Want a sure-fire way to injure New Yorkers? Open a last-mile warehouse.

The e-commerce boom that began during the pandemic has led to a different kind of ailment in industrial neighborhoods with double-digit-percent increases in injury-causing traffic crashes near new last-mile warehouses, Comptroller Brad Lander charged in a report released on Monday.

Eighteen of the facilities opened since 2015 — 11 since 2020 — clustered in neighborhoods like East New York and Red Hook in Brooklyn and Maspeth in Queens. The majority of these sites — most of which are owned by Amazon – have made area streets more dangerous due to van and truck drivers dispatched through sub-contracted "Delivery Service Providers" that have been accused of skirting safety in favor of profit.

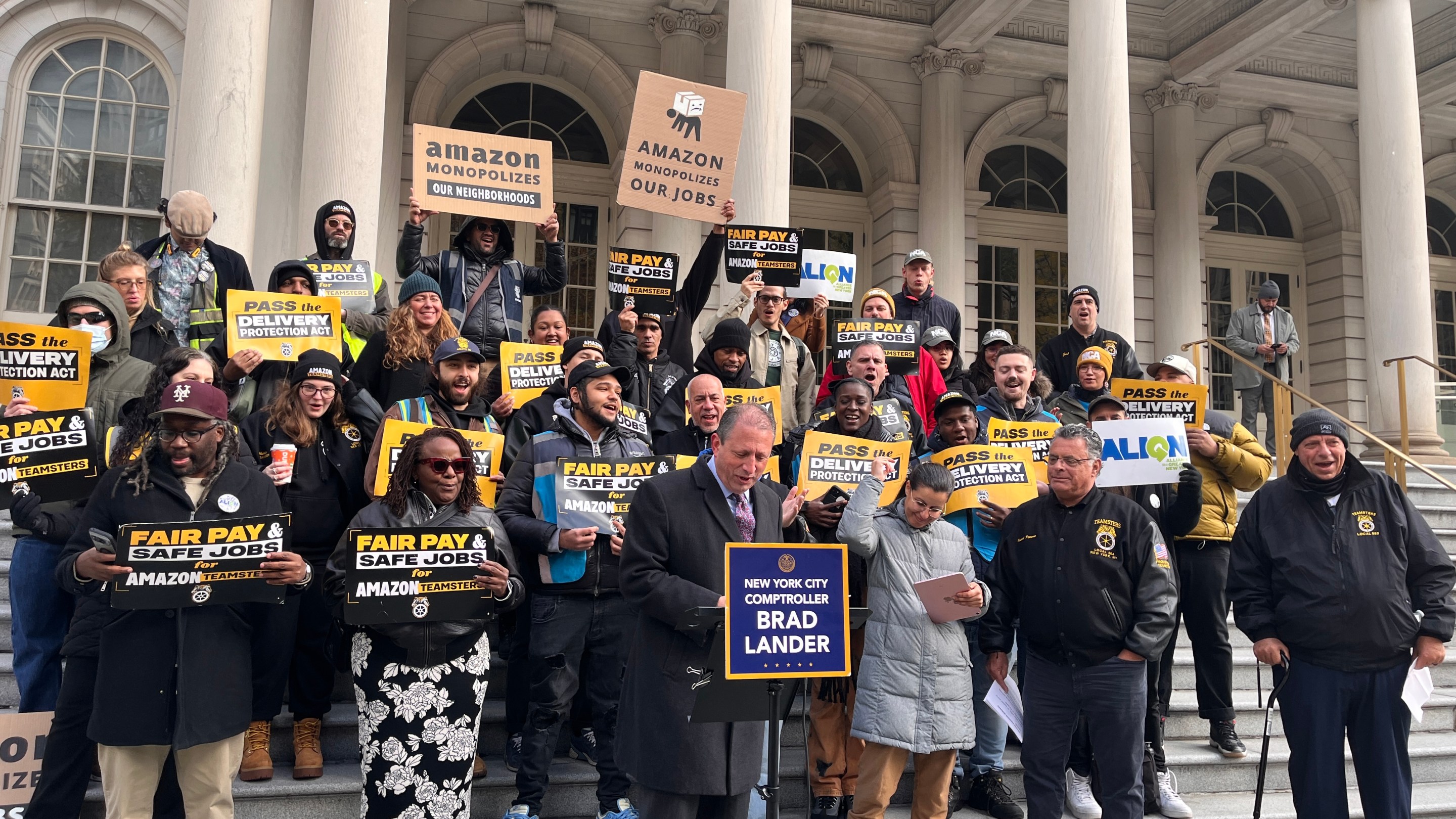

This is why, Lander argues, the City Council should pass the “Delivery Protection Act,” sponsored by Council Member Tiffany Cabán (D–Astoria), to force the e-commerce giant to directly hire its delivery drivers.

