BAM — the storied Brooklyn arts institution known in part for its whimsical bike racks designed by cyclist and musician David Byrne — is throwing every possible excuse at local leaders in an attempt to stop a city plan to put a protected bike lane outside its Fort Greene campus, Streetsblog has learned.

Brooklyn Academy of Music President Gina Duncan cited vague "safety concerns" in an April 11 letter arguing to leave cyclists unprotected on Ashland Place — a critical street for bike commuters that feeds directly into the Atlantic Terminal transit hub.

“Due to serious safety concerns, BAM would like to strongly urge you to not support the plan for protected bike lanes along Ashland Place," Duncan told Brooklyn Community Board 2 Transportation Chair Sidney Meyer in the letter, which was obtained by Streetsblog.

The 162-year-old performance venue "works on this block all day every day and we do not feel it is a safe route for cyclists," continued Duncan, who referred to the safety of people who bike on the strip as a question of "operating costs."

“Our operating costs will increase as the responsibility for safe streets is shifted onto us,” she said, without offering evidence.

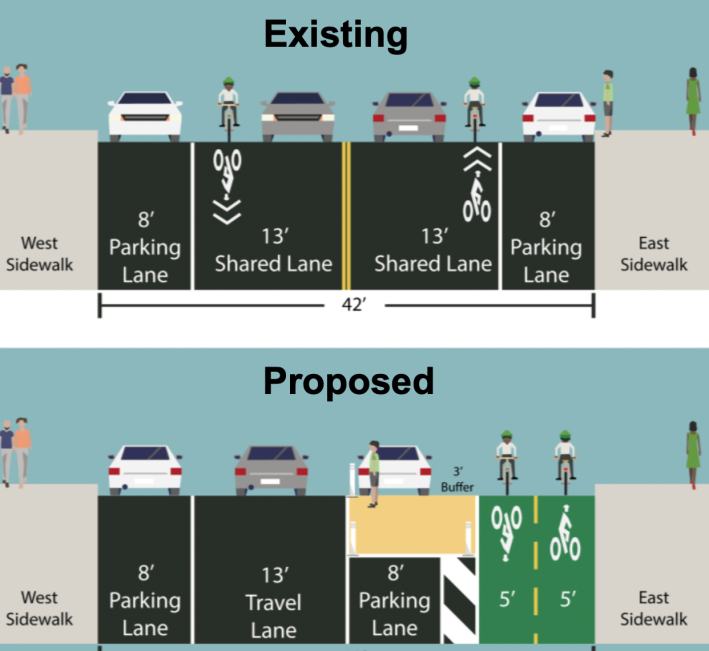

DOT unveiled plans for the Ashland Place redesign last summer — a year after it added protected bike lanes on Navy Street, which connects cyclists coming from the waterfront to the area around Atlantic Terminal. The project has yet to be installed, however, and is up for another hearing at the CB 2 Transportation Committee meeting this Thursday.

The proposal would convert parts of Ashland Place from two-way to one-way northbound to make room for a two-way bike lane protected by concrete barriers and vertical delineators along the east curb — including outside BAM's campus at Lafayette Avenue and Ashland Place, according to renderings from last summer [PDF].

BAM uses the block of Ashland Place between Hanson Place and Lafayette Avenue to load and unload equipment and stage materials, Duncan said in her letter.

“Converting Ashland to a one-way street will cause problems for the operations of businesses on both sides of the street,” she wrote. “If Ashland Place becomes a one-way street, we have significant concerns about large trucks maneuvering down the street and being routed through residential streets.”

The arts exec did not explain why the existence of curbside delivery precludes the presence of protected bike lanes, several of which already sit adjacent to theaters in other parts of the city. The Beacon Theater on Broadway between 74th and 75th streets on the Upper West Side, for example, has a loading zone on Amsterdam Avenue, where there’s also a protected bike lane.

Ashland Place is already a popular and at times dangerous route for cyclists due to its central location and proximity to Brooklyn's busiest transit station. There have been 104 crashes on the 3,000-foot stretch between Myrtle Avenue and Hanson Place since January 2020, causing 53 injuries, including to 16 cyclists and five pedestrians, according to city stats compiled by Crash Mapper. A UPS driver killed 27-year-old Sumiah Ali at the corner of Ashland and DeKalb Avenue in February 2017.

“BAM needs to look at what city they're in because Ashland is already a major bike route, it directly connects to the Manhattan Bridge. That’s why it needs to become a protected bike lane,” said Bike New York spokesman Jon Orcutt, who urged the city to ignore BAM’s objections.

“It’s unreasonable and wrong and DOT and elected officials should move on with the project.”

Duncan’s theory that a one-way conversion would make it harder for her staff to do their jobs is bunk, said Orcutt, a former city DOT official under mayors Mike Bloomberg and Bill de Blasio.

“Frankly, trucks will have an easier time maneuvering on a one-way street that has more room for trucks than a skinny two-way, which is a lot more complicated in terms of intersections and just driving,” Orcutt said.

In her letter, Duncan also invoked the Two Trees-owned residential development across the street from BAM at 300 Ashland Place, saying its presence further complicates the bike lane proposal.

“Between loading for the businesses and tenants in 300 Ashland, and our own unloading and loading, this block is not an appropriate location for safe bike infrastructure and increased bike traffic,” she said.

A rep for Two Trees said that the real-estate firm “supports the bike lane” and is “working with other stakeholders in the community to ensure it is implemented in the best way possible.” Two Trees declined to comment further.

The Brooklyn Hospital Center, which also operates loading zones and entrances on Ashland Place, declined to comment.

DOT still plans to present the plan to the community board on Thursday, according to spokesperson Vin Barone, who said the redesign "would significantly enhance safety along a critical cycling corridor."

Community Board 2 leadership declined to comment. Attempts to reach David Byrne were unsuccessful.

A rep for BAM said the organization hopes DOT considers "alternative plans."

"BAM is very supportive of safe biking infrastructure and we agree that protected bike lanes are essential for our borough," said the spokeswoman, Sarah Garvey. "We look forward to a continued dialogue and to discussing alternative plans that better prioritize cyclist safety."

At least one local found BAM's outspoken opposition "disappointing."

"To address BAM’s concerns, we support the addition of loading zones to accommodate their needs as part of this project," Andrew Matsuoka, Fort Greene resident and a volunteer leader for Transportation Alternatives.

"We expect NYC DOT to install protected bike lanes on Ashland Place and Navy Street, closing the gap in otherwise continuous protected routes from Sunset Park to Manhattan," Matsuoka said. "I am very excited that I will be able to ride safely here in the very near future.”