The first week of congestion pricing bucked the years-long trend of increased bridge and tunnel traffic into Manhattan's Central Business District, initial crossing data show.

Morning commuter times last Wednesday, Jan. 8, dropped year-over-year on every bridge or tunnel into the tolling zone below 60th Street, the MTA told reporters on Monday — with an average drop of 34 percent between the eight crossings.

Numbers analyzed by Streetsblog buoy the MTA's rosy assessment: The number of vehicles in the Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn-Battery tunnels — which with the exception of the hardest years of the pandemic have trended up since 2018 — dropped significantly in the first five weekdays of the new toll compared to equivalent period last January.

The Queens-Midtown Tunnel hosted 199,057 vehicle crossings in the first five weekdays of the new toll — 6.6 percent fewer than last year and 5.3 percent fewer than 2018.

"It certainly seems like this is a step-change differences. This is not just a small incremental reduction the way the last 10 years have seen small incremental increases," said MTA Deputy Chief of Policy and External Relations Juliette Michaelson. "It has been a very good week here in New York. There’s less traffic, quieter streets — and I think everybody’s seen it."

The MTA on Monday presented initial data from the first week of the toll — with the caveat that conditions will likely evolve as time goes on — that showed 43,000 fewer vehicles entering the congestion relief zone compared to the baseline of the previous three years, a drop of 7.5 percent.

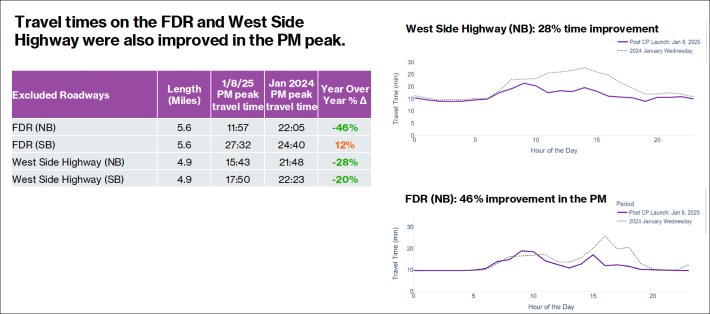

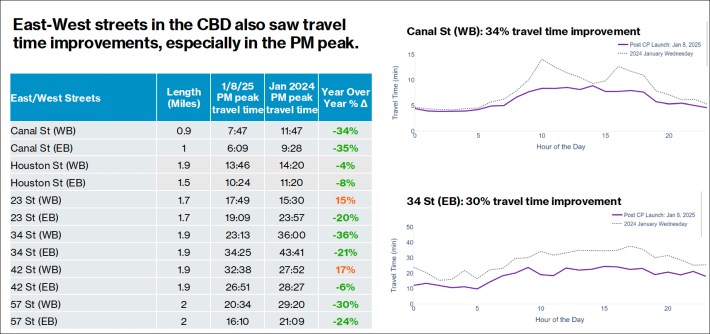

The "greatest improvements" were on the inbound river crossings, but travel times also dropped on most east-west two-way crosstown streets, some north-south avenues and the FDR Drive and West Side Highway in the evenings, which border but are not directly within the toll zone, the MTA said.

Some avenues — Second, Fifth and Ninth — experienced 1-percent increases in travel times, which MTA and city officials attributed to construction or other conditions unrelated to the new toll.

Buses have also seen "consistently high trip-time reductions," largely thanks to lighter traffic on the bridge and tunnel river crossings, officials said.

The B39, which traverses the Williamsburg Bridge, had a 28-percent drop in travel time. Travel times on the SIM24, which goes from Staten Island through New Jersey and the Lincoln Tunnel into Manhattan, dropped 5.3 percent, or nearly four minutes, thanks entirely to faster travel times through the tunnel.

"We’re seeing buses moving faster, especially in the morning peak," Michaelson told reporters. "The buses are benefitting from those reduced trip times on the East River and the Hudson River, particularly our express bus routes that utilize those crossings.

"This is great news for our express bus riders. It's also great for New Jersey Transit riders," she said.

Contrary to the New York Post's specious claims that public transit has been "packed" because of the toll, "the effects of drivers switching to transit are muted," Michaelson said — with the exception of a slight increase on some express bus routes, possibly because of the improved travel times.

Even then, those buses remain well below the level of ridership that would require turning away passengers.

(Further defying The Post's anti-congestion pricing campaign, the city Department of Transportation has not seen any evidence of drivers parking just outside the toll zone and getting on transit to avoid paying the toll.)

A DOT official on hand for Monday's press briefing used the example of the daily backup on the Williamsburg Bridge to illustrate the toll's initial impact: Typically, Manhattan-bound traffic on the ridge backs up all the way to to the bridge tower on the Brooklyn side; since congestion pricing launched, the line of cars doesn't even reach the tower on the Manhattan side.

MTA officials did not say on Monday how much money the $9 peak toll had raised to fund the authority's sorely needed capital investments. Those estimates should be available in a matter of weeks, not months, officials said.

But the much-ballyhooed specter of toll scofflaws covering their license plates may have been overstated: Crossing data from the Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn-Battery tunnels crunched by Streetsblog showed no increase in the number of drivers without an EZPass — indicating that the new toll had not resulted in any increase in illegal license plate activity.

Congestion pricing's impact on the Manhattan streetscape and regional traffic in general has been easy to spot for New Yorkers driving, walking, biking or taking transit into and within the Central Business District — as evidenced by the MTA's numbers. The initial results inspired confidence for transit advocates.

“Seeing is believing, and the numbers don’t lie – these axioms are proving true as data comes in after the first week of congestion pricing," said Lisa Daglian, executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA, an advocacy group.

"Take a walk or ride into Midtown. There is ... less congestion, easier street crossings, and a sense of muted surprise from even the most jaded New Yorkers. The changes we’re seeing in just one week border on epic, and it’s just the beginning of a better future for our region."

One caveat to all the good news is that experts also predict a slight rebound in traffic once drivers see that they are getting a good value for the toll.

With reporting by Dave Colon