranist becomes politically feasible when there's a strong constituency demanding it, and so it can surmount the challenge of one suspicious elected official or one community that's not convinced, if you're able to organize," said John Raskin of the Riders Alliance. "It's really valuable that Pratt and Rockefeller have put together specific proposals... It's a great opportunity to go out and organize riders."

Byron, who suggested organizing bus riders at large employment centers that stand to benefit from improved buses, said successful BRT could set the stage for even more ambitious transportation projects and reforms. "One of the reasons that congestion pricing in London was politically possible is that people saw the transit benefits right away, and those benefits were delivered primarily through improved bus service," she said. (New York's unsuccessful 2008 congestion pricing proposal was also tied to significant new bus service paid for with a federal grant.) Byron then mentioned the Move NY plan to raise funds for transportation by adjusting the toll structure on bridges across the city. "To set the stage for that to be possible, we've got to score some wins," she said, "and BRT is one of those wins."

While a healthy crowd turned out for today's event, the importance of the Pratt Center's report ultimately hinges on one reader: Mayor-elect Bill de Blasio. "If Mayor de Blasio wants to roll out 20 BRT routes in four years, that leadership has to be there," Byron said. "And what that leadership has to say to the community is: We will listen to you. We will take you seriously when you describe a problem. But that will not stop the process, because the benefit is to a much larger number of people. That's got to be the tone from the leadership."