So, about that cargo bike revolution...

Leaders in the freight industry say that proposed city rules to regulate transporting freight by bike will not only destroy the one sector of the business that is currently working well, but will also choke off some innovation for the foreseeable future.

After Streetsblog broke the news that the city was promulgating new rules to — hopefully — spur innovation, industry leaders began widely and loudly condemning the proposal. The worst part, they say, is a clause in the rules that would cap all pedal-assist cargo bikes and trailers at just 10 feet in length — a proposal that would prohibit all of Amazon and Whole Foods' successful and popular cargo bike delivery wagons.

"The 120-inch cap is going to eliminate all bike-and-trailer cargo solutions that currently operate in the market today and in the future," said Ben Morris of Coaster Cycles, one of the leading manufacturers of cargo bikes for the industry. "It will eliminate all the progress that has been made over the past few years. It would take us backward.

"This rule, if put into effect, would eliminate the primary solution that operates in New York City today," Morris continued. "Many of the stakeholders were very surprised to see the rules written as such. It's never been discussed. Why put that in there?"

To better make his point, Morris sent over a picture of one of his company's cargo bikes — a model he called "a reasonable solution and currently working in the marketplace" that would nonetheless be barred because it is 178 inches from front wheel to the back of the trailer.

Streetsblog interviewed six other industry leaders and many had the same reaction, though none would go on the record. Amazon declined to comment publicly, but several of the manufacturers who build Amazon's trailers said the company will strongly protest the rule change at a hearing next month.

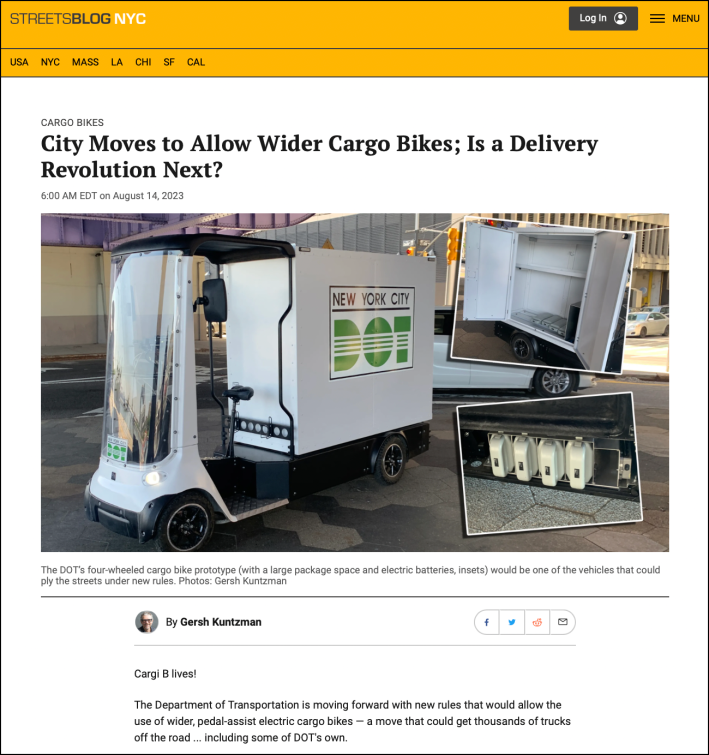

The main thrust of the rules proposed by city Department of Transportation is to allow the use of four-wheeled, pedal-assist van-like cargo bikes, which some believe are illegal under state law because of the fourth wheel. Another state law clarifying the matter is stalled, prompting DOT to act, the agency said.

But several freight operators said that DOT is acting to help the owner of a company that just happens to make a large, four-wheeled cargo bike — the very same bike that the DOT is testing.

Those bikes are made by Fernhay, which is owned by a well-connected lawyer, William Wachtel. Unlike other freight operators, Wachtel supports the rule change — and not only, he said, because it benefits his company.

"I believe that the landscape of the city of New York has to change in order to accommodate e-bikes, cargo bikes and the like, and it's got to be done thoughtfully," he told Streetsblog. "As much as people have wanted to increase sustainable transportation, there has to be more planning. And it isn't easy; this is uncharted waters. But now's the moment to step back and figure out how to do it right. It's hard to get a mulligan when it comes to things like this."

Wachtel's four-wheel bike, despite looking bulky, is 36 inches wide and just under 10 feet long. Existing cargo bikes and trailers in the industry are longer and, more important, wider, which can create conflict in bike lanes. The DOT rules would allow for bikes up to 48 inches wide, something that many industry leaders don't think is so great.

