Amid the bloodiest year in Mayor de Blasio’s Vision Zero, Streetsblog continues its seven-part series focusing on a key strand in the movement for livable safe streets, written by a central figure in that movement, Charles Komanoff. A former head of Transportation Alternatives, Komanoff 25 years ago launched a highly effective public awareness campaign calling out the daily carnage on New York City streets. Under the name “Right Of Way,” his group brought the brutal reality of pedestrian and cyclist deaths to the public eye in the form of high-visibility street actions (including one arrest). Part I opened with the first "Killed by Automobile" stenciling in December 1996. Part II focused on how the movement began to generate press coverage. Part III looked at how the movement branched out. Part IV looked at the publication of the book, "Killed by Automobile." And Part V offered a sobering look at what happens when the car culture pushes back.

Right Of Way, mostly dormant in the aughts, regrouped in 2013. The revival was short-lived, spanning just two years, but spectacular.

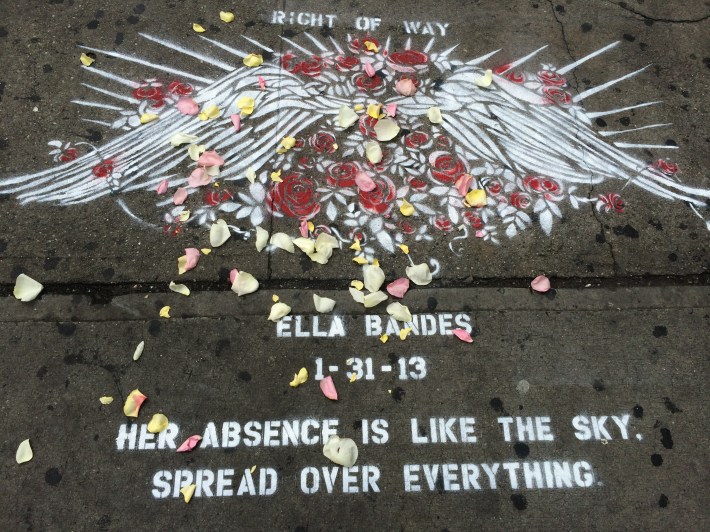

The return to action brought together several original Right Of Way members with a cast from the direct-action, grassroots Time’s Up! If this new phase had a defining feature, it was replacement of the splayed, graphic “flatso” with a stencil suggesting sunlight flickering through wings and roses.

A few of of the old guard chafed at this, as well as at our retirement of the harsh, factual KILLED BY AUTOMOBILE epithet. Yet the new imagery opened the action to a more formidable constituency: the families of those killed by drivers.

Prior to each stenciling ride, family members were invited to contribute a phrase to be inscribed alongside their loved one’s name and date of death. These became haikus of grief and remembrance: MISSED BEYOND MEASURE • OUR SMILING ANGEL • FOREVER LOVED, FOREVER MISSED, NEVER FORGOTTEN • THE SONG CARRIES HER AS SHE WAS.

The new, sheltering image and the participation of the families helped us flip the script from the prior, stealthy stenciling. The streets, violent graveyards, were being consecrated, and not even Police Commissioner Bill Bratton’s cops would dare bust up these shrines. Knowing this, we and the families could take time to reflect, cry and hug, graced, it seemed, by the hovering presence of their loved ones.

On each stenciling expedition — one summer day, our cyclist caravan started in the Bronx and snaked 84 miles through the Upper East and West Sides, Midtown, Long Island City, Flushing, Elmhurst, Woodside, Bushwick, Prospect Park, and out to Far Rockaway and back — families would drive or, on occasion, cycle with us, from site to site. A parent or spouse might wield a spray can or help position the stencil boards, not just for their own loved one but for another’s.

Along with our original aim of placing evidence of driver violence in plain sight, our stenciling now gave devastated families a means to bond and organize. It’s probably not coincidental that the support and advocacy group Families for Safe Streets took root around the time, in 2014, that we switched to a more companionable form of memorial making.

Right Of Way’s stenciling resurgence took place in the context of newly elected Mayor de Blasio’s stated commitment to “Vision Zero” — a goal to eliminate traffic deaths by 2024. But as de Blasio racked up legislative successes — lowering most streets’ posted speed limits by 5 mph to 25, and expanding automated enforcement of speed limits and red lights — policing pressed on as before, oblivious and cruel.

