City & State NY is hosting a full day New York in Transit summit on Jan. 30 at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. This summit will bring together experts to assess the current state of New York’s transportation systems, break down recent legislative actions, and look towards the future of all things coming and going in New York. Join Keynote Speaker Polly Trottenberg, commissioner of the NYC Department of Transportation, along with agency leaders, elected officials, and advocates. Use the code STREETSBLOG for a 25-percent discount when you RSVP here!

What if the BQE disappeared?

The cantilevered stretch of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway between Brooklyn Heights and Brooklyn Bridge Park has exceeded its lifespan — presenting a once-in-a-generation chance to rethink its existence by tearing it down. Will we take it? The question is timely: The panel charged with figuring out what to do with the aging highway is circulating a draft report — and may kick the can down the road to yet another panel, Politico reports.

Built in the 1950s, the 1.5-mile span of the highway between Atlantic Avenue and Sands Street is crumbling. The reflexive response has been to rebuild the highway, either in place or elsewhere. But imagine if we acknowledged that fewer vehicles are driven on the BQE in a day (153,000) than people walk through the Times Square subway station (more than 200,000) and pondered other uses for the acres of land rendered effectively useless by the BQE?

What if the BQE and its ramps did not cut through Downtown Brooklyn? How would the streets be re-stitched? What could we do with the reclaimed blocks?

To remind readers just how physically destructive the BQE is, I took the following pictures. The streets near the BQE are un-walkable, playgrounds are asthma-inducing, and the spaces below the highway are huge parking lots. See photos below:

Bridge Park #1 playground hard between the Farragut Houses and the BQE. Note the fancy, new towers on the other side of the highway. Photo: Michael King

Park Avenue (or should we refer to it as Car Park Avenue?) below the BQE viaduct. This section of the BQE infamously separates the Ingersoll Houses from Commodore Barry Park and its swimming pool. Photo: Michael King

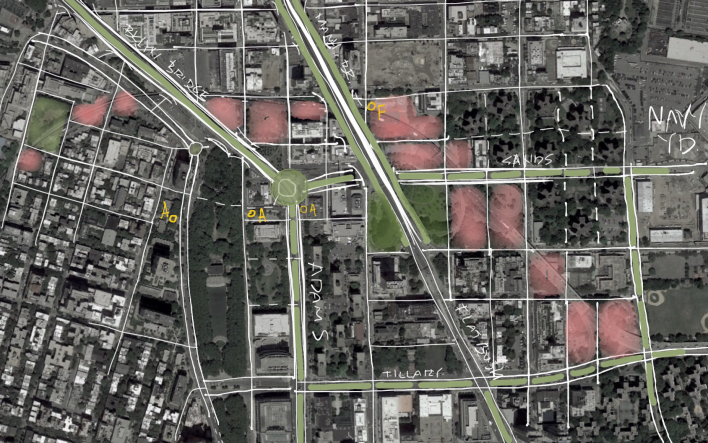

The next two images envision a Downtown Brooklyn without the BQE.

It should not be lost on readers that the New York City Housing Authority's Farragut and Ingersoll Houses are directly and negatively affected by the air and noise pollution generated by drivers on the BQE, to say nothing of the traffic.

Removing the BQE would allow us to resurrect the parks (shown in green) at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge and at the northern end of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade.

Without the ramps to the BQE, we could redesign the junction of the Brooklyn Bridge, Adams Street and Sands Street to become a giant plaza at the foot of the bridge — a wonderful welcome to the borough. Of course, we would include a much larger walkway and separated bikeway over the bridge. All this could happen because the BQE would not be pumping hordes of cars onto the bridge. Imagine such a plaza instead of the tiny, cramped stairs that the tourists now must take to get to DUMBO.

What would it take for such a transformation? To tackle fear and have a vision.

People fear traffic, and they have been convinced by the automobile lobby of the erroneous conceit that "just one more lane" is the answer to all of the congestion — instead of what it really is: a recipe for drawing more cars. But cities around the world have removed urban highways, delighting residents, and traffic has disappeared. Remember, the predecessor to the West Side Highway fell down and was removed — to the great benefit of the Far West Side and the piers.

Second, we'd need vision. A number of proposals in the last year have sought to rebuild the BQE, building bypass roads while the construction goes on. Some even dust off an $8.6-billion proposal for a tunnel underneath Brooklyn from Fort Greene to Sunset Park. Boston had its Big Dig boondoggle — do we really want one of our own?

None of the plans represents a vision to carry us forward. None addresses the simple reality that traffic is a public-health hazard, that we spend too many tax dollars catering to the wealthy in cars, and that if we do not reduce our carbon footprint, the sea is going to swallow us whole.

There are some visionary proposals, such as ones:

- to convert the BQE to a Brooklyn-Queens Park — without the expressway, or

- to dedicate the space now occupied by the BQE to the Brooklyn Queen Connector (BQX) — Mayor de Blasio's proposed streetcar, or

- to spend the money it would take to rebuild the BQE on a rail-based freight tunnel under New York Harbor. (Imagine if all your Amazon packages were delivered silently at night by rail, and then biked to your doorstep!)

The BQE is an anachronism — a failed experiment that imposed motorized vehicles on our city to the great detriment of our once-wonderful transit and freight systems.

Visionary would be not to perpetuate that mistake.

Michael King (@movethecurb) is Brooklyn-based urban designer who has worked in 22 countries on five continents, co-authored the NACTO Urban Street Design Guide, and was the first director of traffic calming at the Department of Transportation.