It's not a linear park. But it's not a car-choked sewer, either.

The Department of Transportation's long-awaited permanent design for the 34th Avenue open street in Jackson Heights calls for several car-free "plaza blocks"; nine "shared street" configurations that add space for pedestrians and barriers to slow down cars; and diverters at all of the 26 intersections to prevent thru traffic along the 1.3-mile east-west corridor between 69th Street and Junction Boulevard.

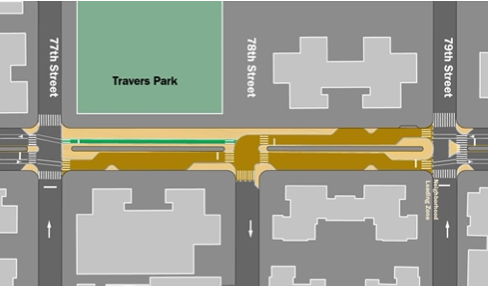

After months of anticipation, the DOT on Monday night finally revealed to Queens Community Board 3 a design for its self-described "gold standard" open street. The car-free plaza blocks would be situated on the north side of four streets — located at three schools and at Travers Park — while shared space blocks would correspond to the locations of four other schools on the strip.

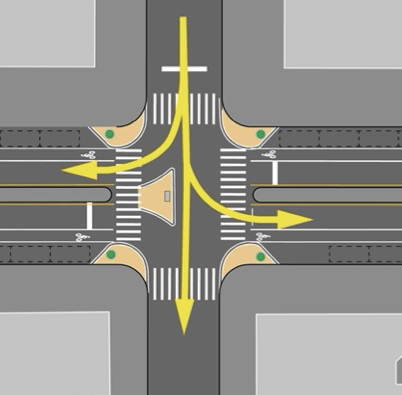

The key element of the design, however, is what the agency calls "diverters" placed at every intersection. Consisting of paint and a block of cement, the design is meant to prevent drivers from treating the roadway as the speedway it was before the implementation of the Covid-era open street program in May, 2020, while still allowing turns onto the open street from cross streets. Jessica Cronstein, an official with the DOT's street improvement program said the diverters might reduce the amount of work volunteers have had to undertake to set up and take down barriers every morning and night.

"East-west traffic is diverted off the corridor after one block," she said. "We see this as a way to set the tone for the corridor to prioritize pedestrians along the corridor while maintaining that vehicular access."

Cronstein said the 24-7 diverters helped DOT meet one of its "stated goals" for the project: "Make the street more engineered for local access and less reliant on French barricades." But other graphics in the presentation make it unclear if car drivers will truly be deterred, given that some turns will be permitted:

Here's how a diverter would work on a southbound cross street (illustration right). The yellow arrows indicate where car drivers can go. But there was no explanation why drivers moving eastbound on the strip (bottom left) could not simply veer around the diverter and keep driving. Currently, a barricade would block that route, but only until 8 p.m.

Cronstein admitted that barricades might have to remain if the diverters don't do the job of deterring thru-traffic, which has been largely eliminated thanks to the efforts of a small army of volunteers that sets up the barricades at 8 a.m. (now 7:30 a.m. to keep schoolkids safe from cars) and removes them at 8 p.m. Volunteers are getting burned out and are increasingly unavailable now that many people have returned to offices. But they may be pressed back into service.

"The goal is if we have the diverters, we don't need the barricades, but if we need them, we will bring them back," she said. (The DOT later reiterated that the goal is to reduce reliance on barricades because once the diverters are in place, barricades should be unnecessary. The goal, the agency said on background, is to have the design be durable enough that it doesn't require volunteer labor, but also allows for easy passage for emergency vehicles.)

