The city must eliminate free parking, dramatically reduce roadway space for cars, and transform the Department of Transportation into a broader "public space management" agency in order to make New York City truly livable and climate resilient while bringing the benefits of safe streets to all communities, a comprehensive new report from the Regional Plan Association argues.

The report breaks down into three main areas of concern:

- Movement: It argues for a more cohesive network of bike lanes and bus-only lanes, a focus on delivery of goods in a booming e-commerce era, and reductions in space allocated to car drivers (whether in motion or stopped).

- Social quality of life: The city needs more plazas and car-free streets to serve as centers for neighborhood gathering and community-building. "Neighborhoods with limited public and park space should be prioritized."

- Climate resiliency: Car lanes must be plowed under and planted to make New York more flood-proof.

"The most important function of the right-of-way is facilitating the movement of people in the most efficient, affordable, and sustainable way," the report concludes. "Today, cars take up the vast majority of space on the right-of-way, moving the least amount of people. Instead of prioritizing the least productive, most space-intensive mode, we can rethink the allocation of space and reap the benefits of more activity space, cooling trees, storm mitigating systems, space to gather and interact, and anything else we can imagine."

As such, the Department of Transportation needs to be re-imagined to "increase its role as a custodian of public space," with the RPA dubbing the new agency, the Department of Transportation and Public Space. The idea, which puts the RPA in line with many organizations, including a call by Open Plans for a new Office of Public Space Management, is not merely a name change, but a "complete reset in how we’ve come to think of streets and their purpose."

"This represents a departure from the belief that streets are the designated realm of vehicles and toward the belief that they are a shared public resource that can bring about increased public benefit," the report says.

And concurrent with that, the new agency should immediately eliminate free parking — which constitutes the vast majority of the city's existing three million parking spaces

"Parked autos represent the most significant obstacle to achieving the vision presented in this report," the authors write.

Eliminating all parking spaces can't be accomplished without improvements to public transit, the report continues, but the benefits will be huge: the city could raise $1 billion a year (bondable to 10 times that amount) simply by expanding metered parking to 780,000 spaces, a key finding of Transportation Alternatives' 25X25 report. (Mayor de Blasio has repeatedly discussed the value of removing a small number of parking spaces for Citi Bike racks, for protected bike lanes and for the Open Streets and Open Restaurant programs, but he has resisted broader calls to eliminate a statistically significant number of spots — and has not explicitly endorsed the Transportation Alternatives plan.)

More broadly, the report's mission statement reveals a heavy lift for city officials, who cling to the belief that the public right-of-way must first serve automobiles:

The right-of-way on our city streets is a multi-purpose, public amenity that serves the greater good through diverse and flexible uses that include: mobility in all modes with reduced dominance by automobiles; ecosystem services such as stormwater management and urban cooling; community gathering and expression; and recreation, each in balance with the economic and individual needs that the right-of-way helps to support. The city serves as a guardian for these uses and helps to ensure the values of health, equity, safety, and sustainability are imbued into the policies and programs involving the right-of-way.

The call for less space for autos, better bike and bus lanes, and climate resiliency is perfectly captured in this before-and-after images of a section of Northern Boulevard in Queens:

Transforming public space

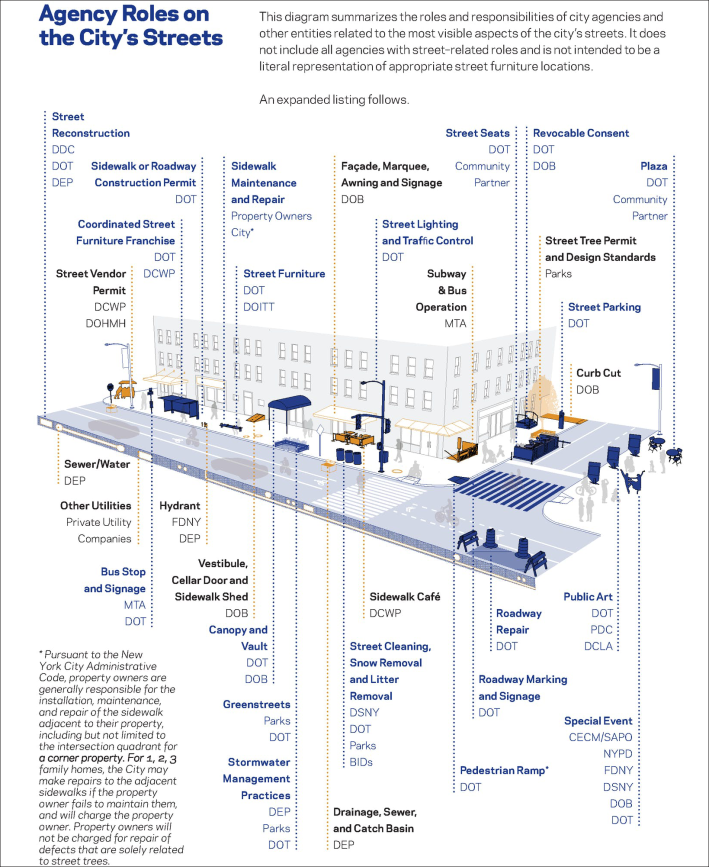

A major source of frustration for advocates is the sheer number of city agencies whose jurisdiction touches on public space: In its report, the RPA identified 18 agencies and mandated outside groups (see overlapping mandates in the attached schematic below right):

- The Department of Design and Construction

- The Department of Transportation

- The Department of Environmental Protection

- The Department of Consumer and Worker Protection

- The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

- Private property owners (remember, they maintain sidewalks).

