Yesterday, Chicago's Board of Aldermen passed an ordinance that would allow speeding enforcement cameras to blanket up to half the city. Here in New York, Deborah Glick's bill to allow up to a mere 40 speed cameras remains stuck in Albany limbo, with 24 co-sponsors in the Assembly but none in the State Senate. Can Chicago show New York City what it takes to prevent injuries and deaths by hold speeding motorists accountable?

Speed cameras produce enormous public safety benefits. One study by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety found that cameras reduced the number of drivers speeding by more than ten miles per hour by up to 88 percent. Lower speeds give motorists more reaction time to avoid collisions and drastically reduce the severity of injuries in the event a crash does occur. Struck by a vehicle moving at 20 mph, a person has a 98 percent chance of survival, according to the UK Department of Transportation. At 30 mph the survival rate drops to 80 percent, and at 40 mph only 30 percent of pedestrians survive.

While lower speeds make roads safer for all, automated enforcement usually encounters resistance from some motorists, and at first glance, it would seem the obstacles to rolling out speed cameras in Chicago are if anything greater than they are in New York. Like New York, Chicago needed to receive permission from the state legislature to install cameras. The constituencies for automated enforcement in Chicago look less favorable than in New York: At both the city and state levels, there are more motorists and fewer transit riders and pedestrians. And Chicago's 200 red light cameras have been depicted as revenue generators, not safety measures, increasing skepticism of automated traffic enforcement among legislators and leading to some close votes for the speed camera bill.

Still, Chicago's about to get speed cameras -- a lot of them. Why? Looking back at the history of Chicago's successful push for speed cameras, three potential lessons for New York City jump out.

Make It a Mayoral Priority

Speed camera legislation has the official support of New York City, with specific endorsements from the city Department of Transportation, the Department of Health, and the NYPD. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel's backing for speed cameras, however, was in a whole other league.

The Chicago Tribune called winning authorization for speeding cameras "one of the mayor's highest priorities" in Springfield, especially relevant since Emanuel is still in a bit of a honeymoon phase as a new mayor. To push the bill to passage, Emanuel was on the phone with legislators personally, according to the Chicago News Cooperative, making individualized cases to each.

The issue became impossible ignore. New York's speed camera bills have died in committee every year since 2001, without much fanfare. Chicago's bills garnered intense media scrutiny, with the press covering every step in the legislative process, scrutinizing the city's sometimes-faulty data, and muckraking about the lobbying for the bill.

New York City's last expansion of automated traffic enforcement, which permitted camera enforcement of bus lane violations, was quietly snuck into a bigger negotiation about student MetroCards. Chicago confronted the issue head on. Governor Pat Quinn signed the speed camera bill at a public event held at a Chicago school. "I think that you've got to understand that if you save even one life, you are saving the whole world," said Quinn at the time (echoing the Talmud).

If Mayor Michael Bloomberg started loudly advocating for Albany to allow speeding cameras, it would hardly guarantee passage. Without a doubt, though, it would force the issue into public view.

Emphasize Safety for the Most Vulnerable

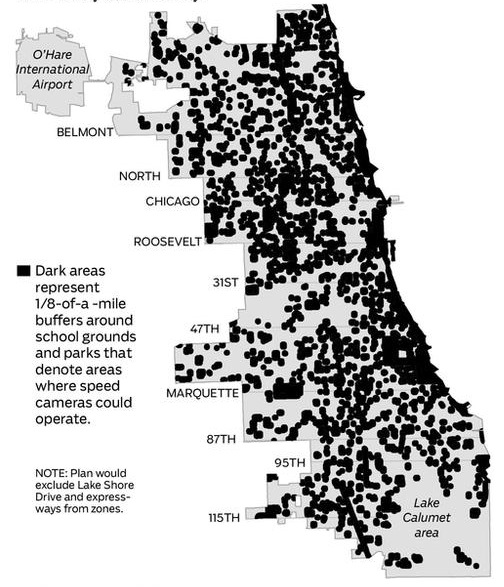

Chicago's speed camera bill is big, but it's also targeted. Cameras will only be permitted within one-eighth of a mile of a school or park. The cameras won't be allowed on highways or Lake Shore Drive. And the money raised from speed cameras, which could be considerable, will be spent on public safety initiatives near schools and parks, pedestrian safety, and infrastructure improvements.

That package of provisions helped blunt criticism that speed cameras are just a cash grab by Chicago, which emerged as the strongest argument against them. “The perception could not necessarily be a good one if it’s perceived that it’s just out to raise revenue, when actually what our intent should be is safety,” said Alderman Margaret Laurino, the chair of the Pedestrian and Traffic Safety Committee, last October. Laurino voted for the bill yesterday.

In part because of the tailoring of the bill, supporters of speed cameras were able to successfully focus the debate on the safety of children. "I mean, what do you say to a parent that's been there from the day their son or daughter was born, and they're killed by a speeding motorist next to their school, or their park?" asked Quinn when signing the bill.

New York's speed camera bill limits the number of cameras that would be allowed, unlike Chicago's, but doesn't specify where they could be used or dedicate the revenue to related programs.

Have Unified Control of State Government

Admittedly, this one might be trickier to pull off in the short term, but it's probably the secret to Chicago's success. When Mayor Rahm Emanuel (D-Chicago) took his speed camera proposal to the legislature, he was able to win as co-sponsors House Speaker Michael Madigan (D-Chicago), House Majority Leader Barbara Flynn Currie (D-Chicago) and Senate President John Cullerton (D-Chicago). The bill was signed by Governor Pat Quinn (D-Chicago).

The politics are a bit trickier in New York, where Mayor Michael Bloomberg, an independent in name but viewed as a Republican in Albany, faces skeptical Democrats in the State Assembly and suburban and rural interests in the State Senate.