When the MTA is finally all done with its Bronx bus-network redesign, riders may indeed get to their destinations a bit faster, but the year-long effort to improve service for the borough’s almost half-million beleaguered riders is ultimately minor tinkering that won’t solve the borough’s real transportation crisis, advocates say.

That's because the MTA, by itself, cannot address the main problem for Bronx buses (or buses in Queens and Brooklyn, where redesigns are also underway): the cars that choke the borough’s streets.

Any car-reduction plan must come from the city’s Department of Transportation, in the form of expansion of bus-priority corridors — in which buses get signal priority and street improvements to speed boarding — if not by outright limiting or banning cars to form "busways" like the one inaugurated last year in Manhattan on 14th Street. In a borough lacking any east-west subway routes, crosstown busways really are a necessity.

“The city needs to roll out the red paint in a serious way,” Riders Alliance spokesman Danny Pearlstein said, referring to the magenta hue that designates a truly dedicated bus lane.

The problem is that the bus-priority corridors claim public space presently used as car storage, and the DOT — at the direction of the mayor — seeks approval from community boards that are typically stacked with entitled car owners. That arduous process is supposed to be only advisory, but winds up costing years of effort — as ridership swoons.

“Mayor de Blasio is running out of time to make New York a fairer city. He has to go big on bus lanes the next two years, and his planners know where those bus lanes need to go,” said TransitCenter spokesman Ben Fried. “In the Bronx, all the mayor has to do is give DOT the go-ahead to quickly add bus lanes on priority streets where buses get bogged down in traffic.”

The mayor did introduce a Better Buses Action Plan in 2019 that seeks to improve speeds by 25 percent, but he has shown again and again that he has little appetite for taking on the entitled minority of car drivers that seeks to block such efforts.

The DOT has named 10 bus priority corridors in the Bronx, including:

- Pelham Parkway, Fordham Road, West 207th Street

- Pelham Bay Park Station Area

- Washington Bridge and West 181st Street

- East 149th Street

- E.L. Grant Highway

- University Avenue

- Tremont Avenue

- East 167th Street/East 168th Street

- Story Avenue

- East Gun Hill Road.

In the last several months, the department presented bus-priority proposals to CB3, CB4, and CB5 that would have cut parking spaces for single-person vehicles in favor of faster buses filled with hundreds of people. Some boards, such as 4, have been receptive, but others have balked. It remains unclear who will blink first: DOT or the community boards.

The 14th St Busway has been a tremendous success! We are committing today to make it permanent and announcing the next set of busways: 125th St in Harlem, Fordham Rd. in the Bronx, and Nostrand Ave in Brooklyn. We will roll out more every 3-5 months. Let’s get New York moving. pic.twitter.com/MoxFJdwYtC

— Competent Mayor Bill de Blasio (Archive) (@GoodNYCMayor) February 27, 2020

The department, unfortunately, isn't winning any awards for bravery. The success of the 14th Street busway — with its faster buses, increased ridership, and improved safety, all without causing the congestion its detractors predicted — has still not encouraged the DOT to designate a similar roadway in the Bronx (or in any other borough, for that matter). In particular, Bronx street-safety activists have agitated for a busway on Fordham Road, a shopping Mecca and east-west arterial like 14th Street with horrendous traffic carnage.

DOT spokeswoman Alana Morales said that the DOT is “working closely with the MTA" to build "10 to 15 miles of new bus lanes and improving five miles of existing bus lanes each year.” That's for the whole city [PDF, page 8].

It’s a drop in the bucket (of red paint).

In the Bronx, the bus-network redesign and bus-priority corridors are a pressing matter of social justice. City bus riders are on average poorer than even subway riders, according to a 2017 report of the New York City Comptroller, with an average income citywide of $28,455. That’s especially true in the Bronx. With a population of 1.43 million, a poverty rate of almost 30 percent and a median household income of $38,467 (less than half of Manhattan’s $85,066), the Bronx is the poorest of the five boroughs (and one of poorest counties in the nation).

Even given the borough’s many transit deserts, only 40 percent of households own cars, less than the citywide average of about 45 percent. If de Blasio really wants to unite the "Two Cities," as he explained his governing vision, he should prioritize buses in the Bronx.

