East River Plaza, the big box mall designed for Massapequa and placed in East Harlem, still has a thousand-space parking garage. And given its location in one of the lowest car-ownership neighborhoods in the country, the garage is still as empty as when it opened, despite big subsidies for parkers.

Thanks to new research from Rutgers urban planning student Kyle Gebhart, whose paper on East River Plaza [PDF] won first prize from the American Planning Association's Transportation Planning Division, we now know just how badly the project's developers whiffed when building that massive garage.

To find out how the garage was being used, Gebhart went down to East River Plaza at two peak shopping times, the early evening of the Tuesday before Thanksgiving and the afternoon of the first Saturday in December. On the Tuesday, only 33.6 percent of the 1,103 spaces in the garage were occupied. On Saturday that figure had only crept up lightly, to 38.6 percent.

The top floors of the garage were essentially empty. Between 0.6 and 5.8 percent of the spaces on the upper levels were filled, according to Gebhart's survey. One section of the third floor of the garage had been fenced off and converted into storage space rather than parking.

In contrast, the developers predicted that the garage would hold a whopping 1,190 cars on an average Saturday afternoon in the environmental impact statement for the project.

How did they get it so wrong? As East River Plaza developer David Blumenfeld explained to Streetsblog after the mall's opening, he built his calculations around data from suburban big box stores. In the early 1990s, when the project was first conceived, there weren't any big box stores in more urban settings. "There was no model to go off of," said Blumenfeld. "There was only the suburban model."

Gebhart's research reveals just how braindead those planning documents were. The environmental impact statement drew its numbers from Home Depots in places like Pelham Bay Park, Glendale, Staten Island, and even Port Chester, where the store is off a highway interchange on the Connecticut border. Rather than assume a Manhattan location would have fewer drivers than those sites, they simply averaged the numbers from those suburban locations together.

"It is odd to somehow presume that a Manhattan Home Depot would generate an average number of trips from these locations," wrote Gebhart, with a fair bit of understatement.

To estimate the parking needs of the East River Plaza Costco, the EIS looked at a single site in Staten Island, again without any sort of adjustment. "This is therefore measuring the amount of parking in the most car-dependent borough and applying it to the most car-free borough," Gebhart wrote.

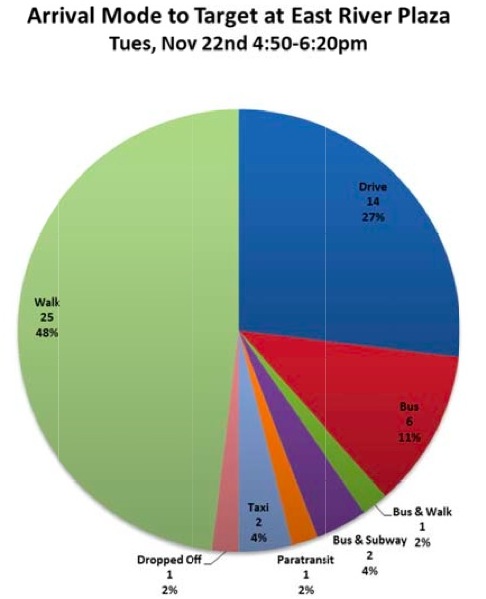

The results, needless to say, weren't a good fit for Manhattan shoppers. Over half of East River Plaza's customers live in the three closest ZIP codes, and by and large, they get to the mall on foot. Just under half of all shoppers Gebhart surveyed as they entered the Target on the Tuesday afternoon had walked there. Only 27 percent had driven.

Because the designers of East River Plaza had assumed most shoppers would be entering from the garage, not the street, the pedestrian environment is terrible for those entering on foot. Gebhart found that sidewalks on E. 117th Street had been narrowed near the entrance to the mall to make room for a wider street.

The moral, seemingly intuitive but not grasped at East River Plaza, is that you can't treat Manhattan like it's the suburbs. "If big box stores would like to locate in urban environments, it is important that they do not bring all of the elements of suburban sprawl with them," concluded Gebhart. "Otherwise, by continually increasing the supply of parking and creating dead spaces, the city will only become more auto-dependent and sprawled as well."