The City Council passed a bill on Thursday mandating a robust open streets program — but that bill will take effect in three months, long after the city Department of Transportation was expected to reveal how it intended to make permanent its flagging open streets program. This story is meant to bridge that gap.

Whose compromise? Our compromise!

Opponents of Mayor de Blasio's "permanent" open streets program in Brooklyn and Queens have been crowing for weeks on Facebook pages and in group chats that they successfully dissuaded the Department of Transportation from instituting the kind of robust, car-free street program that supporters have demanded.

And they're claiming they are seeking a "compromise."

Yes, it's time for yet another deep Streetsblog dive on the state of the city's open streets program, which has been hobbled first by Mayor de Blasio's failure to lay out clear goals and then by his administration's failure to protect open street volunteers and their equipment.

First, what is a compromise?

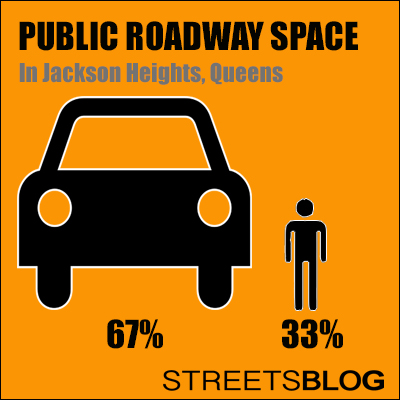

In a city where car owners have unfettered access to virtually every inch of public roadway space — and where two thirds of most streets are set aside for mere storage of cars — what does "compromise" even mean?

Supporters and opponents of the city's open streets program hurl around that term in an effort to convince the DOT that their side is the reasonable one. In Jackson Heights, opponents of the existing 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. open street on 34th Avenue between Junction Boulevard and 69th Street have said that a "compromise" would be reducing the open street to as little as a few hours a day and as little as one day a week.

Supporters of open street believe that the existing program itself is a compromise — indeed, it is just half a day on one roadway in a neighborhood catastrophically under-parked, and it must be vigilantly maintained and programmed by a small army of volunteers. A true open street, these supporters say, would be a 24-7 car-free street, with infrastructure that keeps out any vehicle except a local resident accessing a garage or a cab driver picking up or dropping off a passenger.

These open streets supporters have the numbers on their side: This week, Streetsblog counted up all the public road space in Jackson Heights and determined that drivers get the vast majority of it, whether there is an open street or not.

First, we determined the configurations of streets in the area roughly bordered by Astoria Boulevard, Junction Boulevard, Roosevelt Avenue and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. After calculating the road sizes of long residential blocks, short residential blocks, wide avenue blocks, narrow avenue blocks, and the open street on 34th Avenue, we determined:

- During non-open street hours, car drivers are allotted 67 percent of the roadway space (that is, the space in between the property lines) in Jackson Heights vs. 33 percent for pedestrians.

- When the open street is in operation, car drivers retain 65.3 percent of the roadway space in Jackson Heights.

Drilling down further, the vast majority of roadway space in Jackson Heights is set aside for the storage of vehicles not even in motion, as most roadways have two "parking" lanes. So a tiny minority of car owners locks up a plurality of the public space in the neighborhood simply to park their cars when they are not even serving the purpose of transporting someone.

And the screams of this entitled minority will likely get louder: Between 2010 and 2018, according to the census, 680 more households got a car in Jackson Heights. And the number of households that have three or more cars increased by 229. So there's a lot more new car owners hunting around for the same number of spaces that existed before they made their purchases (reminder: there is no law requiring the city of New York to find parking for a person just because he or she decided against all reasonable advice to buy a car; in fact, until the 1950s, it was illegal to park one's car overnight in many parts of the city).

Who is DOT listening to?

A big question over the past month has been the extent to which opponents of open streets are influencing the DOT against making a truly robust open street program in Jackson Heights and in North Brooklyn (how robust a plan the DOT was even considering is very much in question, given that the mayor's executive budget announced on Monday set aside $0 for capital improvements on open streets in favor of spending $4 million on more barricades and financially supporting volunteers).

The evidence suggests that DOT will not show true leadership by creating permanent car-free space — which the agency could do and still live up to its stated legal mission to "provide for the safe, efficient, and environmentally responsible movement of people and goods in the City of New York."

