Eric Adams may bike to his inauguration when he is sworn in on Jan. 1 — which would be a fitting symbol for our times, when the bicycle has become an essential element of the urban landscape and character of urban life. After all, Adams has pledged to pedal his way to City Hall regularly — and to add some 300 miles of protected bike lanes, a couple of “bicycle superhighways,” and a long-sought bicycle pathway across the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.

Adams ought to cement his commitment to cycling by choosing a transportation commissioner who embraces it, and by enacting policies that make it clear to the many opponents of cycling that the current cycling boom is here to stay. Summer Streets, when the city turns over a few of its roads to cyclists, pedestrians and skaters for a couple of days in August, should be Everyday Streets. Private automobiles should be banned from large parts of the city and all motor-vehicle traffic from certain districts. New bridges should be built for the exclusive use of bikers and walkers. And the ordinary streetscape of neighborhood after neighborhood should prioritize people on bikes and feet.

Out goes on-street car parking. In comes generous sidewalks; wide, protected, and seamlessly integrated bicycle lanes; and even street lights that are timed to their pace.

To realize this glorious vision, Adams need only learn the lessons of the past: The city’s cycling history has consisted of many booms like the one we are experiencing today, but they have all been followed by relatively long busts.

New Yorkers embraced the first bicycle-ish devices, which arrived in 1819. Yet lawmakers soon banned them from the very places they were most likely to be used — City Hall Park, Bowling Green, the Battery, and the sidewalks. A half-century later, in 1869, the city experienced the so-called velocipede craze, which also lasted just months. For all the obvious reasons, the teetering high-wheelers never attracted a mass following.

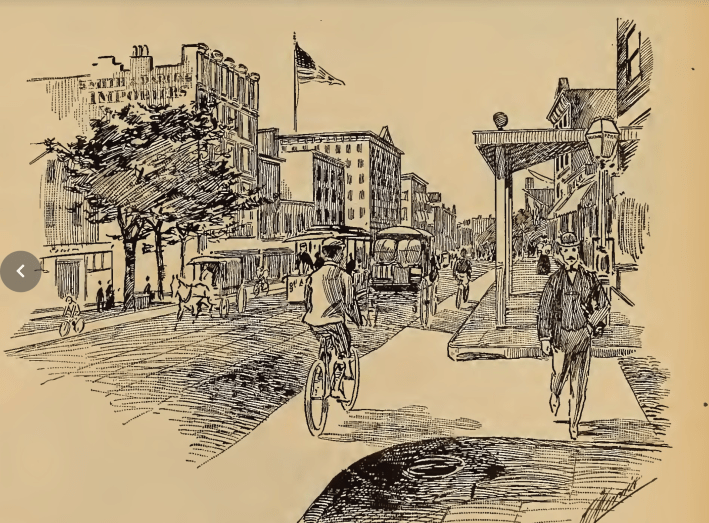

Then, in the 1890s, the modern bicycle made its debut, and with it a much more substantial boom. On a per-capita basis, more New Yorkers rode bicycles than ever before or after. Lower Manhattan, with dozens of bike shops, became known as "Bicycle Row." Cyclists, almost all of whom were brand new to the activity, demanded that the city adapt — and, so, it did.

In Brooklyn, parks commissioners built the greatest bicycle path in America, stretching from Prospect Park to Coney Island. Museums and restaurants began employing bike valets. Bicycle clubs (the primary lobbyists) oversaw the construction of on-street bike lanes. State and city lawmakers codified the bicycle as a legitimate vehicle, granting it a right to the road that still stands. It seemed that New York was destined to become a city designed for and around the bicycle.

The 1890s boom, while longer than the earlier ones, still lasted less than a decade as the fashionable set chucked their wheels. Another wave came in the 1930s, and then another in the late ’60s and early ’70s. When Ed Koch became mayor in 1978 he briefly fell in love with bikes, even learning to ride a bike for a photo op celebrating the opening of a Sixth Avenue bike lane in October 1980. By Thanksgiving, he ordered that the lane be ripped up.

Amid each boom, some advocates would say optimistically, “this time is different.” It never was, and each time they had to start over. The infrastructure built during one moment of enthusiasm usually had disappeared by the time the next one came.

So you’d forgive me for being skeptical about the latest bicycling boom. It hardly seemed destined to endure, having started in the era of Mayor Bloomberg, who had no genuine interest in cycling. In 2007, however, he tapped Janette Sadik-Khan to serve as transportation commissioner. She proved transformational, launching the two programs that radically changed the way New Yorkers came to understand the bicycle’s place in the city: protected bike lanes and Citi Bike.

Many New Yorkers thought Sadik-Khan was nuts — and not just the right wing. John Liu, then the comptroller, alleged that Citi Bike was pushed through in a misguided “rush to place ten thousand bicycles on our streets” at the expense of “young children and seniors.” Iris Weinshall, a former DOT commissioner and wife of Sen. Schumer, fumed (and sued) over the bike lane along Prospect Park West. Brooklyn Beep Marty Markowitz and then-Rep. Anthony Weiner complained, too. Scott Stringer — at the time, the Manhattan borough president — questioned whether Sadik-Khan could build “long-lasting” projects with genuine community support and not a “my way or the highway” attitude. Then-Council Member Letitia James alleged that Sadik-Khan was “pretty much despised by my colleagues.”

Yet Sadik-Khan's innovations became the model. Although Mayor de Blasio (another Sadik-Khan critic) called himself a progressive, he became known for logging countless miles in his black SUV, driving (among other places) to his preferred Brooklyn gym. He continued Bloomberg's legacy but without the elan that Sadik-Khan brought to the task, building more Citi Bike stations, adding more protected bike lanes, and improving access over the bridges. In the primary campaign earlier this year, the Democrats all said essentially the same thing.

Sadik-Khan’s approach may have been “alienating,” as de Blasio charged, but the fact that she was willing to break convention and unwilling to sit tight led to the transformation that many former critics now take for granted. The protected bike lanes that she piloted and Citi Bike, the most significant development in New York City bicycling history, radically altered the streetscape calculus and invited many more residents to consider bicycle commuting.

Of course, most people still don’t ride. Bike infrastructure disproportionately remains located in wealthier, whiter communities. As traffic fatalities rise, blame for chaos on the streets still falls on the shoulders of cyclists. In a piece this month on the cycling boom, a New York Times columnist felt compelled to add that “in some neighborhoods, residents complain that cyclists have become a menace.” An Upper East Side woman described the constant “danger” of the reckless riders, who, by the way, call her “grandma.”

Although cyclists are not innocuous, the threat they pose always has been exaggerated. In the 19th century, cycling opponents called them “scorchers,” an epithet evoking the image of a reckless young man hunched over his wheels, barreling down the sidewalks and frightening horses and toddlers.

Even with “scorcher” rhetoric, Adams inherits the city's longest bike boom and a political landscape that largely has embraced the bicycle, affording him more opportunities than any other incoming mayor. He can, as he promises, expand the bike-lane network and the Citi Bike footprint. Or he can aim for transformation. In which case, he should hire Janette Sadik-Khan — or someone just like her.

Professor Evan Friss (@EvanFriss) is the author of "On Bicycles" and "The Cycling City" and curated the Museum of the City of New York's 2019 "Cycling in the City" exhibit.