New York City policies and laws promise us safer streets, but drivers kill hundreds of people every year, including themselves. And what doesn’t kill us makes us less strong, with asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and many missing limbs and lives destroyed.

Add to that the fact that most New York City households don’t own a car. Yet our government still gives most of the space on our city streets to the movement and storage of motor vehicles. And that interferes with the city life most of us want.

Let's look at some of the implications of that.

Civil streets

State Attorney General Letitia James unwittingly suggested one way to get the streets New Yorkers want and need. As reported in Streetsblog, James wrote that a newly built truck depot in Harlem may be a “public nuisance” because it “interfere(s)” with or “cause(s) damage” to a “public place or danger(s) or injure(s) the property, health, safety, or comfort of a considerable number of persons,” as state law puts it.

“Trucks are associated with increased traffic delays, noise, and vibrations, and can endanger the safety of pedestrians and cyclists. Trucks also generate local air pollution,” James declared.

If we use the same criteria, for New York City streets, most meet the state's "public nuisance" definition. Many city streets in Europe were once as dangerous and polluted as New York’s, but all over that continent, cities are making better streets while cutting traffic fatalities to a fraction of ours. We should, too.

Traffic deaths

Because our streets are so dangerous, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio introduced “Vision Zero” in 2014 in hopes of slowing down traffic with new road designs. The stated goal was to reduce traffic deaths to zero by 2024 (the DOT later moved the goalpost to 2030).

Yet as Justin Davidson wrote in his recent story in New York magazine, we're moving in the wrong direction.

“The Department of Transportation boasts of having ‘driven’ — its word — ‘traffic deaths to historic lows,’” Davidson wrote, “which is true if by ‘history’ you mean since last year.”

In fact, the previous year was the worst for pedestrian deaths in New York since Vision Zero began. In each of the last nine years, an average of 125 pedestrians were killed in collisions on the streets of New York City, or one every three days.

Altogether, 255 people died in New York traffic last year. Since Vision Zero started, the annual total has never gone below 200. Nationwide, we accept more than 40,000 deaths every year, despite all the elaborate and expensive safety devices in our cars (to protect the passengers). The deaths are seen as part of the cost of keeping traffic moving at a “reasonable” speed.

Our streets would be safer if we more closely followed the practices of cities like Helsinki, Oslo and even Hoboken. All of them reduced pedestrian and cycling deaths to zero. But New York continues to emphasize moving cars into, out of, and through the city.

Pollution

Americans, who drive everywhere, have been the world's biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. But even in New York — where most of us don’t own a car and we have the best transit in North America — cars and trucks are still responsible for nearly 30 percent of the air pollution,

In Manhattan, only one-quarter of households own a car. Statistics from the DOT show that the streets around city highway exits, bridges, and tunnels where drivers enter Manhattan are particularly dangerous — as in my neighborhood on the Upper West Side. Neighborhoods next to highways also have the worst air quality. But when we get an opportunity to fix that, we spend billions of dollars to keep people driving in and out.

One big opportunity is before us: The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway is falling down — yet the only plan being consider is a multi-billion-dollar rebuilding. No one, it seems, is willing to turn off the fire hydrant that is pumping cars and trucks through the city. We will rebuild a highway that divides Brooklyn neighborhoods, kills New Yorkers with pollution, and delivers to Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan drivers who also kill New Yorkers.

How about a better plan? When an earthquake damaged the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco, that city tore down the rest of the highway. The resulting Embarcadero Wharf is now one of the most popular places in the Bay Area.

Yes, congestion pricing is coming — but it only shows that we choose to take one step forward and one step back instead of seizing the opportunity to create solutions that will reinforce the congestion zone, reduce traffic citywide, and bring innovative 21st-century fixes to 20th-century problems.

When it comes to climate change, we’re staring into the abyss but driving like it’s 1999. We are driving ourselves into a catastrophe.

City streets

"The right to access every building in a city by private motorcar in an age when everyone possesses such a vehicle is actually the right to destroy the city." —Lewis Mumford, New Yorker and New Yorker writer

New York's streets are extensions of our apartments. In a city like ours, a lot of public life takes place in public space, and most of our public space is in our streets, yet we give 70 percent of that space to the movement and storage of machines.

It wasn’t always like this, of course. Most of our streets were laid out long before cars existed. Think of life in Lower Manhattan before the car: streets full of carts that immigrants used to gain a foothold in the new world. Their children invented games they played in the streets, like stickball, stoopball, ringolevio, kick the can, double dutch, and many more. As recently as the 1950s, parking overnight on New York City streets was illegal.

