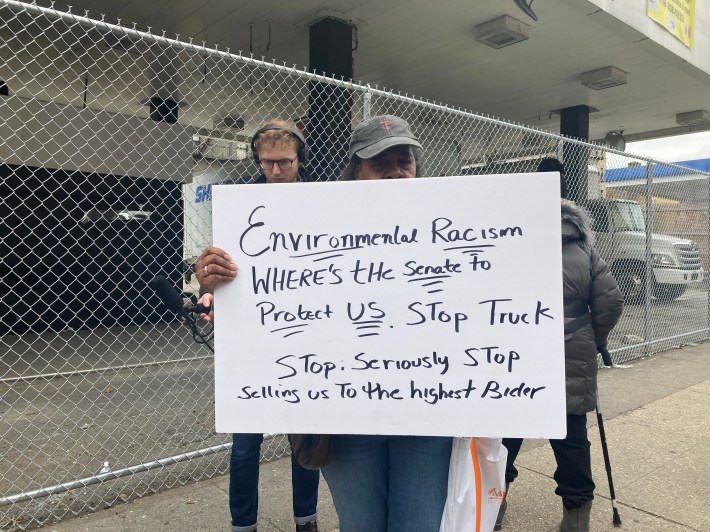

Manhattan Council Member Kristin Richardson Jordan rallied on Saturday with a few dozen community members at the newly opened truck depot in Harlem, decrying the developer’s brazenness in bringing more pollution-spewing trucks to a low-income community of color that’s already been forced to bear other environmental injustices.

The freshman pol promised to fight the depot — where developer Bruce Teitelbaum had hoped to get a rezoning to build a pair of 32-story buildings comprising more than 900 units of housing and a Museum of Civil Rights until Richardson Jordan opposed the development. She says she still has no plans to meet with real-estate bigwig even as the trucks roll.

“My theory of change is based in people power so I believe that if we organize, if we lobby the state legislature around this truck depot and we shut this down, and then we put pressure on this developer that they will come back and build something that this community actually needs,” Richardson Jordan said. “I don't believe in private back-door deals with developers, I don’t see it as something where I need to individually coax him, I see it as not personal but community. We have seen our community displaced, rejected, a dumping ground for environmental waste like this truck stop."

Teitelbaum claims he was “forced” to withdraw his application in April to rezone the site at W. 145th Street and Lenox Avenue after Richardson Jordan doubled down on her opposition to his proposal, called One45. According to the city’s 1961 citywide zoning code, only “automative and other heavy commercial services” as well as market-rate housing is permitted on the site.

And on Wednesday, Teitelbaum opened parking for commercial trucks, instead of housing for people. A sign bearing the words, “Park Your Fleet,” now looms above 145th Street. In addition to the truck depot, Teitelbaum says he’s now also looking into building a self-storage facility as well as market-rate and luxury housing.

As part of the rezoning, Teitelbaum — once an aide to former Mayor Rudy Giuliani — says he also would have reconstructed the playground within Brigadier General Charles Young Playground and redesigned the street. Though exactly what his plans were for a street redesign remain unclear, and he declined to comment further.

But bringing more gas-guzzling trucks to an area that already disproportionately suffers from environmental injustice harms high rates of child hospitalizations associated with pollution-induced asthma. According to city health data, that section of Harlem adjacent to the 145th Street bridge to the Bronx had an annual rate of 39.2 per 100,000 children, more than double the citywide average.

“[The developer] should be embarrassed, but they're not,” said Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, who was also on hand on Saturday. "We should look at the needs and what communities like Harlem are dealing with, intersections of lack of housing and environmental issues like asthma that are connected of course to trucking. So why would you bring to Harlem a truck depot? What you're saying is you never really cared about this community."

In Harlem today where Council Member Kristin Richardson Jordan and @JumaaneWilliams are rallying with community members against the new truck depot pic.twitter.com/91Scso7pmZ

— Julianne Cuba (@Julcuba) January 21, 2023

At the heart of Richardson Jordan’s opposition to Teitelbaum's original proposal is the income-level brackets of the units in the buildings. Richardson Jordan says she still, and has always, demanded a minimum of 30 percent of the units set at 30 percent of the area’s median income, and 60 percent to be set at 60 percent AMI and below.

“That's the bare minimum. This developer didn't want to meet those standards,” she said.

But Teitelbaum had proposed many levels of below-market-rate housing: Out of 915 units, 112 units would be pegged at 30 percent AMI and 255 units at 50 percent AMI. Another 91 units were scaled to 125 percent AMI. The rest would be reserved as market rate and luxury units, Patch reported last May, according to information from Richardson Jordan’s office.

Richardson Jordan also alluded to some kind of illegality of the truck depot operating on the site since it sits within the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s Brownfield Cleanup Program, which encourages the cleanup and redevelopment of contaminated sites.

“The truck stop is a nonstarter that our state officials should be acting upon as there should be no state business license permitted of an environmentally hazardous business in an environmentally protected area,” Richardson Jordan said in an e-mailed statement to Streetsblog last week.

But a DEC spokesperson said a truck depot is a permitted use of the site.

And now that the truck depot is up and running and luxury housing is a possibility, Richardson Jordan still refuses to meet one-on-one with the developer to reach a new deal that works for her and the community.

“I was very happy to have a meeting that involved members of the community,” she added on Friday. “I have never turned down having a meeting as long as we are involving community members as well.”

In a statement to Streetsblog after the rally on Saturday, Teitelbaum called Richardson Jordan a "grandstand[er]" and blamed the council member as the reason there are trucks, not apartments on that site.

"We acknowledge that siting a truck depot where affordable housing should be is not the best result, but that’s CM Richardson’s fault, not ours. She knew that her decision to sabotage One45 would mean trucks, not homes, for Harlem," he said. "We are not unmindful of our neighbors who we respect and whose concerns and needs we pledge to address in good faith as we move forward with our plans. Instead of always protesting and yelling, maybe Richardson should do her job and start talking to us, which she refuses to do."