As Mayor Mamdani appears set to move forward with his predecessor’s misguided 15 mile per hour Central Park speed limit, he should first consider the real problem the new rule is meant to solve. It is not reckless cyclists. It is scarcity.

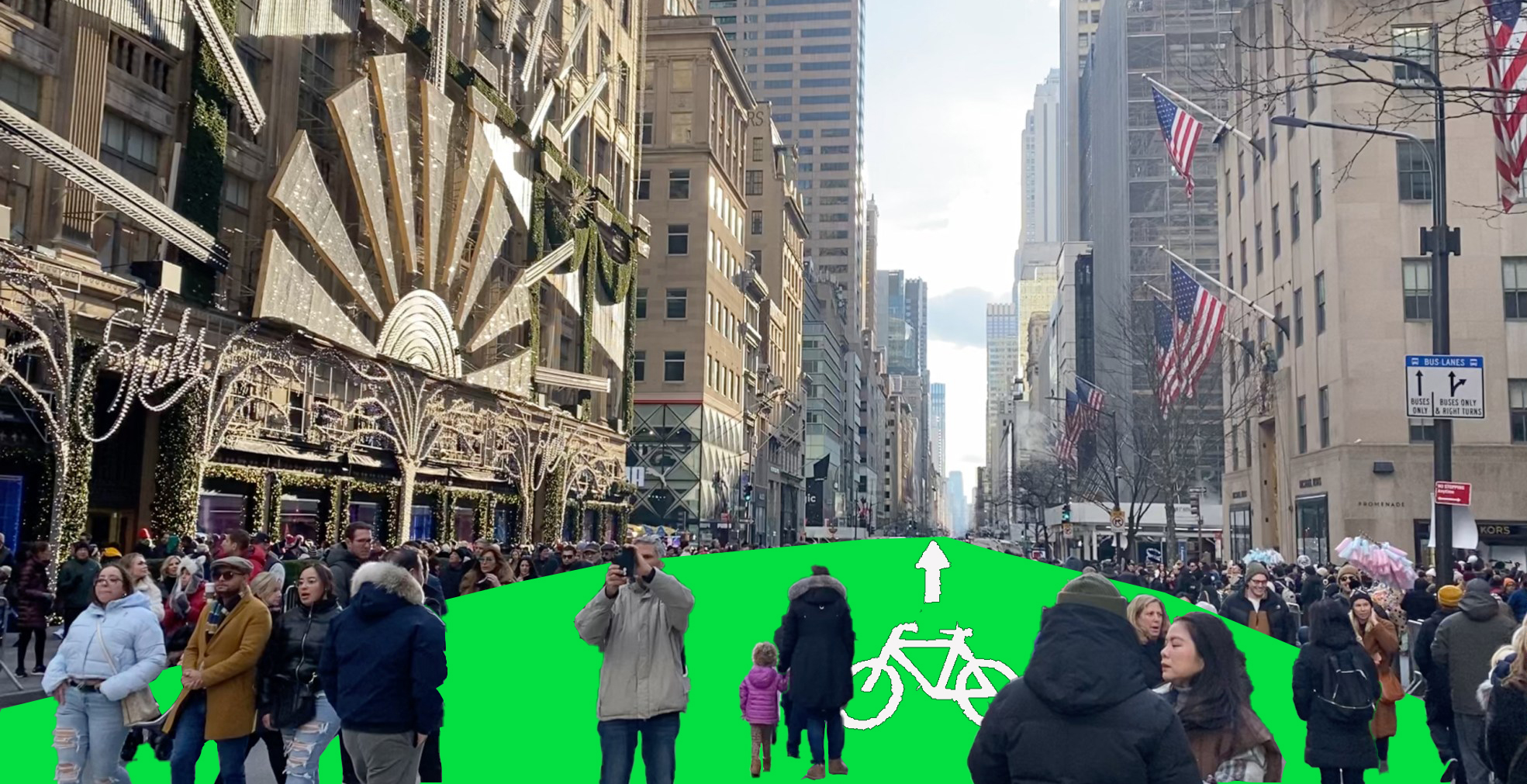

New York City has chronically underinvested in cycling infrastructure compared to its global peers. When too many users — walkers, runners, commuters, families, tourists, and athletes — are forced to share a single, finite facility, conflict becomes inevitable. Lowering the speed limit on Central Park Drive is an attempt to manage scarcity through restriction rather than solving it through investment.

