Red Hookers launched a new push for a direct bus to Manhattan from their peninsular enclave, calling on transit officials to provide better public transportation for the subway-less nabe — but an MTA official said that there's already too much "congestion" in the area to add a bus.

Officials have considered a bus link between subway-less Red Hook and Manhattan since at least the 1990s, and local civic organizers want the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to follow through on that idea, especially as the transit agency reexamines the borough’s bus network.

“Thirty years of waiting for a bus is long enough,” said Dave Lutz, a member of the Red Hook Civic Association.

The civic group penned a letter to officials last month urging them to implement a route through the Hugh Carey Tunnel, which already carries eight MTA express bus routes (none of which makes a stop in Red Hook). Such buses cost $7 a ride, while the Red Hook advocates are pushing for a regular $2.90 fare for a local bus.

The only public transit in Red Hook is two bus routes to Downtown Brooklyn, the B61 and the B57, both of which can slow to walking speed due to heavy congestion, and riders still have to transfer to a train to continue their trips to Manhattan.

The closest subway stop is at Smith and Ninth streets on the F and G line, about a 20-minute walk away and a long climb up its steps and escalators to the platforms of the highest-elevated station in the system.

Experts have said that MTA and city officials are not offering enough transit improvements ahead of congestion pricing, which will charge drivers to enter Manhattan below 60th Street, compared to other cities like London, which ramped-up bus service in tandem with its central business toll 20 years ago.

“So what are we getting for congestion pricing?” Lutz asked. “It takes us 20 minutes to get to the subway by foot, or you take the B61 and you sit in traffic on Columbia Street — those are our choices.”

In recent years, the MTA has been slowly working on a borough-by-borough revamp of its ancient bus networks, which in some sections date back to early 20th-century trolley lines.

In its Brooklyn draft plan released in December, the agency suggested two new routes in Red Hook: the B81 extending to Prospect Park and south to Midwood and the B27 connecting to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but there are no proposed new lines to Manhattan. The agency expects to release a final plan some time next year.

Now is as good a time as any to include a Manhattan-bound route, said Red Hook state Sen. Andrew Gounardes.

“The people of Red Hook really deserve this,” said Gounardes. “I’m happy to roll up my sleeves and do whatever I can to try to make this happen.”

Ancient history

Proposals date back at least to the Giuliani administration in 1994, when Community Board 6 drew up a “community regeneration” plan, signed off by the City Council and the City Planning Commission two years later.

“To better link Red Hook with Manhattan, the MTA should immediately establish regular-fare bus service from Red Hook to lower Manhattan via the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel,” reads the 29-year-old document, referring to the name the tunnel had at that time. “Red Hook is easily accessed by vehicles and poorly accessed by all other modes of transportation.”

There used to be five routes in the neighborhood up until 2009, when officials reduced service due to budget cutbacks, according to a 2014 transportation study of the neighborhood by the Department of City Planning

That report went into further detail and recommended that MTA’s New York City Transit division study extending an existing bus line from Lower Manhattan via the tunnel, either as a regular route or as a peak-hour shuttle.

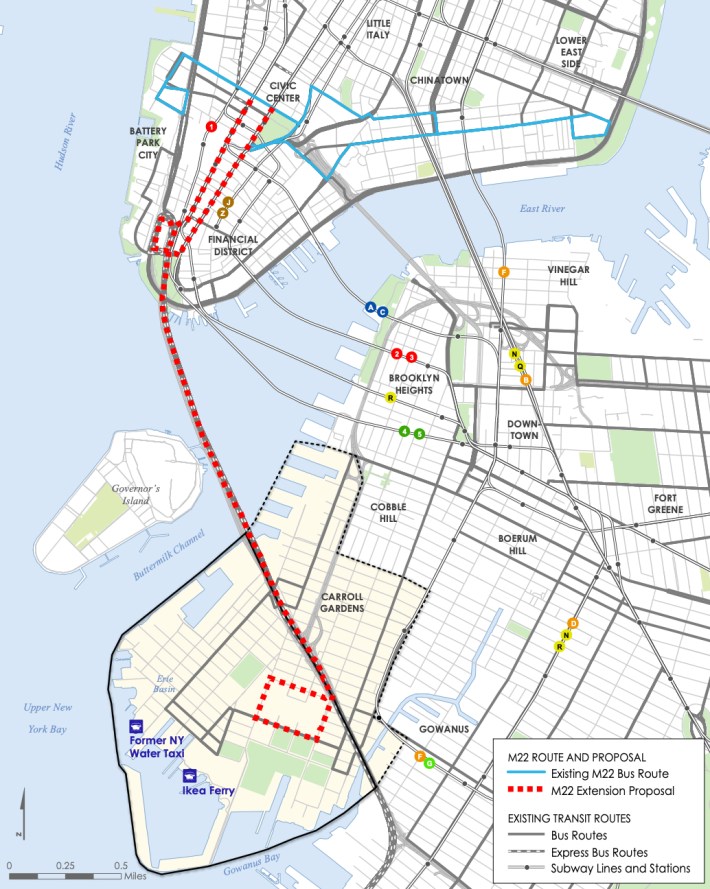

The city planners proposed extending the M22, which travels crosstown between the Lower East Side and Battery Park City.