This dissonance erupted before our eyes on a Sunday in January, 2014, the new mayor’s first month in office. We had just painted a memorial at Amsterdam Avenue and 96th Street — #6 of “7 over (age) 70” stencils that day in Queens, Bronx and Manhattan — when we encountered a gang of cops bloodying 84-year-old Wong Kang for allegedly disobeying their order to refrain from crossing Broadway mid-block — one of 18 pedestrians ticketed that weekend by the 24th Precinct. On the ground, little was actually changing.

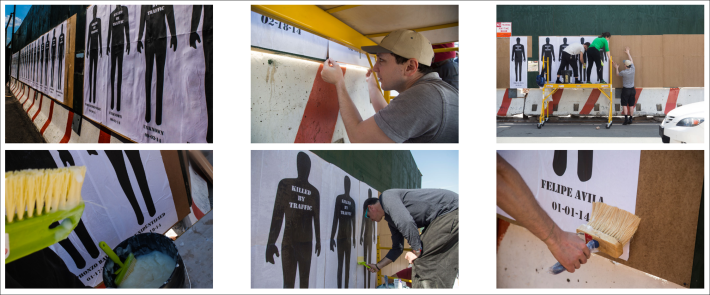

Right of Way’s last major action, in April 2015, was an extravaganza: a 450-foot mural memorializing every victim of a New York City traffic crash in the previous year. The installation, comprising 264 five-foot-high, 20-inch-wide panels, covered two-and-a-half sides of a full-city-block construction fence north of the Williamsburg Bridge near the Brooklyn waterfront. Each person was represented by a black silhouette with their name and the date they were struck and killed, mounted on white panels, arranged in chronological order.

The memorial wall, caustically code-named Vision 264, was, unlike our original project, street-legal, okayed by the site’s private owner. It was short-lived, washed away the next day in a drenching downpour. Yet it radiated power in its making. As one of the organizers noted in a video of the installation, “People walking by have been asking us if this is everyone who died in [traffic crashes in] the United States last year, and they’re shocked to find out that this many people were killed in New York City alone.” Among the scores of volunteers who wheat-pasted, materiel-hauled or power-drilled that day were parents whose son’s or daughter’s image appeared on the wall.

Save for a few more memorial rides, Vision 264 was Right Of Way’s last action. Other demands for justice were coming to the fore, most notably the calls to end racialized violent policing that swept over the city and nation after the killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice in 2014. And as we saw in our earlier, 1996-2000 incarnation, sustaining any egalitarian and voluntary initiative is difficult in any circumstances.

Fortunately, Families for Safe Streets was able to institutionalize under the aegis of its sponsoring group, Transportation Alternatives. Since 2014, FSS has driven the policy and political agenda for safer streets through conferences, campaigns, demonstrations and annual commemorative events like last month’s Day of Remembrance at Brooklyn’s Borough Hall. Their power was on vivid display in early 2019 when the group brought scores of survivors of killer-driving to Albany to demand, and win, legislative passage of congestion pricing — tolls on drivers and thriving transit being elements of the toolbox to shrink and end traffic violence.

What is Right Of Way’s legacy? Did it, like the stenciled memorials themselves, glow for awhile, only to vanish? I think not. I believe it lives in many places. We rubbed the public nose in drivers’ routine, unreckoned-with aggression and mayhem. We helped put an end to pedestrian and cyclist victim-blaming; our research irrefutably outed it as a lie. We planted a thought in the minds of untold thousands of New Yorkers who saw our memorials and wondered: what happened, who did that, what are they saying here?

We stood alongside the families of the slain. This is not a small thing.

If Right Of Way deserves a measure of credit for helping Families for Safe Streets achieve organizational critical mass, it may also be that in the larger culture we helped seed new currents of feeling that now are demanding without apology to reclaim cities from automobiles.

And for ourselves, we experienced the power of direct action done outside of organizational structures, on little more than pure conviction and good old New York in-your-face chutzpah.

I give the last word to one of my Right Of Way partners with whom I shared drafts of these pieces: “I was very fortunate to have had that experience — dodging around through the dark streets, in parts of New York I would never otherwise have gone, worried about the cops and yet utterly convinced, beyond the least shadow of a doubt, that we were doing the right thing — the Lord's work. My granny would have said. It was a defining moment in my life, when theory hit the road. I'm very grateful for it.”

Look for the series postscript on Monday.