Safety is a well-documented benefit of the open street program. As Streetsblog reported earlier this year, crashes decreased by 85 percent during the hours of open street operation in Jackson Heights. Yet opponents still maintain that open streets are more dangerous, most recently with a North Brooklyn opponent claiming to Gothamist reporter Chris Robbins on Instagram, "We don't oppose open streets. We oppose threatening the safety of our residents in exchange for open streets."

Meanwhile, such disinformation is being repeated in private sessions that DOT is having with opponents of open streets — with opponents believing they are making headway.

"I just had a wonderful meeting with Jason [Banrey] and John [O'Neill] from DOT," one member of a private anti-open street Facebook group posted the other day. "Jason and John are listening and open to assist us in conveying our message. ... 34 OS is not a done deal as it is now, 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Jason and John are working with us believe it or not and they are our voices."

Another member of the group added, "I also had a good meeting with Jason and John and, folks, they do want to help! ... Shame on our elected officials for being dismissive." (Streetsblog obtained screenshots from an initially neutral party who now believes the anti-open streets group has gone too far)

(DOT would not make Banrey and O'Neill available to Streetsblog for an interview, just as the agency did not make their Brooklyn counterparts, Kyle Gorman and Ronda Messer, available for comment after both were shouted down at a closed-door meeting with open streets opponents earlier this month.)

DOT has been on a parallel track with open streets supporters, but none has left those interactions feeling that the agency is planning on dramatically expanding the open streets program, whether through hours or infrastructure.

"DOT does not feel empowered to draw a line in the sand and create a robust open street," said one open street supporter. "As a result, they are out there giving everyone the feeling that everything is possible."

In fact, it's likely that neither side was going to be satisfied by the DOT's approach, which explains the City Council's action this week. DOT Commissioner Hank Gutman didn't help matters recently by suggesting that everything will just be fine if the community is properly heard. Problem: He didn't hazard any guess regarding what "community" even means in a neighborhood with overall low car ownership, yet a majority of public space given to the owners of those cars.

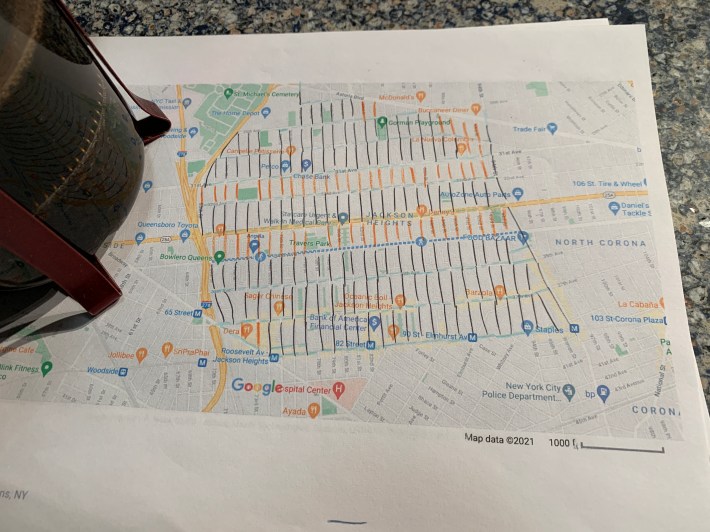

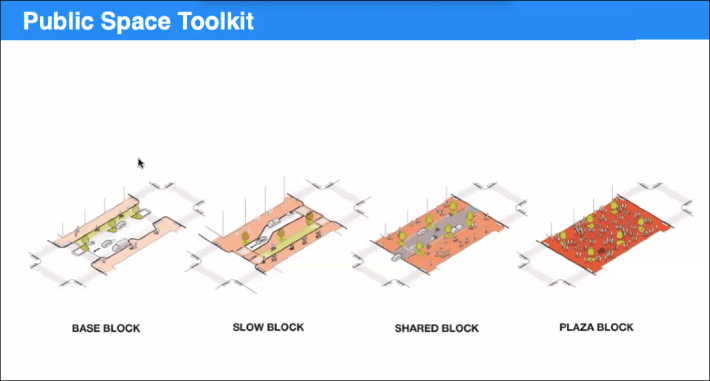

Specifically, Streetsblog asked Gutman if the DOT was considering a full pedestrianization of 34th Avenue — given that the agency had indeed presented its existing all-pedestrian design as part of a visioning session earlier this year:

A DOT spokesman had said that the plaza design would not be available to Jackson Heights residents as part of the open streets program, but Gutman suggested that it was.

