Last week in this space I inveighed against a downtown neighbor for putting an anti-congestion pricing plank in her City Council campaign platform. The candidate, Susan Lee, is convinced that that the congestion toll will deter customers, hurting local businesses, especially in Chinatown.

Two days after my post went up, I saw a chance to assess Lee’s claim. I had booked a lunch date at my go-to Chinatown eatery, Great N.Y. Noodletown (recently included, at Number 37, in the New York Times’ list of NYC’s 100 Best Restaurants). I decided to show up early and ask customers coming in or out how they had arrived.

To be sure, small-business owners viewing their customers through a windshield lens is a classic trope in livable-streets circles. One such instance, reported in Streetsblog in 2018, involved Ben’s Best, a deli on Queens Boulevard in Rego Park that shuttered that year. The owner, Jay Parker, ascribed his shriveling sales to tougher customer access caused by the new bike lane, ignoring changes in neighborhood demographics and cultural tastes that have killed off four-fifths of the city’s Jewish delis since the 1930s.

(By the way, the Queens Boulevard bike lane scapegoated by Parker is the very lane I used on Easter Sunday to safely bike a dozen miles further east to Casa Margaritas, a fantastic new Colombian restaurant on Jericho Turnpike in Bellerose. Highly recommended!)

Similar scaremongering sought to stop a proposed car-free busway on a short strip of Main Street in Flushing, bike lanes in Sunnyside, a busway in Jamaica, a car-free bus route through Greenwich Village and too many other projects to even list here.

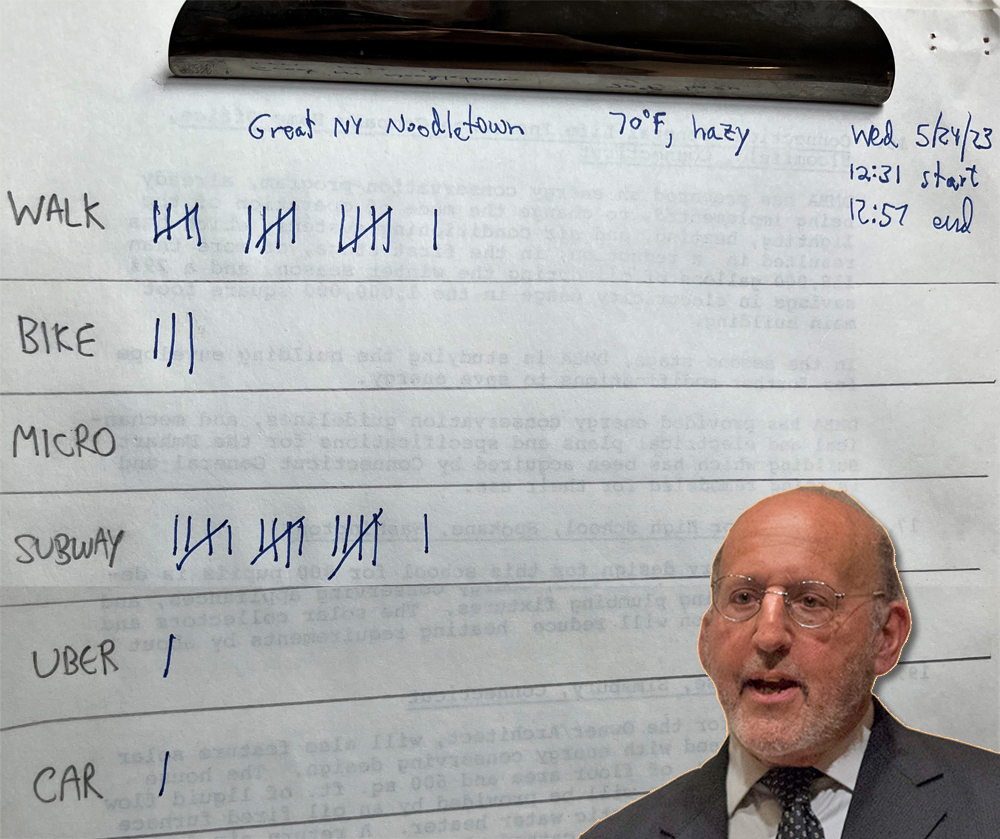

With this history in mind, last Wednesday I stuck a sheet of paper in a clipboard, marked it off with eight rows — walk / bike / micro-mobility / subway / bus / cab / Uber / car — and pedaled to the corner of Bowery and Bayard Street. In 26 minutes outside Great N.Y. Noodletown I garnered 37 replies, summarized in the graph. (I missed a dozen or so other customers, due to my inattention or language limitations.)

As the graph shows, just two of the 37 respondents came to the restaurant by motor vehicle (one in their own car, the other in an Uber). Three people, or one more than those, said they came by bicycle. Interestingly, two of those three asked why I was collecting the data — the only ones to do so. Both of them quickly grasped my point and pronounced themselves fans of congestion pricing. (Nothing in my demeanor or clothing gave away that I, too, had biked there.)

To be sure, my sample is slim. It might also be biased against autos, which probably get greater relative use in evenings and on weekends. Still, the percentages belie the notion that commerce in Chinatown invariably shows up in private cars or for-hire vehicles — the latter of which already pay a congestion charge that may not rise much anyway when congestion pricing starts next year.

My modest survey notwithstanding, no one knows exactly how much each city business depends on car or cab traffic, or, more important, can predict with certainty whether businesses will flourish or wilt if driving is made more costly or cumbersome, and other modes are made easier. But there is ample evidence that bike lanes, for example, improve business by enabling more spontaneous drop-in visits that car drivers simply would not make.

A vote from Team Flourish arrived in an email after my week-ago post, from Lower East Side resident and frequent Chinatown visitor Weiben Wang:

They open Mulberry Street in Little Italy to pedestrians every weekend and it's thronged with people. I can only imagine that it's because it's good for the restaurants. How can anyone believe that narrow streets clogged with cars are good for business? The one time I saw Mott Street opened, it was full of people strolling, relaxing, kids playing, community groups with tables, so much more pleasant than the usual unholy scrum crammed on the sidewalk. And I'll bet that the shops and restaurants did gangbuster business.

Amen. Be wary, then, when drivers and their allies prate about the dependence of shops and restaurants on auto traffic. It’s hard for business proprietors, who typically drive to their shops and finagle free or sub-market-rate parking, to identify with patrons who arrive on foot, via transit, or by bicycle.

And they certainly can’t picture the betterment that awaits once the bus lane, bike lane or congestion toll is finally in place. Like the hulking SUV parked at the corner, the present is hard to see around. Let the daylight in.

Charles Komanoff is a frequent Streetsblog contributor and renowned expert on traffic modeling.