He's tossed himself into the valley of political death.

Purely for political and self-serving purposes, Mayor Adams is attacking congestion pricing — and, in doing so, is undermining the implementation of a program that he has long claimed to be a "strong" supporter of.

Hours after he raised questions about the proposed $15 peak congestion pricing toll, Hizzoner was at it again on News12 on Thursday night, as the New York Times's Dana Rubinstein tweeted from the official mayoral transcript:

Last night on News 12, @nycmayor put a lot of political distance between himself and NYC’s incoming congestion pricing scheme pic.twitter.com/YmmjAjpVye

— Dana Rubinstein (@danarubinstein) December 1, 2023

That followed his earlier comments in an interview with Streetsblog when Hizzoner said that the “$15 proposal "is the beginning of the conversation" and that we must "hear from communities ... and make a determination of who is going to be exempted" from the toll.

What's wrong with the mayor raising concerns about impacted communities or urging a new "conversation" on exemptions and pricing? In this case, a lot. And it all gets back to what Swedish transportation official Jonas Eliasson once famously called the congestion pricing "valley of political death."

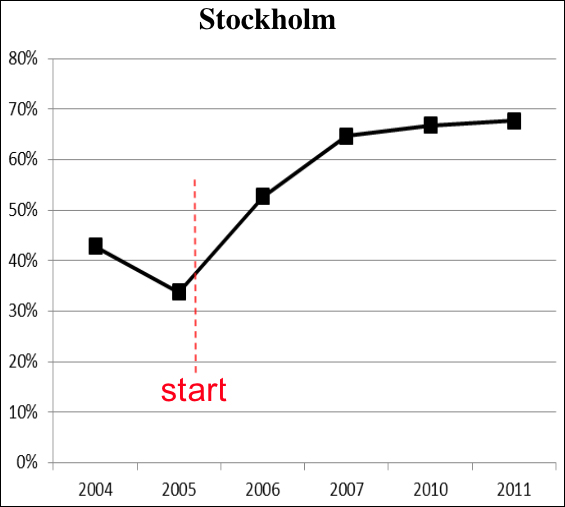

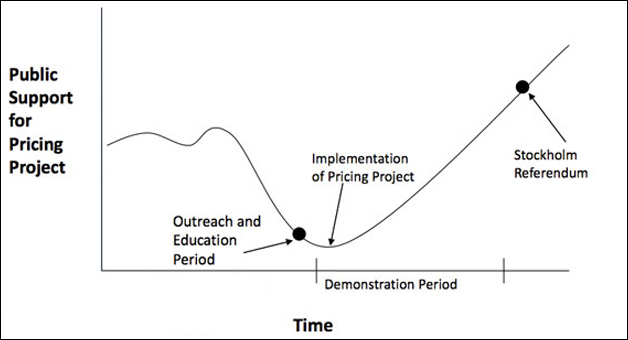

As history shows from Stockholm (but also other cities where tolling was established), before congestion pricing starts, there is a predictable hue and cry by a small minority of drivers who will pay the toll because of their personal choice to drive and to contribute to the congestion all drivers will suffer in a particular zone. And then politicians, never the bravest of thinkers, amplify that driver anxiety (because politicians are almost entirely drivers), which causes a dramatic dip in public support.

Of course, once congestion pricing launches — and the benefits of reduced traffic, faster trips, more funding for transit, fewer road deaths and, yes, less pollution are realized — support goes way up.

Stockholm is a perfect test case because its congestion pricing scheme — launched in 2005 — was followed shortly thereafter by a public referendum on whether to keep it or scrap it. In that resolution, congestion pricing passed with 70 percent of the vote, as you see in this other Eliasson chart:

Our colleague Clarence Eckerson spoke to Eliasson a few years ago about this political dynamic — and why it's so important for politicians to get it right before implementation begins.

"Congestion pricing in Stockholm started off as a very politically controversial thing — no one really believed that people would like this," he said. "Once the charges were in place, and the benefits were so great and so visible, public support grow from something like 25 or 30 percent to 55 percent for the referendum. And once the revenues were used ... for bicycle lanes, for bus lanes, for pedestrian use ... support has grown to 75 percent."

Eliasson said Swedes went through exactly the same craven debate the mayor is seeking to create, with local politicians defending the people who "have to drive" into the congestion zone, even though studies show that very few New Yorkers "have to" drive into the most transit-rich part of the city.

"We also had this debate about how car drivers don't have any choice but to drive," he said. "But once the charges were in place, just overnight, roughly 20 percent of the car trips disappeared. ... Just 20 percent makes traffic look like a vacation period rather than rush hour. Twenty percent less traffic is roughly the difference between a very calm Sunday morning and rush hour. So it really made a huge difference. And we've never had the same debate ever since because congestion pricing just works. It will free up road space and free up road space, which means less congestion. And then you will get money which you can spend in various ways.