“We've become so accustomed to getting our toilet paper, socks, or butter cookies right away that we’ve stopped thinking about the consequences; but we all pay the price of more traffic crashes, worsening air quality, and worker injuries,” Lander said on Monday. “This report is a wake-up call: adopt reasonable regulations for delivery services or worsen street safety, environmental impacts, and workers’ rights. We cannot allow the benefits of e-commerce to come at the expense of limbs, lungs, and lives.”

There was an average increase in crashes of 10 percent in the streets surrounding 14 out of the 18 sites. Maspeth, Queens has fared the worst. In areas near its two last-mile facilities, crashes rose by 53 percent and 48 percent, respectively.

And truck-involved crashes show that these warehouses bring a whole new type of danger to an area. Within the same half-mile radius of the 18 sites, injury-causing crashes involving trucks grew by 137 percent.

The report used data from the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection to locate these facilities and link them to one of the few major companies facilitating e-commerce in the city. Twelve of the 18 warehouses are owned by Amazon, two by FedEx and UPS, and one each by CDL and OnTrac.

A coalition of advocates from the Teamsters, ALIGN, the Environmental Justice Alliance, and Transportation Alternatives, slammed Amazon for skirting responsibility for street safety with its subcontracting model.

Workers that the public sees making deliveries for Amazon, whether in a van, on a truck, or riding a bike, are not actually employed by the Bezos-founded company. Instead they work for a "Delivery Service Partner." Caban’s bill, Intro 1396, is meant to end this practice in favor of direct employment.

The confusing system allows Amazon to skirt responsibility for its massive delivery operations. DSPs pop up and close down easily, repeatedly forcing delivery drivers out of work, advocates say. DSPs at Amazon’s Maspeth warehouse, the one where injuries in the surrounding area increased by 48 percent, unionized under the Teamsters last year and workers have been sounding the alarm on the link between the precarious employment model and street safety.

“Every day I show up ready to work and everyday I face safety issues,” said Latrice Johnson, a member of the Teamsters and a DSP employee delivering from Amazon’s Maspeth warehouse. “We are being rushed to meet impossible quotas, we skip breaks, we hold our bathroom needs for hours, we push our bodies past what is reasonable because Amazon treats us like machines, not human beings.”

Another Maspeth driver, Luke Albert Renee, who has been with his DSP for three years, said he often is forced to drive vans with broken mirrors.

“Amazon keeps claiming one thing, that safety is their main priority, but me and my other coworkers over here know it’s a lie,” he said at Monday’s presser.

DSP workers have consistently called out issues of high turnover, where whole work forces can be fired and replaced on a dime, putting inexperienced drivers on the road.

“And then came the layoffs,” said Johnson. “Over 100 drivers were gone, with no warning, no respect. Families like mine were left scrambling. … Amazon replaced reliable experienced drivers with brand new, inexperienced workers. And you know what that means? More accidents, more stress, more danger for workers and our entire city.”

The report argues that a direct employment model would fix the problems cited by Johnson, Renee and their fellow workers. If Amazon has to directly employ its drivers, it would be incentivized to reduce the chance of crashes, instead of just prioritizing speedy delivery, because the company would be liable, the report said. Cabán’s bill also requires robust safety training for drivers, something Amazon DSP workers have testified is lacking currently.

The company disputes this, citing its safety investments and telling Streetsblog last month that over the past year it has seen a 32 percent decrease in "behaviors like speeding and distracted driving," but have not shared where that number comes from.

The company also slammed the report as incomplete and accused it of being "designed to reach conclusions from the start."

"Our metrics demonstrate meaningful safety improvements, reflecting our ongoing commitment to investing in advanced safety measures that protect our workforce and the communities where we operate," company spokesperson Dannea Delisser told Streetsblog. "All of our facilities are located in areas zoned for industrial or commercial activity by the city and operate in full compliance with city laws and regulations. We hold both Amazon and our partners to high safety standards and continue to invest in safety enhancements and innovations.”

The bill currently has 37 sponsors, a veto-proof super-majority of the 51 member body, that span the political spectrum. There has not yet been a hearing on the bill, but supporters want to see it passed by the end of the session, with just one more stated meeting left to get it done.