Here’s what that would look like:

DCP suggested cutting the line’s lower ridership western portion near Battery Park City and rerouting it down Broadway to the tunnel and on to Red Hook, where the line would loop around the large public housing developments and the ballfields in the neighborhood. The new Brooklyn straphangers would likely make up the difference in passenger numbers, the planners argued.

MTA officials at the time rejected the idea, citing “prohibitively high” costs, few places to pick up passengers, adding that redirecting the Manhattan portion would be “challenging.”

Local advocates and politicians in 2017 tried to rally the MTA to restore the defunct B71 bus route connecting Red Hook to Crown Heights, which it had discontinued amid low ridership and budget cuts in 2010, and add an extension to Lower Manhattan.

The MTA's shrug

Now, an MTA spokesperson claimed that “congestion challenges” in the tunnel and in downtown Manhattan made it more “efficient” for Red Hookers to transfer from a bus to a train — even though the closest train, the F, doesn't go to Lower Manhattan. The 4 train does serve the Financial District, but it can only be caught all the way at Borough Hall, a long bus ride from Red Hook.

“Given congestion challenges in the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel and in Lower Manhattan, it is more efficient for customers to connect to the subway to get to Lower Manhattan,” said Joana Flores in a statement. “Improving connections between buses and the subway system is one of the MTA’s priorities when redesigning a borough’s bus network.”

The MTA previously trotted out traffic in Lower Manhattan as a concern when Brooklynites lobbied to bring back the B71 bus six years ago, the area's then-Council Member Brad Lander said at the time.

Great to learn that Red Hook neighbors are organizing around this effort again!

— Kathy Park Price (@KathyParkPrice) October 23, 2023

Led by then CM @bradlander, @JoAnneSimonBK52, Karen Blondel and others, a bus from Red Hook to Lower Manhattan was part of our campaign to bring back + expand the B71 bus route. #B71plus #b71orbust https://t.co/0gWOjoDUxk pic.twitter.com/roOYEcrFCu

However, buses would transport far more people taking up less space than individual cars, and congestion pricing is slated to reduce traffic in the central business district zone below 60th Street by between 15–20 percent, according to MTA’s estimates.

"We’re talking about the boundary of the congestion pricing zone where congestion should be improving within a matter of months," said Danny Pearlstein, the policy and communications director for the advocacy group Riders Alliance. "Bad traffic is not an excuse for not improving bus service, it’s an impetus for decongesting the street."

The MTA also sets the tolls for the Carey Tunnel, so if there are too many private vehicles using the crossing, officials could always adjust the charges.

"The tunnel is sort of the luxury option if you don’t want to sit in traffic," Pearlstein added. "But if the luxury is too affordable, maybe it’s time to jack up the price."

Rejigging an existing bus route would also not break the MTA’s bank, said Gounardes.

“Adding a new bus line [or] tweaking service is not tens of millions or hundreds of millions of dollars,” Gounardes said. “This is a smart targeted thing we could do that would have a big impact.”

Public support

MTA Chair and Chief Executive Janno Lieber has long called buses the “engines of equity” for their predominantly working-class riders.

The overwhelming majority of Red Hook residents live in the expansive New York City Housing Authority complexes of Red Hook East and Red Hook West, and many would benefit from a more direct way to travel into Manhattan.

“That’d be a real good thing,” said Red Hook resident Gregory Russell as he waited for a B61 bus outside the NYCHA complexes on Lorraine and Columbia Streets Friday.

The Brooklynite noted that a bus would also make it easier for people with disabilities than relying on the subway system, where only 27 percent of stations are fully accessible via elevators and escalators.

“I got a bad back. Just being able to get on one bus and being able to get to my destination, that would be excellent,” said Russell.

Another resident in the adjacent micro-neighborhood known as the Columbia Street Waterfront District said she stopped using the B61 because it gets stuck in traffic on Columbia Street.

Many drivers use the road as a cut through coming off the BQE — a spillover effect of the city reducing the highway’s triple cantilever to two lanes each way in 2021 without following expert advice to also restrict access to local on ramps to deter those kinds of shortcuts.

“During rush hour now [the bus] barely moves, so I basically don’t take it anymore,” said Lotta Hagman, who makes a longer walk to the ferry or the subway.

A direct trip to Lower Manhattan would shave off a lot of her commuting time for job at the United Nations, whose East Side headquarters are within sight from her rooftop — but a long trip away by mass transit.

“Even though I can actually see work from here, it takes me over an hour,” she said.