The driver who drove backward at high speed into a renowned educational reformer will avoid prison for the fatal crash by participating in a course designed to let killer drivers learn the impact of their recklessness, Streetsblog has learned.

The deal will allow Jorge Gonzalez-Cadme to plead guilty to a serious, but rare, charge of criminally negligent homicide, but receive three years of probation on the charge by completing Brooklyn DA Eric Gonzalez's "Circles for Safe Streets" course.

More critically, he will not have to give up his driver's license as part of the deal.

A spokesman for Gonzalez said the arrangement had the blessing of the family of Norm Fruchter, the giant of education who was killed by a reverse-driving Gonzalez-Cadme on Dec. 22 on quiet 68th Street in Bay Ridge, cops said. Fruchter's widow confirmed that she did not want jail time for Gonzalez-Cadme, but declined to comment further.

Some street safety advocates were initially buoyed when Gonzalez charged the driver with criminal negligent homicide, a low-level felony that the DA has previously said is difficult to sustain in front of a jury of driving peers. The charge carries a maximum of four years in prison, but district attorneys have said they are reluctant to prosecute killer drivers on that count because they believe jurors will consider a fatal crash just "an accident."

Indeed, in the crash that killed 7-year-old Dolma Naadhun in Queens in 2023, DA Melinda Katz initially sought criminally negligent homicide, but backed off and offered probation to killer driver Claudia Mendez-Vasquez, also claiming to have the support of the victim's family.

"There still is a reluctance by New York prosecutors to treat traffic deaths at the hands of a motorists the same as a death committed by another instrumentality," said personal injury lawyer Daniel Flanzig. "The fear is that potential jurors view the action of the driver as a 'bad choice,' but not criminal in nature."

Another lawyer who often represents victims of car crashes focused mostly on the fact that Gonzalez-Cadme will retain his driver's license.

"I have mixed feelings about utilizing the criminal justice system to hold reckless drivers accountable — except that driving is a privilege not a right, and reckless drivers should lose that privilege for at least some period of time, if not indefinitely, depending on the offense," said lawyer Adam White.

The deal in Brooklyn still requires a sign off from Judge Christopher Robles, who suggested at a hearing on Monday that he'll need some convincing.

"Somebody died here, so I need a little bit of information," Robles said from the bench. He asked several times if Fruchter's family consented to the no-jail deal, but also wanted to know if the family would participate in the Circles program, whose benefit, supporters say, is maximized when killer drivers are forced to sit with the family of the person they killed.

"Part of the program is that the defendant would have to meet with the family?" Robles asked.

Gonzalez's assistant district attorney Jessica Wishart said that it is not clear if Fruchter's family will participate because that's "optional." If family members don't participate, a stand-in can be appointed to recount the family's pain to the killer driver.

The criminal justice system has been struggling to both rein in reckless drivers, but also find non-carceral ways to do it.

In 2021, Gonzalez started collaborating with the Center for Justice Innovation on the Circles for Safe Streets program, a restorative justice model aimed at showing reckless drivers the impact of their dangerous habit.

After sessions with drivers and people they have killed or injured someone (or a surrogate), the driver must write a one-page reflection on how the one-day session will prevent them from committing further harm with a deadly vehicle.

But the program is limited: For one thing, many defense lawyers don't want their clients to participate because admitting guilt in a criminal trial comes back to haunt them in a civil case.

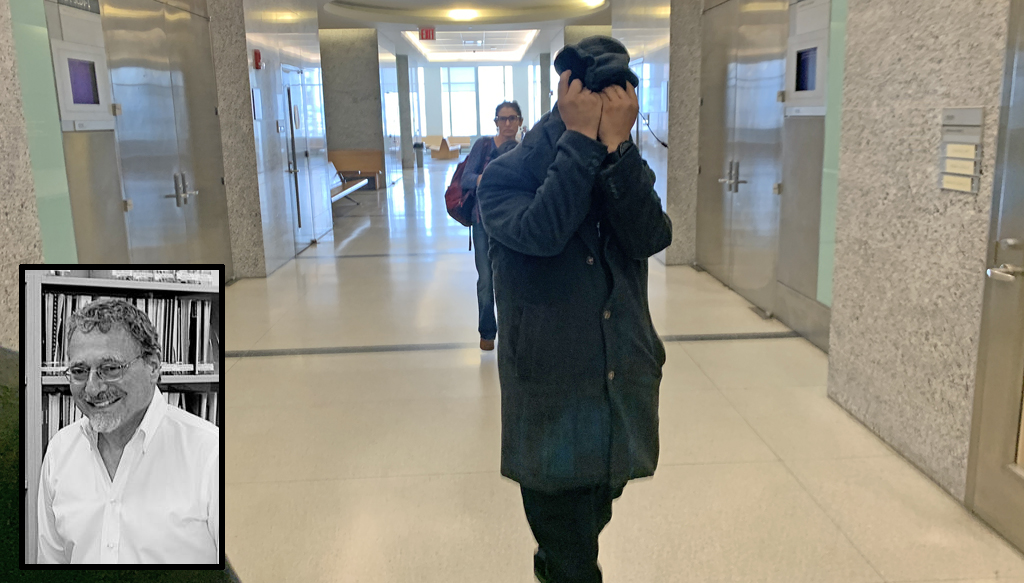

Indeed, Gonzalez-Cadme will be pleading guilty to the criminally negligent homicide charge under this deal. (He and his lawyer declined to speak to a Streetsblog reporter after the hearing on Monday.)

A spokesman for the Brooklyn District Attorney said the program is growing, but shows initial promise because participants have not reoffended.

Why punishment matters

Every death robs society of a valuable member, but that is especially true in the case of Norman Fruchter, who was a leader for progressive education in New York.

“Norm Fruchter was a giant, a pioneer, and the consummate advocate for equity and fairness,” Pharoah Cranston, a spokesman for NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, said at the time of Fruchter's death. The educator was a senior adviser at the center after a 60-year career in education that included a stint on a community school board in Brooklyn and leading the Ford Foundation’s national dropout prevention program.

Fruchter was also a novelist, publishing “Coat Upon a Stick” in 1963 and “Single File” in 1970.

Streetsblog contributor Charles Komanoff was stunned by Fruchter’s death, given how deeply he was involved in bike safety advocacy when Fruchter's first wife, Rachel Fruchter, was killed in Prospect Park in 1997.

“They were progressive royalty — Norm was a renowned and beloved figure in education scholarship and advocacy and Rachel was a renowned and beloved health researcher and practitioner,” said Komanoff. “Her death became a rallying point for street-safety advocates.”

Even years after her death, Rachel Fruchter — an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the SUNY Health Science Center in Brooklyn and a contributor to the landmark “Our Bodies, Our Selves: A Book By and For Women” — was frequently evoked by street safety advocates as they called for the removal of cars from Prospect Park.

That effort was successful. But car drivers still kill more than 200 people and injure close to 50,000 every year. Very few are convicted — and those that are rarely suffer any punishment that becomes a deterrent to other drivers. There are reasons for that.

"It's hard to tell what acts better as a deterrent: jail or license suspension," Flanzig said. "In a city and state with car dependency, loss of license or vehicle forfeiture works well."

But seizing vehicles is exceptionally rare, except in cases where drivers have committed other crimes, such as drunk driving, Flanzig added.