"Everything in the toolbox is available if the community support is there," he said. "All of that is doable. It just requires community interest and input and then appropriate and responsible study, because it is not always the case that a community speaks with one voice, particularly when it comes to street space. We use our streets for lots of different purposes and people prioritize them differently, but the key is what the community thinks is right."

In other words ... words.

And delays. When Streetsblog asked DOT about its meetings with open streets opponents, the agency made it clear that it is willing to meet with anyone — and does.

On 34th Avenue, "following our more than six workshops, three recent bike helmet giveaways/educational outreach events and numerous conversations with community members, DOT continued its physical outreach effort to ensure residents who did not have access to virtual meetings and services were able to provide feedback about the open street and its redesign," agency spokesman Brian Zumhagen told Streetsblog. "Working with Selfhelp Community Services, Inc., DOT held its first 2021 walk-and-talk with area seniors [in eight buildings]. During this initial meeting DOT solicited feedback from 20-40 seniors during a two-hour discussion. DOT aims to hold additional walk-and-talks later [in April] as the agency continues its outreach process into the spring."

The agency said that such walk-and-talks have prompted additional requests to for meetings with DOT officials, suggesting that is very unlikely that the agency will present a design in time for the local community board's summer meeting vacation.

Where is the leadership?

In the meantime, local elected officials were completely in the dark about what DOT is planning — if, indeed, the agency was planning anything beyond the status quo.

Council Member Danny Dromm admitted that he hadn't heard anything since Mayor de Blasio gave him a commitment earlier this year that 34th Avenue would become a permanent open street (Dromm is a co-sponsor of this week's Council legislation). The word "permanent," of course, does not mean 24-7-365, but merely that there will be an open street in some form (it doesn't even mean its hours will expand or its design will be enhanced). A "permanent open street" could even mean a reduction in hours — a two-hour-every-Saturday open street on one block of 34th Avenue would be "permanent" under the mayor's definition as long as it happens every week.

"I have a commitment from the mayor for a permanent open street and the DOT is in the process of determining what that looks like," said Dromm, who favors a 24-7 linear park. "I expect to get a plan from them."

He called opponents of open streets "a small minority of people."

Perhaps, but it's a small minority of people that has successfully shut down open streets in North Brooklyn (by assaulting an open streets volunteer and stealing barricades) and elsewhere, where open streets are simply disappearing off the map:

Open street barriers, gone for weeks in the bronx. It's a vital link to the park. Who do we call to replace them or can we just take more barriers from the local precinct with the help of some responsible and respectful peace officers ? @NYC_DOT @NYC_DOTr @StreetsblogNYC pic.twitter.com/BHvfkPcLuu

— Craig Sachs He/Him (@extrapostage) April 19, 2021

The disproportionate power of the car-owning minority was even influencing open street supporter State Sen. Jessica Ramos, who began expressing concerns for "people with garages" (who are not barred from using their garages under the current open street configuration) and began calling for a "compromise."

She described the notion of a 24-7 linear park as not "realistic" even in the context of a neighborhood with the least open space in the city. (Ramos made her comments before the Council bill passed.)

"A 24-7 park sounds beautiful, but I don't know if that's realistic," she said. "As progressives, we talk about listening to all voices, but we can't only listen to those who agree with us." She said she still supported a seven-day-a-week open street, but she is willing to compromise on hours.

"The DOT's initial concept is forthcoming," she said. "I have been very clear to every stakeholder that this is an initial concept and many more community meetings need to be held, especially given the disagreement. The goal is to reduce car use and create public space, but we do have to start with the understanding that there are cars."

Over in North Brooklyn, a council candidate who is also a community liaison for the area's Council Member Steve Levin said that DOT has not been proactive. As a result, "it's become incredibly divisive," said the liaison/candidate Ben Solotaire.

"We all want the program to exist and continue and even to grow, but we're trying to figure out a way to have a conversation instead of yell," he added. "We don't want to cancel the program."

When reminded that opponents have successfully gotten the DOT to eliminate the program on Driggs Avenue, Solotaire said "there have been attacks on both sides," which is not accurate (the only attack that has required police response was the attack on open streets volunteer Rick Karr earlier this month).

Solotaire believes that the program "should not rely on volunteers," but the problem is that the DOT has not provided any way forward. (Levin is also a co-sponsor of the Council bill.)