The other main goal of the design — "Add car-free spaces where appropriate, along with shared spaces that could be made car-free for events" — is achieved through the four plaza blocks and nine shared space blocks. Such a configuration will boost the much-used Travers Park, the neighborhood's lone greenspace, whose diminutive size and singular nature explains why Jackson Heights has some of the least park space per capita in the city. Here's what the proposal looks like at the park:

The long-awaited presentation is the culmination of more than a year-and-a-half of waiting to see what the DOT would do with its most popular open street.

There is no question the open street is popular the way it currently is, as videos, stories (not just in Streetsblog) and even the DOT's own survey shows, with 77 percent of 2,212 respondents telling the agency they support permanent safety improvements. But the success of the open street has come at a huge cost: hundreds of volunteers have been forced to set up barricades every morning and take them down every night because the city open streets "program" was merely a set of guidelines — the actual work had to be done by an army of volunteers.

In some neighborhoods, that led to assaults against open street volunteers and repeated theft or vandalism of barricades. On 34th Avenue, it has created a vast majority of people who support and staff the open street and its daily programming, and a small minority of opponents who claim they were never consulted (in fact, no one was; the city created the open streets program with little discussion at the very beginning of the Covid pandemic, but then engaged in extensive community outreach starting in the winter of 2021) and now are fighting to reduce the hours, length and strength of the barricades that bar thru traffic.

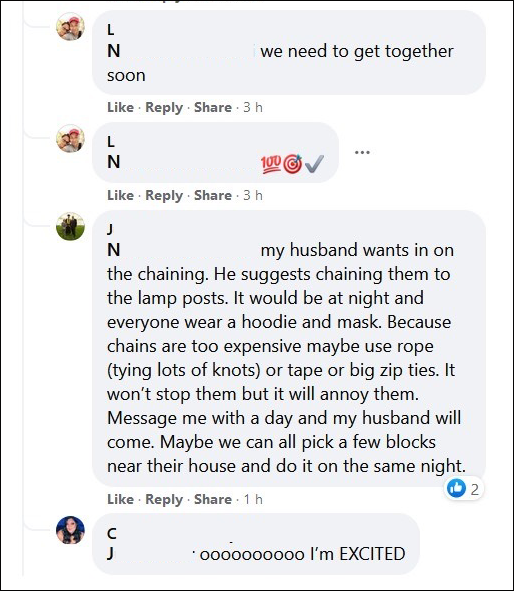

In a private Facebook group, opponents of the open street openly discussed on Monday acts of vandalism to deter open streets volunteers. "My husband wants in on the chaining," one woman posted. "He suggests chaining them to he lamp posts. It would be at night and everyone wear a hoodie and a mask. ... It won't stop them, but it will annoy them."

About three dozen opponents marched last week in protest, harassing open street users, many of whom did not realize that some of their neighbors object to open space. DOT spokesman Seth Stein described the malcontents as people who are "opposed to increased access to open space, enhanced safety for hundreds of students in the six nearby schools, as well as community-centered activities."

Meanwhile, another group of residents, who support the open street, have called for the DOT to turn the entire stretch into a linear park.

Perhaps with an eye on the toxic chat window operating in parallel to the relatively calm meeting, Banrey pointed out that the DOT is required by a law passed by the Council earlier this year [PDF] and signed by the mayor in May that not only made the open street program permanent, but defined “open street” as a roadway "on which motor vehicle access is controlled by barriers and signage or other traffic-calming measures, and on which priority is given to pedestrians, individuals using bicycles, and other non-vehicular street users."

Critics will likely point out that DOT's plan rises only to the minimum of that definition and is, instead, a capitulation to drivers, who will still have access to all but four car-free blocks on the westbound side of the two-way, divided roadway. Linear park supporters have long argued that their plan — which has the backing of future Mayor Eric Adams — is the true compromise in that it seeks to make car-free just one roadway out of scores of streets in the neighborhood where car traffic is entirely unrestricted and has contributed to more than 15,209 reported car crashes in Community Board 3 since 2016, crashes that injured 546 cyclists, 855 pedestrians and 3,142 motorists, and killed one cyclist, 14 pedestrians and six motorists, according to city stats. That's more than seven reported crashes every single day.

