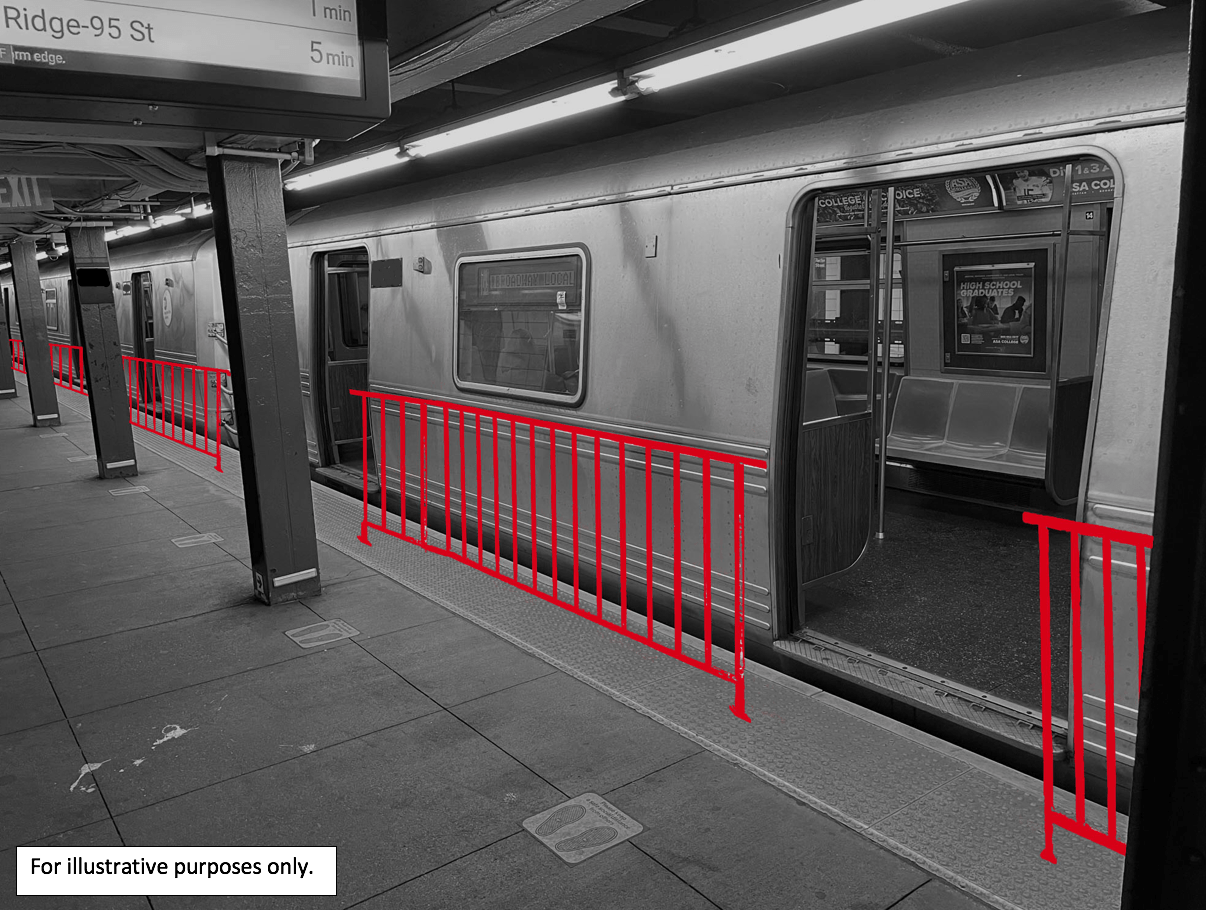

Over the last few weeks, proposals have been floated to improve subway-rider safety by installing walls and operable doors on platforms — a costly measure that would take many years, according to the MTA. But there’s another way to substantially improve safety, for a fraction of the cost of those measures: installing standard, fixed railings at the platform edge in the area between the subway car doors.

Late last week, the MTA released a 3,000-page study from 2020 of potential “platform barrier systems.” The study concluded that such systems were only feasible on about one-third of stations and, even then, the cost would be $7 billion, with another $119 million in annual upkeep. MTA Chairman Janno Lieber stated that MTA would review options again because the agency believes that “there is an urgent problem and we need action today” because of the rising incidence of subway pushings and the tragic murder of Michelle Alyssa Go at the Times Square subway station on Jan. 15.

Lieber is correct that this is an urgent problem; the MTA could take action today — and not in the indefinite future — by adopting the truly feasible, relatively simple solution of standard, fixed railings.

I’ve worked in real-estate development and construction for 20 years, including seven in the public sector. I spoke with contractors I’ve worked with who gave me a cost to furnish and install stainless-steel railings of $350 to $400 per foot. (That cost may strike some as high, but this work is on the platform edge, steel prices have risen recently, and the installation is calculated at "prevailing-wage" rates, which is the cost of union labor on public projects.)

SIDEBAR: HERE ARE THE QUESTIONS WE SHOULD BE ASKING ABOUT PLATFORM GATES

At that rate, I took four busy stations in Manhattan and the two busiest in each of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx and came up with a total cost of only $13 million to add protection to all 10 stations. Across just the 10 stations, the treatment would protect about 200 million riders annually. (The precise stations to be upgraded should be the subject of discussion among the MTA, elected officials, and community leaders. I chose the 10 stations — Times Square, Grand Central, Union Square, Penn Station, Third Avenue-149th Street, 161st Street-Yankee Stadium, Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center, Jay Street-Metrotech, 74th-Broadway/Jackson Heights-Roosevelt Avenue, Flushing-Main Street — for illustrative purposes.)

For context, in 2017 the MTA spent $24 million on largely aesthetic upgrades to the Prospect Avenue R train station. Only 1.6 million rides originated at that station in 2018.

Obviously there are limitations on this approach. There would be gaps at car doors. But, using Grand Central as an example, you could quickly protect 85 percent of the platform edge — a huge safety improvement!

Also, the concept works best on lines on which the local and express trains have similar car configurations. That includes all the IRT numbered lines, but many stations on the BMT/IND lettered lines also could be protected. To underscore the feasibility of this approach, consider that the door locations have been marked in tile at the Grand Center subway station because the 4/5/6 trains have such similar configurations. Again, the concept is simple: Put fixed railings where there aren’t doors.

Another benefit to this approach is that fixed railings are a flexible system that can be customized in order to ensure accessibility, depending on station layouts.

The MTA’s 2020 report did note the possibility of using fixed railings for subway-platform protection, but fixed railings were “eliminated early in the study due to expressed concerns … regarding the potential injury they could cause to customers due to door dragging incidents,” per the study. Door-dragging incidents are a serious matter. Unfortunately, the number and nature of door-dragging incidents aren’t tracked in any published MTA safety reports and so the trade-offs of those versus train-strike incidents can’t be analyzed. The platform wall and operable door solutions that the MTA studied, however, would appear to cause the same potential for complications in door-dragging incidents. Fixed railings also could be set back from the platform edge in order to minimize such complications.

The bottom line is that installing standard, fixed railings between car doors is a quick, cost-effective, low-tech way for the MTA to improve the safety of riders substantially. It is a good, but not perfect, solution that deserves more consideration than one sentence in a 3,000 page report. The gravity of the consequences of further inaction demands prompt reconsideration.

Charles Gans (@charles_gans) is the senior vice president of development at Trinity Place Holdings. He was formerly the executive vice president for real-estate transactions at the New York City Economic Development Corporation and a construction manager at Lend Lease. The views here are his own.