The correct response is abundance: creating enough high-quality cycling venues, in and around Central Park and across the city, so no single facility is overstressed.

Consider that London, with a comparable population and geographic footprint, invested roughly $100 million in cycling infrastructure in 2025 alone. This continues a multi-year commitment to building out the network of cycleways connecting to its central business district. New York City has consistently fallen short of its own goals for building out protected bike lanes. Noble aspirations notwithstanding, we are still rationing space instead of building it.

In and around Central Park

Ironically, the city already knows what to do here. The 2024 Central Park Drives Safety and Circulation Study, commissioned by the Central Park Conservancy and written in part by new Transportation Commissioner Mike Flynn, offers a blueprint — one that remains largely unimplemented.

First, the city should move forward on recommendations to creating bikeways along the park’s transverses and adjoining roads. These would relieve pressure on the Drive while improving east-west mobility for cyclists of all abilities.

Second, actively encourage pedestrian use of the many arches spanning the Drive. The Greyshot Arch in particular provides an alternative to the congested crossing at W. 61st Street. Separating classes of users via graded crossings reduces conflict more effectively than blanket speed limits.

Third, the city should issue a request for proposals to grade-separate the signaled crossing by the Delacorte Theater, one of the most chaotic conflict points on the loop.

Finally, the Central Park Conservancy should consider permitting cyclists to access the Bridle Path. The path was originally designed for equestrians to ride at speed. With appropriate rules and stewardship, it could safely accommodate cyclists while relieving pressure on the main drive.

Create alternatives beyond Central Park

If the goal is to reduce cyclist-pedestrian conflict in Central Park, the city must give cyclists somewhere else to go. Here are some options.

The Departments of Transportation and Parks and Recreation should designate alternate venues for cyclists to train, including Randall’s Island, the Belt-Shore Parkway corridor, Jamaica Bay, Rockaway and Freshkills Park. Red Hook and Hunts Point — industrial areas that are largely empty on weekends — are also candidates.

The city must finally commit to upgrading the arterial connectors long sought by the NYC Greenways Coalition. Fragmented networks force cyclists into bottlenecks; connected networks distribute use.

The city should also consider a weekend recreational network that stitches together existing bikeways, residential streets, and industrial corridors that sit largely unused on weekends. My “Grayways” proposal adapts the East Coast Greenway model by mapping a citywide network of bike lanes, park paths and slow streets through bike-friendly legislation and GPS wayfinding.

As routes gain acceptance, targeted upgrades could follow, expanding access to more residents. Because these routes would rely mainly on low-traffic streets, they’d require less mitigation to achieve meaningful harm reduction than arterial roads.

Grayways would connect neighborhoods with limited green space to marquee destinations like Shirley Chisholm, Pelham Bay, Conference House and Van Cortlandt Parks, while also offering self-guided tours through historic neighborhoods. By incorporating local playgrounds as regular rest stops, Grayways would broaden the constituency invested in their care and upkeep.

Finally, the Economic Development Corporation, which oversees NYC Ferry, should emulate Metro-North and Long Island Railroad and allow increased bike capacity on early weekday service from Manhattan to the robust, scenic network of protected bikeways spanning Bay Ridge and Rockaway.

A choice about the city we want

The 15 mph speed limit in Central Park is a symptom of a deeper failure of imagination. Cities that lead in safety and livability do not pit users against one another in overcrowded spaces. They build enough space for everyone.

New York can continue to manage scarcity through restriction — or it can choose abundance through investment. Only one of those paths reflects the city we claim to be.