The Amazon/Whole Foods trailers are 14 to 16 feet long, so they would be barred under the new rules. And that's what industry leaders can't understand.

"One-hundred-and-twenty inches?! That's 10 feet!" said one industry leader who asked for anonymity because he works with the city. "I don't know what's behind this. It's arbitrary and capricious."

The biggest flaw in the rules is how it would destroy the successful Amazon/Whole Foods operation, said another industry leader.

“I applaud the efforts of the DOT to increase the width of cargo e bikes/trikes and four-wheel modalities to 48 inches, but the suggested limit of 120 inches will force us to shut down, completely reengineer our operations or return to using vans for delivery,” said Mark Chiusano, CEO of Net Zero Logistics, an industry leader in the tri-state area and Boston.

"Between the bike/trike, hitch and trailer we need at least 16 feet to operate effectively," Chiusano added. "The limit of 120 inches will decimate our productivity as well as the earnings of our employees by reducing the amount of freight/groceries with each route performed. While we all agree our objective is to reduce our carbon footprint, the only way to gain the lost capacity with the 120-inch restriction is to return to a van operation. I am confident that is something no one wants to see happen."

DOT strongly denied that it would wipe out Amazon and Whole Foods' operation overnight.

“DOT’s goal is to increase the adoption of safe, sustainable delivery modes — and the proposed rule would allow for the continued use of popular cargo carriers on the street today while expanding options for companies," agency spokesman Vin Barone said in a statement. "The proposal serves as a starting point and we look forward to feedback from the freight and logistics industry and members of the public.”

It is not uncommon for proposed rules to change after more feedback is provided by the industry.

And many companies experimenting with four-wheel cargo bikes, not just Fernhay, especially in Europe. Barone added that there are many existing bike-and-trailer models that are shorter than the proposed 10-foot limit, which is accurate on paper, though very few of those models are on the street right now.

The DOT rules would also bar electric-assist trailers, which is another area that industry leaders said they hoped to move in the future.

Former DOT official Jon Orcutt, now with Bike New York, focused on the agency's failure to get out of the way of innovation.

"It's a terrible way to write the rules," he said. "You need the rules to look ahead and say, ''What is going to be on the street in five years, not now?'" he said. "Let's not use the rules to choking ourselves off."

Industry leaders who were not Wachtel believe that the well-connected lawyer has some undue influence over the Adams administration — though such speculation is common when one company's design is chosen over others'. And Wachtel, like many others, has been pushing cargo freight for years.

Wachtel and his law firm, Wachtel Missry, are not big campaign contributors, but Wachtel's law partner, Morris Missry, is on the board of the city Economic Development Corporation — and that position led the city to hastily abandoned a planned helipad contract for Wachtel's Saker Aviation division after the Daily News reported on the apparent conflict-of-interest earlier this year.

Wachtel denied any influence over the DOT rule-making process, and DOT pointed out that many companies are currently manufacturing four-wheel cargo bikes that meet the DOT's proposed rules.

All of which makes the Sept. 13 public hearing on the matter uniquely crucial. One industry source said he believes that the DOT

"DOT is going to hear from everyone, but they are good and their hearts are in the right place on this," said Martin Rahmani of The Hub Bicycles. "We think they're going to listen."

UPDATE: After initial publication of this story, Jeff Holmes, a spokesman for the city Economic Development Corporation issued the following statement:

“Due to circumstances involving changes in the permitted uses of the Downtown Manhattan Heliport and the availability of federal funding to facilitate waterborne freight deliveries, it is in the best interest of the city to re-solicit the RFP for an operator at the Downtown Manhattan Heliport. Furthermore, after investigating allegations of conflicts of interest, we found no merit to the allegations. The RFP selection and concession approval process is governed by FCRC rules and the NYCEDC board has no involvement in this procurement.”

The DOT's lone public hearing on the matter is on Sept. 13 at 10 a.m. on Zoom (click here). If you are asked for a password, it is 658250. Those who can't make the hearing, but still want to comment have these options:

- By web by clicking here.

- By email by clicking here.

- By snail mail by writing to Diniece Mendes, NYC Department of Transportation, 55 Water St., sixth Floor, New York, NY 10041

- By fax by using the old-fangled machine, dialing 212-839-7777, and hearing this historic tone: