Congestion pricing — now with bulk discounts!

The MTA will reduce congestion pricing tolls on low-income drivers who travel frequently into the Manhattan congestion zone, Streetsblog has learned — one of a handful of new mitigation efforts that are revealed in the final environmental assessment that was approved by the federal government on Friday.

For the first five years of congestion pricing, drivers using E-ZPass who have a household income of under $50,000 per year, or are enrolled in an income-based assistance program such as SNAP, will get a 25-percent discount on each trip into the congestion pricing zone after they've taken 10 trips in a calendar month.

Only about 9 percent of car commuters into Manhattan below 60th Street have incomes that meet the discount threshold vs. 79 percent of lower-income commuters who use transit, the MTA said in its draft environmental assessment. But the final EA offers the 25-percent discount because some low-income drivers have no "reasonable alternative," as the agency terms it, to drive into Manhattan frequently. As such, the MTA said it has to do something to avoid "a disproportionately high and adverse effect" on those drivers.

Under state law, congestion pricing has two goals: To raise $1 billion per year for public transit and to reduce congestion (and its attendant harms) in central Manhattan. The MTA tested several scenarios, with peak hour fees ranging from $9 to $23 per day, depending on the number of credits and exemptions the MTA offered.

The final EA also says that the toll during overnight hours will be at least half of whatever the peak hour toll rate is set as — and the lower-income volume discount will not apply to that. The hard-working laborer who "has" to drive into lower Manhattan for work has been a favorite example of congestion pricing opponents like Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-Cars), who in February mentioned that an ironworker son-in-law of a constituent drives to Manhattan every morning because he supposedly works too early to take public transit.

One longtime congestion pricing advocate said that the discount plan was a reasonable idea, especially since there are ultimately so few low-income drivers headed into Manhattan's central living area.

"The low-income discount is excellent in my opinion," said congestion pricing scholar and traffic analyst Charles Komanoff. "I like it more than my once-a-month freebie idea, which I wrote about in part simply to stimulate discussion. This one is both more targeted and more generous, since after all, if we advocates believe the numbers we've been trumpeting showing relatively few low-income regular drivers to lower Manhattan, then we have to also believe that the revenue loss and congestion-mitigation loss from the discount will be slight. And I do believe that."

In addition to the low-income driver discount, the final EA also said that taxis, including Uber and Lyft, will be charged at most once a day. The question of how often, if ever, taxi and high-volume app-based drivers would have to pay the toll has been one of the big issues facing the MTA and has even at times driven Uber to turn its fire on the policy which its executives swear they support. Taxi riders currently pay a $2.50 surcharge for every trip taken into or below 96th Street in Manhattan, and Uber/Lyft customers pay a $2.75 fee on every trip in the five boroughs, both of which go towards the MTA's capital fund, a policy put in place when congestion pricing was first passed and pitched as a first step in the program.

Drivers don't want to charge more, but one expert said that it's too early to see what the final EA's taxi policy will mean because it's unclear how it will all work.

"I'd like to see the details ... and how and who will ultimately pay and how [the toll] is calculated and collected," said Bruce Schaller, a former DOT official and expert on the taxi industry. "Taxis and for-hire vehicles just don't operate like a personal vehicle, so until those are spelled out it's hard to say this is good, bad or otherwise."

Schaller said the MTA would still need to figure out how to handle, for instance, how a driver is charged for passing 60th Street if he or she doesn't have a customer in the back. Ultimately, Schaller said that rule makers should place the onus on the passenger, not the driver.

"You want the passenger to pay, because from a policy perspective, you want the passenger to have the same disincentive not to come in by motor vehicle as a person would have not to drive their own car in. I'm assuming the passenger will pay one way or the other, but drivers are obviously concerned about that for good reason," he said.

Because the new mitigation efforts changed some of the inputs for the toll, the MTA said it created a new scenario — Scenario B2 — and modeled even bigger changes to see if this scenario would still accomplish congestion pricing's two goals: money and fewer cars in Manhattan.

