Mayor de Blasio yesterday revealed a few more details of what he meant by a "permanent" open streets program, which turns out to be little more than an application process, a promise to support local volunteer efforts and a commitment to tailoring open streets to whatever the applicant wants.

At his daily press conference on Thursday, the mayor, who has been under fire from activists to reveal what he believes a true open streets program would look like, did not really clarify — even as his own Department of Transportation has held multiple "visioning" sessions in areas with massively successful volunteer efforts that have created the "gold standard" open streets.

"Today, we are opening applications for the open streets program, and we're welcoming community organizations all over the city to join into this effort," the mayor said, touting the application here. "We want to have lots and lots of participation in every kind of community, every ZIP code all over the city ... because we can do something amazing.

"This year we expect to have an even better approach," he added when asked later by a reporter if open streets might be configured into a network of pedestrianized areas, as some have demanded. "We want to see where this takes us. I think there's definitely room for more. How much more and how it balances all the other needs of the city – we still have a lot to work through."

DOT Commissioner Hank Gutman added, opaquely, that open streets would reflect "the appetite of the respective communities. ... The size will be in part, in large part, the principal part, a reaction to the demand by all of the respective neighborhoods. There's no set limit we have in mind."

Meanwhile, Gutman's agency has a parallel track with neighborhoods such as Jackson Heights and North Brooklyn, where volunteer efforts to maintain, promote, fund and program open streets have been so successful that many residents are agitating for "permanent" to mean a 24-7 linear park, rather than just the 12-hour a day program. The mayor said nothing about that in Thursday's comments (and, when asked for additional information, a DOT spokesperson said only, "On corridors where we're having longer-term community meetings, those discussions are happening concurrently with the operation of the existing open street. As you know, open streets was developed very quickly in response to the crisis, but we’re streamlining the program and will be working to fully integrate our existing open streets into the new processes we’re developing as part of the permanent program.")

The mayor also offered nothing new on funding for the many community groups whose volunteers have moved heaven and earth to keep the program going — many of whom are fundraising at this moment to keep what is supposed to be a city program going. He said, vaguely, that "we're working now with the Council on what's the right way to provide resources so that we can get every kind of community involved."

"We definitely need sponsorship, and one of the things that is necessary to make this work, is there's got to be an organization whether a public or a community organization, you know, involved at the site to make sure it runs smoothly," he added. "But I think we got a lot of organizations that want to do that, and we're going to try and figure out how to best help them do it."

The announcement of an application process was an odd response to waxing demand for open streets since the city announced late last year that it would be making the program permanent. The 70 miles of street segments across all five boroughs rely on thousands of volunteers setting up and removing barricades every day, replacing them when they are vandalized or damaged by car drivers, and dealing with hostilities from motorists who don't understand the program. Those community groups are struggling with material costs, volunteers are drifting away and car owners are moving to reclaim the few metaphorical inches of space that the city repurposed for healthy recreation during the COVID pandemic.