- The Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications.

- The Department of Buildings

- Community partners (remember, the city has decided that they have to maintain street seats and plazas)

- Department of Parks

- The MTA

- The Fire Department

- The Police Department

- The Sanitation Department

- Business Improvement Districts

- The Public Design Commission

- The Department of Cultural Affairs

- The Street Activities Permit Office

The dizzying array of agencies, each exerting a limited oversight over public space, has created "a patchwork of good ideas: bike lanes that run for a stretch before running out; bioswales and rain gardens scattered in some neighborhoods while absent in others; and pedestrian or bus-only stretches limited to certain segments of certain streets," the report contends. "Aside from vehicle traffic and parking, there is no comprehensive or continuous network of street space dedicated to other uses beneficial to the public."

The entire city oversight of the streetscape should be simplified through the rebranding and repurposing of the DOT, but even that won't do much unless public and open space in the city is itself reimagined "as one interconnected place, including parks, streets, and sidewalks."

Many neighborhoods complain that the current DOT uses a "one-size-fits-all" approach to public space — jamming, opponents say, a redesign suitable for 34th Street in Manhattan onto 34th Avenue in Queens. Setting aside whether this is even accurate, RPA agrees that certain treatments — like a dedicated busway for express service, for example — might not be perfect for a quiet residential street, while a transformation of a street into a quiet seating area ringed by street vendors might not be best for a commercial strip. So the agency divided city streets into three types to characterize the general purpose of said streets (which also mirrors findings by other groups, including TA and Open Plans):

- Thru Streets (significant arterial streets where maintaining the flow of vehicles, bikes, buses, cars, and trucks is paramount).

- Activity Streets (streets that have destinations that draw people from the surrounding area, such as commercial strips).

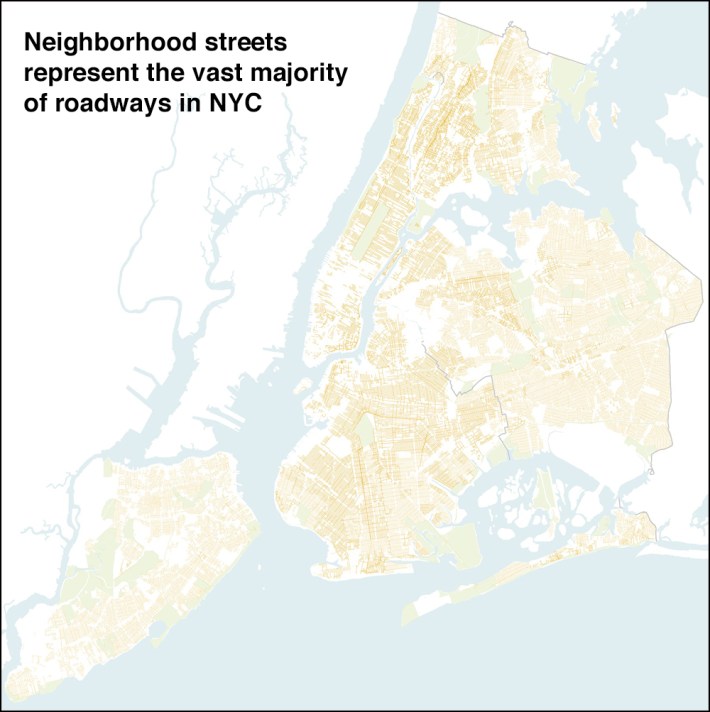

- Neighborhood Streets (low-traffic streets that primarily serve the people who live, or, in some cases, work on the street).

The vast majority of city streets are, of course, low-traffic neighborhood streets, meaning protecting these streets from unregulated car movement and storage is the most vital element of a livable streets approach.

Citing the much-studied Superblocks in Barcelona, the report offers a cherished notion of what streets could be:

Before autos dominated the space, the public right-of-way on neighborhood streets was a popular place for a variety of activities including stickball, hopscotch, jump rope, and other street games now more common in parks or other public spaces.

Parents could feel assured their children were safe because they were just out the window or up the block. New Yorkers lost this “front yard” when autos became the dominant use on city streets. Re-envisioning the right-of-way on city streets could create a new network of public commons that serve as the front yard for millions of residents. ... This system of public commons would offer something in high demand in New York City —additional space — while providing fertile ground for community building.

Streets do need to move stuff

Recognizing that New York's streets do need to incorporate the movement of goods and people, the report simply argues in favor of doing so in the most-efficient manner, especially given that 1.5 million packages are delivered in New York City every day, almost all of them by truck — and that number is expected to rise by 68 percent by 2045.

"We do not recommend reallocating all of the right-of-way away from private vehicles or even the majority, but rather finding compatibility among a variety of uses that serve the public good," the report says. "The greatest opportunity to move the greatest number of people will be through increased and improved surface public transportation (buses and streetcars), alternative transportation modes (bikes, scooters, etc), and by foot."

To this end, the RPA is again pushing its Five Borough Bikeway plan, which it first released in 2020 as a pandemic recovery plan that remains crucial now. And the organization has long championed dedicated busways. But equally crucial are truck routes to facilitate the movement of goods, but in a safe way.

"Care must be taken to preserve functional truck routes to ensure efficient deliveries," the report states. "Without this, the city faces a future of increasingly truck-clogged streets and curbsides. New and emerging opportunities, such as urban micro-distribution and a growing fleet of cargo bikes, could recalibrate how goods are moved and what space is needed, creating opportunities for changes in the right-of-way."