The scenario includes the once-a-day cap for taxis plus "an entirely free period from 12 a.m. to 6 a.m. for all vehicles, including trucks," the agency wrote, going much further than the aforementioned 50-percent overnight discount between midnight and 4 a.m.

Even in this scenario, the MTA raised $1.07 billion per year if the peak toll was set at $13.20. That's not the most the agency could raise with congestion pricing, but also not the least. Such a scenario would cause a 17-percent drop in the number of vehicles entering the congestion zone of Manhattan and an 8.4-percent drop in vehicle miles traveled in the area as well. Without congestion pricing, 716,150 vehicles would enter the CBD every day, according to the environmental assessment. No matter which toll is chosen, the number of cars drops by between 110,237 to 142,855 per day (see page 8, Table 4A2.2)

Better still, the agency said, Scenario B2 wouldn't include additional negative impacts from the congestion pricing, such as tolls being applied to buses (including, ironically, MTA buses) or tolls on trucks that are so high that truck drivers seek alternative route.

"This further demonstrates that the mitigation commitments in the final EA would not result in effects beyond those already described," the agency said.

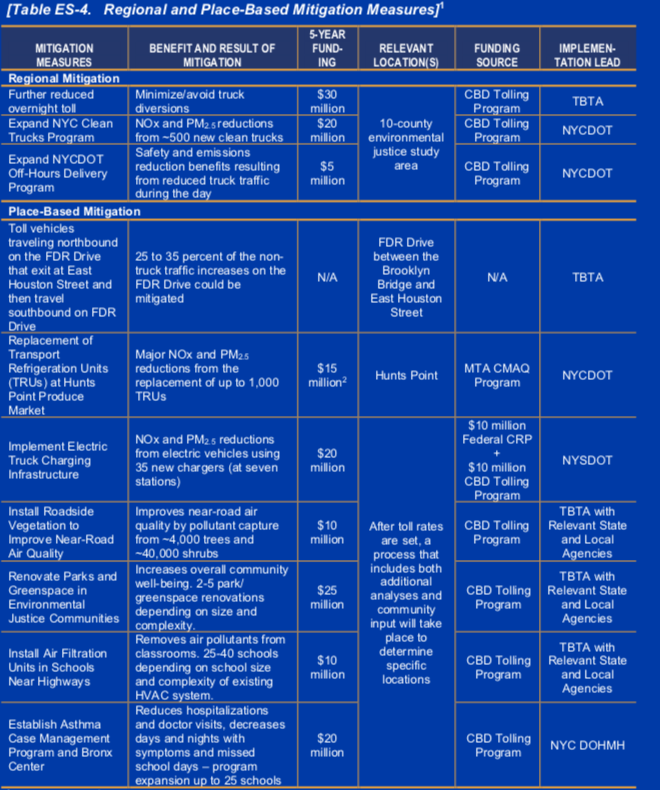

The new discount and tax policy are in the EA in addition the previously reported mitigation efforts the MTA said it would undertake to offset already identified possible negative effects of the traffic toll under all of the tolling scenarios, such as a slight increase in truck traffic and air pollution in environmental justice communities near highways. Because of those impacts, the agency offered to pay $130 million over five years for mitigation efforts such as converting diesel-powered refrigeration trucks at the Hunts Point Market to electric. That cost has risen to $155 million over five years, though most of the increase is thanks to $10 million from the federal government to install electric truck charging infrastructure.

Even with these measures in place, the six-person Traffic Mobility Review Board still makes decisions on the rest of the policies for the traffic cordon, such as the actual price of the toll and who, if any, gets exemptions from the toll or credits for crossing bridges and tunnels and that have tolls on them. That last part will be key, one expert says, to ensure people aren't trying to drive through other neighborhoods to avoid paying a toll.

"The bigger policy issue is going to be credits, and how to implement a program that equalizes costs to similar destinations to the extent possible," said Regional Plan Association Executive Vice President Kate Slevin. "This will be key to reducing 'toll shopping' and reducing traffic in local neighborhoods near bridges and tunnels."