"Once it is in place and once you see the benefits," he added, "then a quite large share of the population says, 'OK, maybe this was a good idea after all.'"

Instead, our mayor is being a mayor and not a leader, congestion pricing advocates say.

"The mayor is a politician, and politicians wake up every day and think, 'What's good for me politically today?'" said traffic expert Bruce Schaller, a city official under Mayor Bloomberg. Schaller said he's been listening to the mayor's comments without concern because the city leadership has no control over congestion pricing, but he does wish the mayor would be focusing his concerns on how to best implement congestion pricing, rather than suggesting that the way it's being undertaken is, as he put it Thursday, "a big mistake."

"It would be fair for the mayor to say, 'This fee should be higher' or 'This should be lower,' but instead, he's being vague and that only stirs the pot of opposition. If you're a big supporter, don't talk like this."

On the merits, Schaller, who specializes in taxis, said the mayor is just flat-out wrong about the negative impact congestion pricing will have on cabbies. "It is going to work out for yellow cab drivers because of the reduction in traffic," he said.

Study after study after study confirms that the mayor is flat-out demagoguing that issue: taxi rides will increase because faster vehicle speeds will make hailing a cab a better value, even with the added fee. As Charles Komanoff recently reported, congestion pricing will push out enough car traffic to create 7 percent more taxi trips.

What about the mayor's concerns about city employees who drive into "the city"? Again, that's just demagogy.

"Maybe the only people who still call Manhattan 'the city' are the last ones to drive there," said Danny Pearlstein of Riders Alliance. "The other 85 percent of Manhattan-bound commuters take public transit." (It's also worth noting that Streetsblog's own investigation revealed that a huge percentage of people who "have to" drive into Lower Manhattan are merely members of the placard elite, whose driving is enabled by free parking.)

The mayor also raised issues about possible environmental effects on The Bronx, which were identified by the MTA, which says it will spend tens of millions to mitigate the slight increase in truck traffic along the Cross Bronx Expressway. The mayor ignored that mitigation effort and the larger truth of congestion pricing: It will improve the environment, even in The Bronx, not soil it.

Pearlstein, who lives in breathing distance of the Cross Bronx, isn't worried.

"I am confident that the mitigation measures are not only sufficient, they're overdue investments that were not otherwise being made, including by City Hall," he said.

Overall, he joined Schaller in thinking that Adams was displaying poor leadership.

"Hundreds of hours of broadcast media and at least as many column inches have been devoted to the gripes of the small minority of people who drive into Manhattan and their sympathizers," he said. "On behalf of millions more just like us, thousands of public transit riders have devoted thousands of hours to bring congestion pricing to the brink of implementation. The community has spoken and continues to speak. Now more than ever, we need the mayor to champion the transformative potential of congestion pricing, not to raise spurious doubts or amplify cynics and trolls."

Certainly, it's not like the current mayor is displaying less courage than others. His predecessor famously was cool on congestion pricing until he suddenly wasn't. And the chair of the Council's Transportation Committee, Selvena Brooks-Powers has also fed red meat to the tiny portion of her constituency that drives into the congestion pricing zone, saying that a $15 toll "to get into some of the critical parts of Manhattan is going to put definitely a hardship on many of my constituents."

If it were only true! Unfortunately for Brooks-Powers, the Tri-State Transportation Campaign famously debunked such concern for southeast Queens drivers before congestion pricing passed the state legislature in 2019, showing that fewer than 3 percent of residents of Brooks-Powers's neighborhood would be affected by the congestion pricing toll — while 100 percent of her constituents would benefit from any improvement in transit that congestion pricing promises.

I reached out to City Hall for an explanation of what the mayor is doing with this talk of reopening the congestion pricing debate, and after initial publication of this story, the press office got back to me, pushing back on some concerns.

The bit about city workers needing to be exempt from the toll, a spokesperson said, was specifically about city workers who are on the job in city cars. The spokesperson also said that the mayor is encouraged by the MTA's environmental mitigation in The Bronx. And the spokesperson all said that the "conversation" that the mayor referenced was merely a reference to the ongoing public comment period for the $15 proposal. In other words, nothing to see here?

I don't think so. I think that instead of clouding the water, Mayor Adams should be channelling another great New York political thinker: candidate Adams. Here's what that guy said before he was mayor:

This is what happens when the MTA makes bad spending decisions for decades. We need congestion pricing $ ASAP to protect stations from street flooding, elevate entrances and add green infrastructure to absorb flash storm runoff. This cannot be New York. https://t.co/F6A5K4ahQT

— Eric Adams (@ericadamsfornyc) July 8, 2021

Gersh Kuntzman's Cycle of Rage columns are archived here.