Given the borough’s poverty, it should concern all New Yorkers that Bronx bus ridership has dropped, from 560,326 in 2013 to 456,746 in 2018, an 18-percent decrease in five years. And no wonder, when the buses have slowed to a crawl.

According to the MTA’s Existing Conditions Report, Bronx bus speeds during May 2018 averaged 6.58 mph, 12 percent below the average system-wide speed of 7.5 mph for May 2018.

Since May 2014, Bronx bus speeds have dropped overall; all but four of the 49 local, limited, and SBS bus routes have slowed — with 11 slowing by 10 percent or more, a trend that is worsening. Three routes lost a whopping 15 percent or more of their speed — the Bx19, M100, and Bx35 — all of which traverse high-traffic areas.

The MTA's network redesign has some promising features. For example, it proposes to add two new routes, and 11 of its existing 46 routes would get more-frequent service. Moreover, it would lengthen the distance between stops by 18 percent, to an average of 1,092 feet from 882 feet, which is good news for speeds because it would cut the time that the buses must wait to get in and out of traffic.

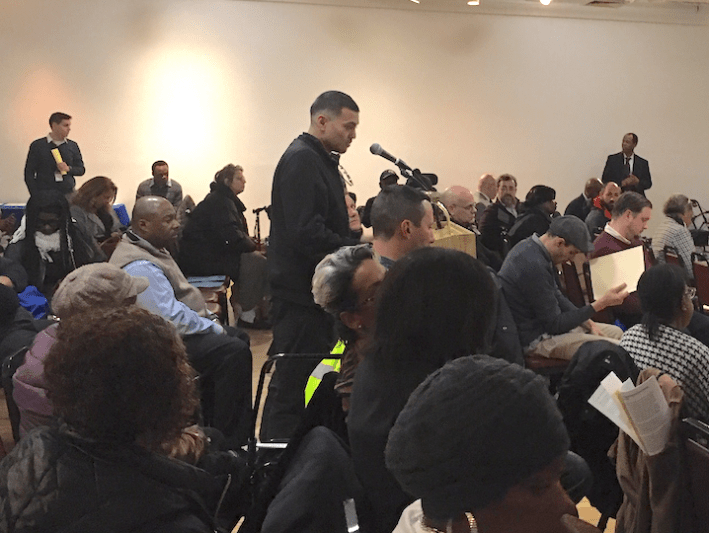

Cutting bus stops and changing routes can be unpopular, however. At the final hearing on the plan, held at the Bronx Museum of the Arts on Feb. 20, speaker after speaker rose to condemn lost stops and route changes to the Bx28 and Bx34 routes. The MTA took the criticism in stride.

“The proposed redesign updates routes that have remained largely unchanged since they were converted from trolley lines nearly a century ago, and we look forward to the feedback that we’re continuing to solicit and receive,” said MTA spokeswoman Kayla Shults.

That's good, said Fried.

“It’s good news for bus riders that the MTA will straighten out routes like the Bx36 and Bx11, run buses more frequently during off-peak hours on several routes, consolidate bus stops, and add the Bx25 and M125 routes," he said. "Wait times on many routes will be shorter, speeds will increase thanks to better stop spacing, and riders will generally be able to get more places, more reliably, in less time.”

But had the MTA taken the more ambitious approach at the outset, the benefits for bus riders could have been greater, Fried added. Given the limited mandate and a mere $2-million investment from the state, Fried said the agency should to re-evaluate the redesign in five years.

“Gov. Cuomo should recognize how important buses are to low-income New Yorkers by investing in more frequent service,” added Stephanie Burgos-Veras, campaign manager of the Riders Alliance Bus Turnaround Coalition.

But recently departed New York City Transit chief Andy Byford pinpointed the main problem at a digital town hall on the Bronx network redesign last December.

“The buses are hopelessly caught in traffic,” Byford said, name-checking the 14th Street Busway as a model he’d like to see emulated in the Bronx. “As I often say, the buses can’t levitate. ... We need to look at the root cause of why the buses are caught up. … If we can get people out of their cars and back on the buses, it’s good for New York [and] good for the environment.”

In other words, this MTA bus redesign is up to a different three-lettered agency: DOT.