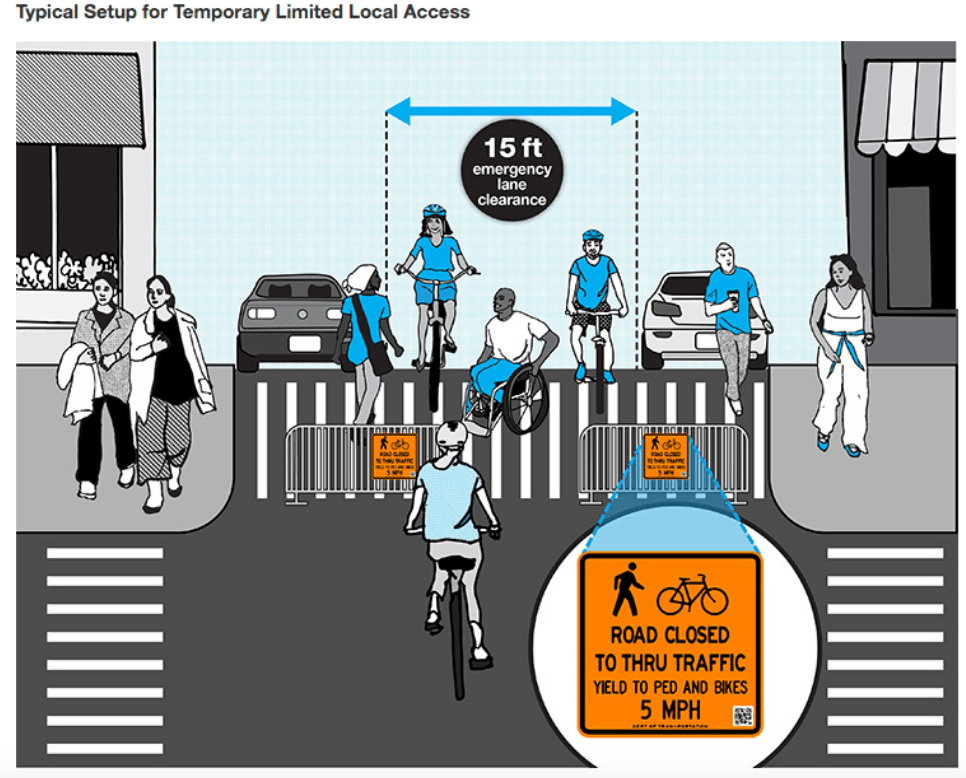

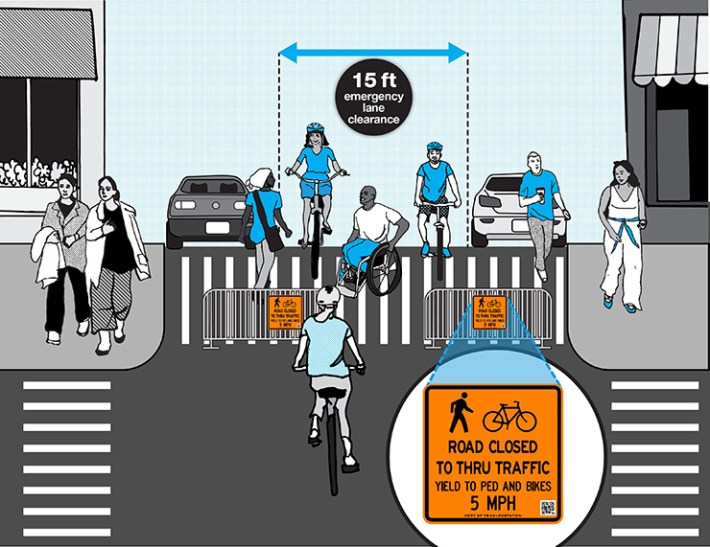

The only practical part of the de Blasio announcement was that there would be "new guidelines, "better signage," and "French barricades," instead of the wooden sawhorses that motorists turn to splinters. The city also put out images of its ideal open street:

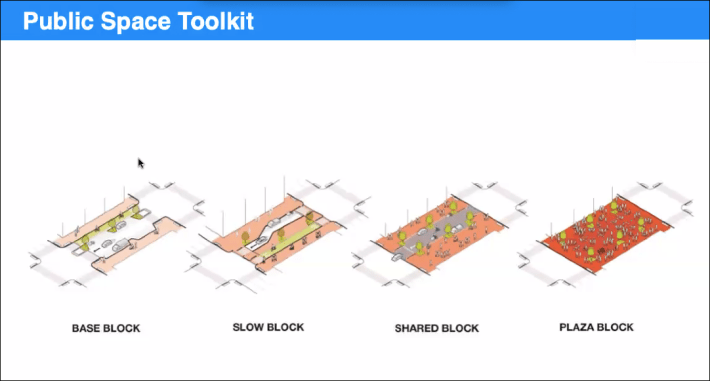

The image above is in stark contrast to other images that DOT has shown in Jackson Heights and North Brooklyn, where the agency presented its "toolbox" of solutions, including a configuration into a full plaza — a dream for open streets advocates that no longer seems possible:

When Streetsblog asked DOT for more details about what happened to the plaza idea, we got this response:

"Open Streets does not offer a 24/7 full closure option," the spokesperson said. "Anyone interested in applying for a pedestrian plaza is encouraged to submit an application they can access via the DOT website."

Reaction to Thursday's announcement was quite muted, even in the official press release, which is usually filled with glowing support for whatever is being revealed.

"The city ... must dedicate real resources to the program to ensure it is sustainable, and doesn’t solely rely on volunteers," Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams said in the release.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, meanwhile, singled out the need for "greater funding for critical local partners."

And Council Member Carlina Rivera, who gave a moving tribute at the press briefing to safe-streets activist Sophie Maerowitz, one of the forces behind the open streets in her district, likewise spoke of "equity and community investment."

In other words, "Where's the money?," the officials wanted to know.

A key to our success on #34AveOpenStreets was not having to deal w/endless red tape, forms, applications etc. SO THEY ARE ADDING LAYERS OF RED TAPE?? We are unpaid VOLUNTEERS who raise money for signage, programming. Now we have to do EVEN MORE & reapply for the privilege? Why?

— JimRockaway (@JimRockaway) March 26, 2021

Rivera also isn't taking de Blasio's word for it that the program is indeed permanent, as the mayor says. She said she wants to "codify an expanded open streets program" — that is, take it out of the realm of policy and make it a legal mandate — "so these streets become a permanent part of our city's fabric well beyond 2021."

Both de Blasio and Gutman also offered a dollop of revisionist history at the press briefing: Hizzoner dubbed open streets a "runaway success," and that's true if one considers that the program "ran away" from his initial conception of it; as readers of Streetsblog know, the original open streets program came about because of the fierce pressure of activists, and the first iteration was so over-staffed by NYPD employees that it was destined to be scrubbed.

In some more programming notes: open streets will "replace" the DOT’s Weekend Walks and Seasonal Streets programs, the agency said, so devotees of those programs should adjust their expectations accordingly.