New research from New York University's Furman Center [PDF] provides added evidence that New York's parking minimums are forcing developers to provide unwanted automobile infrastructure, leading to less development, higher housing costs and more traffic.

The new study expands on previous research from the Furman Center, extending the analysis from Queens to the other four boroughs and looking more closely at the process by which developers of smaller projects are exempted from parking requirements. The results show conclusively that parking minimums greatly distort the number of spaces built from what the market demands.

"Our findings suggest that the requirements generally cause developers to provide more off-street parking than they think buyers and tenants really demand," said Vicki Been, director of the Furman Center, in a statement. "The city has announced that it is reviewing its parking requirements. As that review is underway, it is important to explore how parking regulations might better balance concerns about housing affordability, sustainability, and traffic congestion, on the one hand, with the needs of car owners on the other."

Looking at every market-rate, residential development built between 2000 and 2008, the Furman researchers found 1,003 with more than five units (smaller projects are eligible for a waiver from the city's parking minimums).

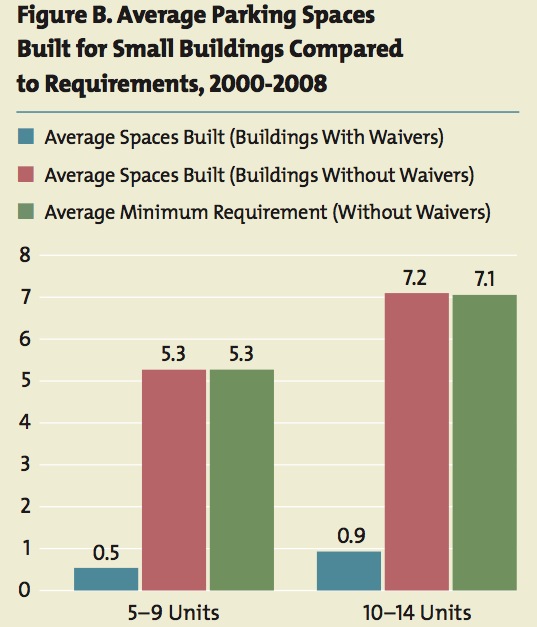

Of those, 68 percent leapt at the opportunity to avoid the mandated construction of parking, taking advantage of another waiver based on lot size. Most of those developers didn't just want to build less parking, they wanted to build no parking at all. Only 17 percent of those who took a waiver built a single parking space.

Where developers couldn't get out of parking minimums, most built only what the city demanded of them. Over three-quarters of projects subject to parking minimums built either exactly the number of spaces required or a tiny number more. Whatever your opinion of parking minimums, it's clear that they're doing their job: forcing developers to provide parking, even if no one wants it.

The effect, the report argues, is regressive, providing a benefit to an affluent minority of automobile owners. "Car owners are not a majority in New York City, but they are the primary beneficiaries of free on-street parking and the minimum requirements for new off-street parking intended to preserve access to that free resource," it reads. "The likely costs associated with this system, however, are borne by everyone -- traffic congestion, higher environmental impacts, and possibly higher housing costs."

In one East New York project targeted at families making less than $44,000 a year, parking requirements forced Dunn Developments to build 18 parking spaces for the project's 43 units. Only nine of the spaces are rented out. That means higher costs for all the residents. At its Navy Green project, Dunn won a mayoral override of parking minimums in order to keep rents affordable and a playground on site.

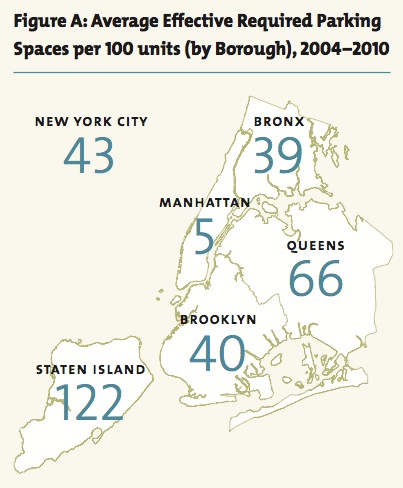

Calculating the true parking minimums for New York City is a difficult exercise, due to the multiple ways developers can avoid the requirement, so the Furman Center's new estimates of effective parking minimums in each borough is valuable. Given current lot sizes, the researchers estimate, 43 parking spaces are required for every 100 market rate housing units built citywide.

Almost no parking spaces are effectively required in Manhattan -- though where big lots were built uptown to satisfy parking minimums, they've been urban design disasters -- but 66 spaces are needed for every 100 units in Queens and 122 for every 100 residences on Staten Island.

Those figures don't account for the possibility of land owners subdividing their lots into pieces small enough to get around parking minimums, but as the authors point out, that itself is a costly distortion of the housing market. "Developers may reconfigure zoning lots to smaller sizes or unusual shapes to avoid parking requirements, and may then be unable to build the same number of housing units on the reconfigured lot than they would be allowed on the original lot," says the report.

Architect Richard Ferrara and developer Alan Bell have each told Streetsblog that they have subdivided projects, at a cost of either capital or housing units, all in order to avoid parking minimums.

Echoing previous research from the Furman Center, this report finds that parking minimums are lower, though still high, near subway and commuter rail lines. Because those areas are often zoned to allow higher density, however, they actually end up having more parking in an absolute sense.

The Furman Center report doesn't take a normative position on whether the costs of parking minimums -- less housing at higher costs, increased traffic and pollution -- outweigh the benefit of protecting incumbent drivers from competition for existing parking spaces. But it lays out in no uncertain terms that those are the stakes: some of New York's most pressing issues like affordable housing and environmental sustainability versus keeping parking cheap.

As the Department of City Planning moves forward with reforms of parking minimums in the city's "inner ring" of neighborhoods, it is pursuing a political strategy: moving quickly in Downtown Brooklyn, where developers strongly desire to eliminate the minimums, and proceeding elsewhere only as politically palatable. The Furman study should, hopefully, show politicians and communities just how costly their defense of parking minimums really is.