Independent auditors at the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have just released the results of their lengthy investigation of the Railroad Retirement Board, the federal agency that evaluates disability claims by commuter railroad workers -- and has historically approved more than 99 percent of them.

Photo: NYT

Photo: NYTThe New York Times obtained an early copy of the GAO report and quoted the Retirement Board's general counsel as admitting that internal reforms had not succeeded in slowing the growth of disability applications and approvals by rail workers, specifically employees of MTA's Long Island Rail Road.

A Times investigation revealed that LIRR workers -- even white-collar managers who had little active role in running trains -- had won approval for approximately $250 million in taxpayer-funded disability payments since 2000.

In fact, the GAO found that LIRR employees have filed Retirement Board claims at a rate 12 times higher than the other seven railroads covered by the agency (a list is available after the jump). Meanwhile, LIRR riders are facing yet more fare increases amid a massive budget gap at New York's transit authority.

How could the Retirement Board get away with sending disability payments to rail workers who the Times found well enough to spend most days golfing? By setting the bar for claims much lower than the Social Security system, which administers disability requests for most American employees.

The Retirement Board requires rail workers claiming a disability to have 20 years of work experience at any age level or 10 years, for those who have already turned 60. Social Security, by contrast, requires 20 quarters of participation in the system during the 10 years prior to the claim.

Once that standard is met, the Retirement Board asks workers to prove that they are prevented from working in their regular railroad position due to a permanent mental or physical condition. Most LIRR claimants provided their medical evidence of disability from one of three doctors, which the GAO deemed "an indicator of fraud or abuse."

Social Security, on the other hand, asks workers to prove that a permanent ailment prevents them from taking on any gainful employment in the national economy. While 99.6 percent of LIRR employees won Retirement Board payments, only 39.1 percent were approved for Social Security disability checks. Employees of other commuter railroads, who won 100 percent approval from the Retirement Board, were cleared by Social Security at a 79.4 rate.

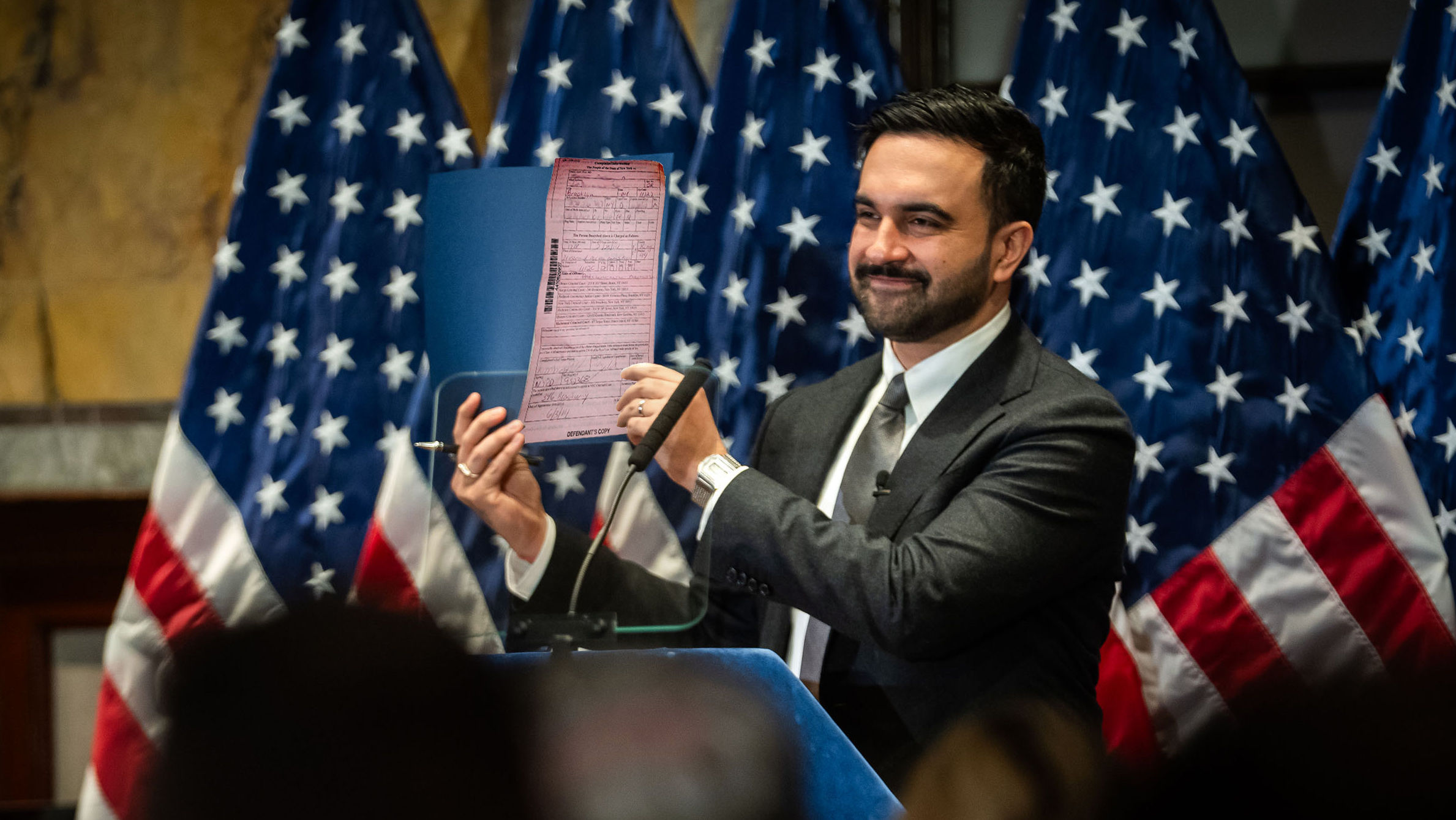

After the Times story prompted New York attorney general Andrew Cuomo to open a formal probe of the LIRR disability system, the Retirement Board implemented a five-point reform plan to apply greater scrutiny to rail workers' claims. But the GAO audit cast doubt on the plan's effectiveness, noting that a nearly universal rate of claims approvals has remained the norm. The Retirement Board defended the five-point plan and reiterated its commitment to better quality control.

Rep. John Mica (FL), the senior Republican on the House transportation committee, said in a statement that he had taken over supervision of the GAO request after an initial inquiry by Sen. Charles Schumer was withdrawn. "We should not assume that there

is widespread abuse of the program by railroad workers, but we need to

determine whether improvements to the system are necessary," Mica said in a statement.

In addition to the LIRR, the following railroads are covered by the federal Retirement Board: the Massachusetts Bay Commuter Railroad, Metro-North Railroad, New Jersey Transit, Northeast Illinois Commuter Railroad, Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District, Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation, and Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority.