Congestion pricing’s absurdly prolonged gestation has another victim: Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, one of the policy’s most incisive supporters, won’t be marking the Jan. 5 arrival of the tolls in the New York Times. Krugman, a twice-a-week Times columnist for a quarter-century, penned his farewell column last week.

I had been looking forward to Krugman’s take on the big day, not just because he’s a fellow economist and, thus, strongly inclined toward congestion pricing, but because Krugman the columnist delighted in exposing the illogic of people in high places ― powerful politicians and billionaires alike ― and tracing it to their insularity or greed.

For evidence, look no further than Krugman’s July 24, 2023 column, An Act of Vehicular NIMBYism, starting with his cinematic lede:

At 7:50 a.m. on Monday, July 24, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey reported that cars driving east through the Lincoln Tunnel to Manhattan were taking 30 minutes to make the crossing, compared with only seven minutes earlier that morning. According to the authority, traffic was actually “light” compared with normal: The tunnel has limited capacity, so during the morning rush, cars always back up on the infamous Helix, the corkscrew approach to the tunnel.

Now he puts you in the picture:

If you choose to drive into Manhattan during that rush, you add to that backup. You probably add only slightly, maybe less than a second, to the delay facing each driver behind you — but there may be thousands of people in the queue, so the total cost you impose, in wasted time and fuel, is substantial…

Then he brings the hammer — the cost of the delays you impose by driving into Manhattan:

And of course, the congestion you create by driving into the busiest part of Manhattan is just beginning when you’ve exited the tunnel. Your presence slows city buses, the taxis and other for-hire vehicles that make up more than half of Midtown traffic, the delivery trucks that keep the city’s economy functioning. In short, when you drive into New York, you’re imposing large costs on other people. And I mean really large costs. Reasonable estimates suggest that taking a private car into Manhattan during the morning rush and back out during the evening rush creates congestion costs of well over $100 — and if you think about it, especially while stuck in the traffic jam at the Helix, numbers that big seem entirely plausible.

In that column, Krugman didn’t just portray driving into Manhattan as the choice it is, he asked motorists to see that each such choice “imposes large costs on other people.” And he attached a price tag: a triple-digit figure, backed by my modeling, that cast the $9 to $23 toll range as the bargain it is.

The coup de grâce was the column’s venue: not an East River bridge or 60th Street but the New Jersey entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel. Befitting Krugman’s holistic habit of thought, his target wasn’t hapless motorists, but New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, who three days prior had sued in federal court to block the sole proven antidote: congestion pricing.

Murphy’s lawsuit, which remains the leading threat to the program, was a thinly disguised ploy to force the MTA to share some of the congestion revenues. To highlight the suit’s hollowness, Krugman smartly pointed to the “hundreds of thousands of New Jersey residents [who] commute into New York by train or bus and … would gain from reduced congestion after they arrive.”

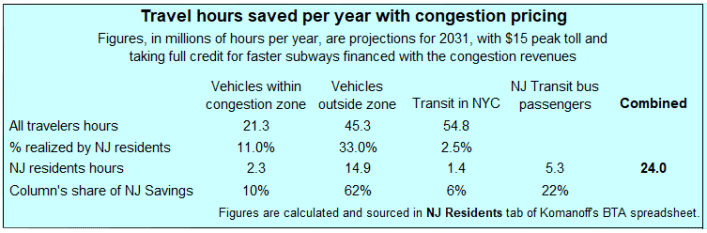

Yet the total time that NJ residents will be saving once congestion pricing reaches full flower is many times greater than their time savings just within the congestion zone, as this table shows:

That table accompanied my op-ed last month in the Newark Star-Ledger, Gov. Murphy’s congestion pricing vendetta harms New Jerseyans. In that post, I pointed out that dividing Jersey residents’ annual tolls, an estimated $180 million by their 24 million hours saved with congestion pricing yields an average price tag of $7.60 for each hour of saved time. That cost per hour saved is half of the state’s $15/hour minimum wage. Considering that the typical regular New Jersey car commuter to the congestion zone earns well over $100,000 per year, per Krugman, those motorists will be getting a very good deal despite paying the congestion toll.

Moreover, the table’s bottom row shows that over half of NJ residents’ total prospective time savings will occur on their home state’s tributary bridges, highways and tunnels ― a byproduct of the general thinning of road traffic headed to and from the Manhattan congestion zone. In other words, hundreds of thousands of Jersey drivers who rarely or never venture into the city will benefit as literal “free riders” enjoying but not paying for smoother commutes.

The same goes for drivers in the Hudson Valley, Long Island and the city’s “outer boroughs” ― a central element of congestion pricing that has been altogether lost on the program’s opponents.

Krugman’s column ran nearly a year-and-a-half ago. Beneath its trenchant headline, he confessed to being baffled that “affluent progressives who more or less cheerfully accepted the extra taxes that helped pay for Obamacare and donate generously to social causes … seem to lose it when someone proposes allowing more housing construction or a much-needed power transmission line anywhere near their residences.”

Krugman speculated that “even people who are socially conscious about big things … lose all sense of proportion in the face of suggestions that the way they live their own lives is problematic and might need to change, even slightly.”

“Something strange is going on,” Krugman wrote. Actually, opposition to congestion pricing isn’t at all strange to those of us who for years have had to battle to make even the slightest headway for livable, less-car-dependent streets and cities. “Car brain,” we call people’s fanatical attachment to their automobiles. Or, in urbanist @big_pedestrian’s memorable formulation of car brain on Twitter, “the deeply held belief among many motorists that anything less than everything is an injustice.”

Happily, NIMBYism writ large appears to be losing its chokehold. Just last week, Times editorial writer Mara Gay celebrated NYC’s “City of Yes” pro-housing re-zonings with New York Democrats Begin Saying No to the NIMBYs. That was in regard to housing, of course, but a broader rejection of NIMBY objections to urban transit reform and clean energy siting may not be far behind.

Krugman the columnist has exited, but beginning on Jan. 5 his legacy, along with that of scores of pro-congestion pricing visionaries back to Bill Vickrey and Arthur Pigou, will glow even more brightly.