Amazon's workers don't actually work for Amazon nor do they spew forth every morning from Amazon warehouses — and a Council bill seeks to change that.

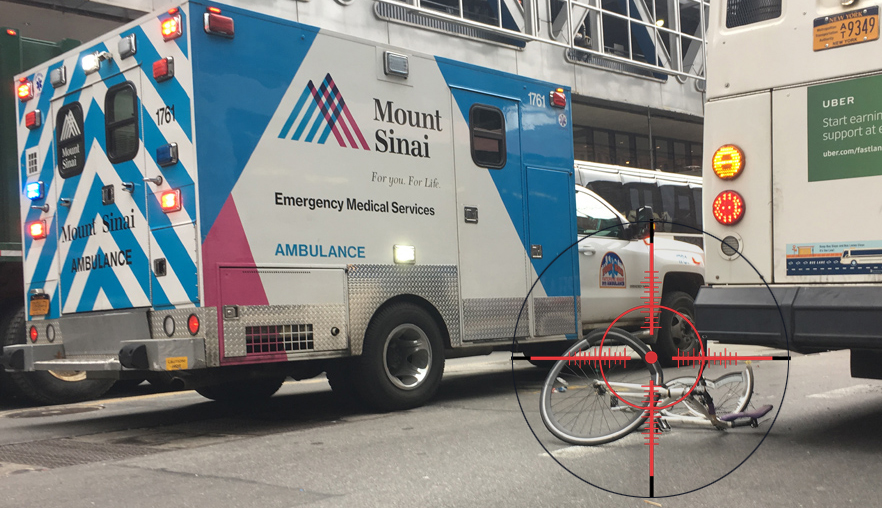

Currently, Amazon-branded trucks and electric cargo bikes are actually sent out across the city by a network of Amazon subcontractors or "Delivery Service Partners." But this way of doing business is a subterfuge, and as a result “last-mile” facilities run by Amazon subcontractors with very little oversight end up being packed into just a few neighborhoods, bringing pollution, traffic violence, and safety risks.

And Amazon, the company profiting the most, is not held accountable.

A bill to be introduced on Thursday by Council Member Tiffany Cabán (D-Astoria) would require delivery companies — like Amazon — to directly employ their drivers, ending the "Delivery Service Partners" model.

The bill will also mandate safety training, make the companies directly responsible for driver safety, and require "last-mile" delivery centers to be licensed with the city. If passed, the new rules would be enforced by the underfunded Department of Consumer and Worker Protection.

The legislation is supported by The Teamsters, Amazon Labor Union, National Employment Law Project, The Alliance for a Greater New York and the Retail Workers Union.

“This legislation is going to remove the veil from these subcontractors and put the onus on Amazon as a corporation for protecting its workers,” said Theodore Moore, the executive director of the Alliance for a Greater New York, which has been fighting Amazon's worker abuses for the better part of a decade.

Regulating the last mile

The mayor's City of Yes for Economic Opportunity rezoning brought into the public eye how last-mile delivery centers, which are often Amazon DSPs, deliver negative effects on the communities that surround them, such as increased pollution and traffic. Part of the final agreement for the sweeping rezoning aimed to boost the city's economy was a promise from the administration to regulate these warehouses.

Another bill, Intro 1130 by Council Member Alexa Avilés (D-Sunset Park), seeks to regulate the pollution of these facilities by proposing an "indirect source rule," which requires warehouses of a certain size to pollute less through a series of weighted options, some of which would get large dangerous and polluting trucks off the streets.

The city has yet to begin an environmental impact study of this legislation, which is needed before bringing it to a vote.

A spokesperson for the city Department of Environmental Protection told Streetsblog that the agency has "procured, contracted, and onboarded consultants who have started market research that feeds into the analysis." The agency expects to launch the formal process this fall, which takes a year.

Shifting responsibility

But the second layer to the last-mile problem has to do with labor conditions, which is what Cabán's bill seeks to address.

Nationally, warehouse and package delivery workers had the highest rate of serious injury among private sector industries in 2022, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Amazon has already shifted much of its deliveries in the five boroughs to electric vans, four-wheel electric cargo bikes, and personal cars through it's Amazon Flex app. But the workers you see delivering your Amazon package work for a DSP.

Amazon has over 4,400 DSP's nationwide, and defines the companies as "independent delivery organizations that help Amazon deliver thousands of packages to customers every day. DSP delivery drivers are employed by individual DSPs (not Amazon)," the website reads. Many of the facilities appear to the outsider as Amazon buildings, with logos and the like.

The DSPs are technically independent, but labor experts say that Amazon should be considered a joint employer due to the control the company exhibits over DSPs.

"Amazon insists that its DSP delivery drivers are not Amazon employees. But they deliver Amazon packages, in Amazon trucks, wearing Amazon attire, and their work is tightly controlled by the company," according to a National Employment Law Project report. "Amazon determines the daily routes drivers are assigned to, the number of deliveries to be completed each day, and delivery deadlines, while communicating this information directly to drivers through an app."

When individual DSPs unionize — like in California, Georgia, Illinois, and New York — Amazon just cuts ties with the DSP and finds another one to take its place. But since the DSPs are separate companies, Amazon argues that it can't be held liable for union busting, since the workers don't technically work for them.

The workers at Amazon's DSPs often report having to use vans that are in bad condition, having to complete hundreds of deliveries in a short timeframe and resorting to peeing in bottles for fear of being late. This incentivizes reckless driving and illegal parking.

"You have these delivery drivers and warehouse staff that are pushed to meet impossible quotas, they work long hours for low pay, they suffer high rates of serious injuries. And because companies like Amazon hide behind fake shell companies and subcontractors they really dodge all responsibility for these unsafe conditions," said Moore.

By shifting the responsibility to Amazon, instead of spreading it through the subcontracting companies, advocates say the bill will improve conditions on the street by increasing accountability.

“When we are all making purchases around Black Friday or prime day, they need to push those things out, which leads to drivers not being as cautious as they would normally be, because they know they have to deliver these things within a certain amount of time," said Moore. "I think people need to know that there is a price to pay for convenience."