"Their Version 2.0 had no improvement over their Version 1.0," Solotaire said, referring to the initial open streets program that was quickly introduced at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

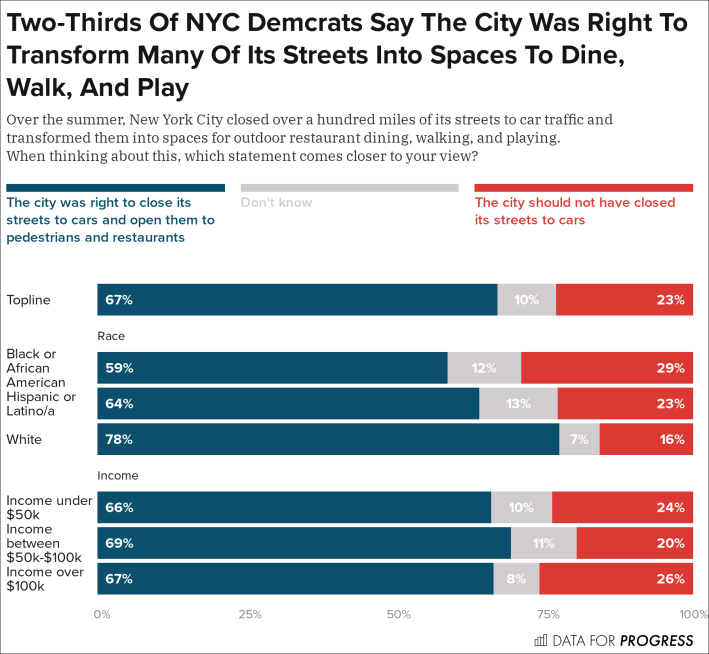

The ongoing debate all comes as there is widespread support for both the open streets and the open restaurants programs. In a survey of 591 registered voters taken in March, Data for Progress found that 67 percent of New Yorkers think the city “was right to close its streets to cars and open them to pedestrians and restaurants.” (See chart below.)

In another question, 72 percent of respondents said they prefer “livable streets that prioritize people’s needs and their safety” to 22 percent that said they prefer “streets that prioritize traffic and parking.”

The ultimate irony

Streetsblog has obtained screenshots of the chatter that takes place in opposition group Facebook pages or in chats, and the hysteria about open streets is so out of scale with reality that it is a wonder that DOT is listening to opponents at all — with car owners complaining that streets are now less safe, that they can't drive wherever they want anymore or that thousands of parking spaces have been removed from neighborhoods with open streets.

But one picture speaks volumes about the extent to which car owners are simply blind to their own contribution to destroying their own neighborhoods.

In one Facebook chat, a member of an opposition group posted the above picture to illustrate how beautiful Jackson Heights once looked.

Like most New Yorkers, opponents of open streets were quick to celebrate the beauty of their neighborhood (which, ironically, was featured in a Streetsblog story last year). Several open streets opponents delighted in the fact that the center median was not only more verdant, but also wider in the old days. And others noticed how calm everything looked. And how clean. And how ... nice.

Throughout the entire discussion of the nostalgia all the opponents had for the picture, not a single one mentioned that the reason the roadway was ruined — why the median was narrowed and defoliated, why the sidewalks were narrowed, why the curbside lanes were filled up with cars — was because thousands of residents of the neighborhood decided to purchase cars, lobby the city to allow them to store them for free on the street, and elect officials who would remake neighborhoods to accommodate the newly popular form of four-wheeled pollution factories.

If the open streets opponents truly want safe, beautiful, tree-divided, livable streets, they clearly know what they need to do: stop seeking to ban people and start seeking to ban cars.

But anti-open streets activists don't want to open their eyes — at least judging by what they write in their private Facebook groups (where at least one car owner likened supporters of safe, livable streets to Nazis).

"All this propaganda for open streets reminds me of the rise of the Nazis and how Hitler was able to gain influence on the people little by little," wrote one person in the Facebook group.

"They refuse to see 35th, 37th and Roosevelt Aves are packed with traffic. ... The assumption is that [they] know better than those engineers who came before and designed the streets. We have to STOP THIS! NO COMPROMISE!!!"

Indeed, how can you compromise with people who say they want less traffic and beautiful streets — yet want limitless access for automobiles and their storage?

In any event, that gives you a sense of the kind of reasoned discourse that the DOT is listening to right now. Will the Council bill solve that problem? That is very much in doubt.