We see what we've lost, and we want better streets for a better life. Cars take away public space and assault us with noise and pollution. In a double whammy, New York has become the place of wailing, ear-damaging sirens — the sound of emergency workers unable to do their job because they're stuck in traffic.

This transformation of the city happened because it created a new national transportation system based on cars. Before the arrival of the motor car, we had a great national network of trains, streetcars, and subways. We replaced that with a system using private cars on public streets. Now a significant percentage of the country thinks they have the right to drive wherever they want, regardless of the consequences for others. Very few people need to drive into Manhattan, but New Yorkers are kicked to the side of the road so others can drive around our great city.

What is to be done?

I’ve written tens of thousands of words about how to make safer streets that are better for public life. You can see the ideas in the book I wrote with Victor Dover, Street Design, The Secret to Great Cities and Lives. There’s more at my website, Slow New York.

I can’t read the minds of our elected leaders about why they don't change the status quo in New York. We know they have donors and influencers who support the current system, including rich New Yorkers who move around the city in chauffeur-driven cars or the companies who profit from highways.

The Department of Traffic (what I call it) has to take a lot of the responsibility for the state of our streets. The state and city DOTs control enormous federally funded budgets for maintaining the streets. That gives them great power. Think of Robert Moses.

Fifteen years ago, New York City had the most progressive DOT in America. But other cities took greater advantage of the opportunity presented by Covid. San Francisco, for example, created a permanent, citywide network of open streets they call “Slow Streets.” Three years after Covid started, New York has a small number of scattered, disconnected Open Streets that are popular, but shrinking in number (mostly because the program relies on volunteers and outside funding).

Last month, a citizen activist group won a lawsuit against the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Another citizen group is using the same legal argument — also known as an Article 78 suit — to stop the expensive public-private development of 10 supertall office buildings around a renovated Penn Station.

Jeff Speck, a colleague at the Congress for New Urbanism, has started working on similar ideas at the national level. That’s interesting, because he works with mayors and DOTs around the country that want to make their cities more walkable.

"Put simply,” Speck wrote in The Hill, “the roadway design standards enshrined by our nation’s professional civil engineers are unnecessarily deadly to the point of criminal negligence. It’s time to place blame and demand change."

Good news

There are two pieces of very good news. The first is that the Biden administration has set aside money for improving neighborhood streets and removing city highways. America built the national network of highways and modern, auto-centric arterials with federal funding. New York has the opportunity to use federal money to dismantle some of it.

Second, Mayor Adams has appointed a director of the public realm who will coordinate city agencies that work in public space, including the departments of Transportation, Parks, Climate, Buildings and Environmental Protection.

The name of the first director is Ya-Ting Liu. I wish her and her successors all the luck in the world. I hope their power quickly expands. Traffic engineers do not lead the design team that make the beautiful, safe, low-traffic streets for people we see in Europe. Those streets are 21st-century paradigms for moving away from the car-dominated models of the 20th century that still plague us.

New York has been a model for the nation, and can be again. No place in America is more ready for safe, slow, walkable streets.

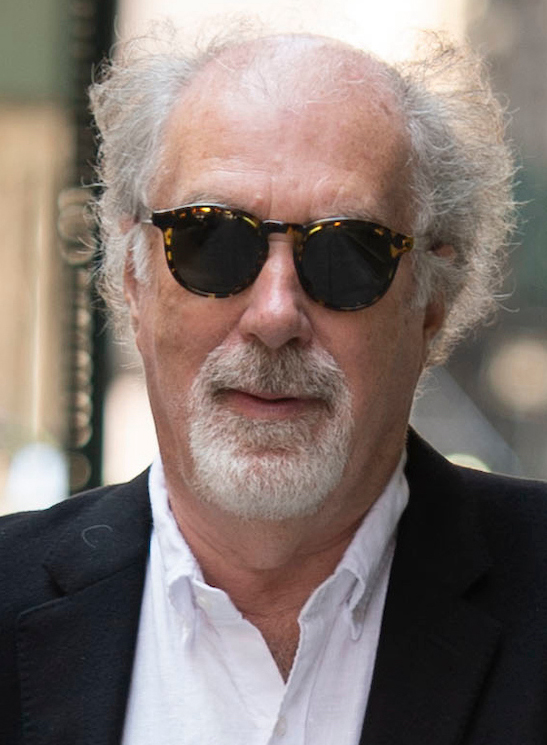

John Massengale is an architect and urban designer. Follow him on Twitter @jmassengale. To register for the workshop, click here.