"The DOT proposal is a good start, but we must go further to meet this moment with bold action," said Luz Maria Mercado, speaking for the 34th Avenue Linear Park group. "We would like to see pedestrian-centered design repeated on every block. We know a well-designed linear park can properly address safety."

Meanwhile, in a text message to Streetsblog, Council Member Danny Dromm also said he was pleased by what he believes is only a first step.

"Yes, I’m pleased," Dromm said. "I am glad plans are moving forward. It’s great that the schools are involved. Giant step forward."

When reminded that he had signed the linear park petition — and that DOT's plan is definitely not a linear park, the retiring lawmaker said, "This is the first step toward that goal. A step at a time."

DOT's presentation came as the agency is under broader pressure from safe streets advocates to make its open streets program better after a report by Transportation Alternatives last week showed how few open streets are truly keeping out cars right now, a report that called 34th Avenue a "lifeline" to be preserved.

Several members of the transportation committee were concerned that the proposal would eliminate the ability of car owners, who are on average wealthier than other Jackson Heights residents, to store their vehicles in the public right of way for free (though committee members referred to that privilege as "parking"). DOT officials hastened repeatedly to say that very little parking would be repurposed for greater public good.

"We don't aim to reduce or repurpose any parking except on [the four] plaza blocks," said DOT's Jason Banrey. And the nine shared blocks would have about five parking spaces repurposed for the chicane.

Parking was also raised as an issue because the open street was also being debated at a simultaneous meeting of the local community education council. That panel backed the open street with a resounding resolution that passed with six yea votes and zero no votes, but there was some discussion, purportedly on behalf of teachers who are able to drive into the neighborhood for work because they are privileged to receive parking placards from the city, which is an entitlement that enables car commuting.

Banrey said that administrators of the multiple schools on the block have said they consider their "first concern" to be "the safety of the children," whose own commutes to school are now much safer because of the absence of cars (members of the transportation committee did not seem persuaded, with at least two asking for more parking, but the CEC resolution offered "enthusiastic" support for the open street, according to a person who had both meetings on at the same time).

Transportation Committee co-chair Steve Kulhanek, whose prior public comments suggest he is not a supporter of the open street, honed in on the diverters, which he quickly observed would be in place 24-7, unlike movable barricades that are removed every night at 8 p.m.

"That's a good nuance there, Steve," Banrey said, seeking to downplay the inconvenience of the diverter.

"It's not a nuance!" Kulhanek pointed out.

It remains to be seen whether the diverters will work. The city has had better experience proving the value of its shared street configuration, which narrows the roadway and uses paint and bollards to force drivers to drive slowly. Such configurations are working in the Flatiron District of Manhattan and in Downtown Brooklyn, though the treatment only slows down vehicles, but does not deter them.

DOT didn't do itself any favors with opponents by presenting safety statistics suggesting that injuries from crashes only fell 11 percent, from a previous three-year average of 43 per year to 38 during the open street, and downplaying the biggest news: non-injury crashes dropped from an average of 110 per year to 51. (As Streetsblog reported, injuries during open street hours actually dropped 85 percent from pre-open street 2019 to 2020, after the open street was created.)

The agency also did not appear to have a serious plan for the rising concern of super fast mopeds — which are illegal unless they have a license plate and are being operated by someone with a driver's license.

Banrey said that he hopes for "stronger enforcement efforts" from the NYPD, but suggested that the redesign can assist cops because pinch points on shared roadways will give police "areas where [they] can focus key enforcement." And shared street configurations will remind speed racers to go slowly.

The DOT said it would implement the design, which was actually initiated in 2018 after a crash on the street, in spring, 2022, meaning that the next mayor will get to decide whether to move ahead or not.

The DOT will present the plan to the full Community Board 3 on Thursday night. Details here. The agency said it is not seeking a formal vote of approval from the board.