When Andy Byford became New York City Transit president in January, 2018, he wasn’t only hired for his technical competence. He also demonstrated talents in communication and public relations — talents, frankly, that the subways sorely needed.

In order to repair the subways’ tattered image, Byford put improving the “customer experience” front and center in his Fast Forward plan, and hired a “chief customer officer,” Sarah Meyer. They have consolidated efforts to explain service changes and progress on repair work in a “customer commitment” page, complete with an online “customer satisfaction” survey offers free rides for submitting a response.

Any New Yorker can appreciate can appreciate better communications from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. But why has the agency leaned into “customers” as its term of choice for users? Whatever happened to “passengers,” “riders,” or the old standby, “straphangers”?

Criticizing this language may seem nitpicky. But the words symbolize the political tensions at the MTA and in the city and state at large — what gets built, who pays for it and, at the end of the day, who is it all for anyway?

We as New Yorkers pay dearly for this political game. The slogan “the customer is always right” in public services — and the neoliberal notion that service users must pay their own way — cheerily papers over the attrition of our infrastructure.

That’s why language turning riders into “customers” is so pernicious. Conceptually, it obscures the subways' true nature as a huge benefit for the wealthy and the common property of city residents, and it impoverishes our language of public service.

Moreover, it produces what might be called a "bread and circuses" approach to transit policy.

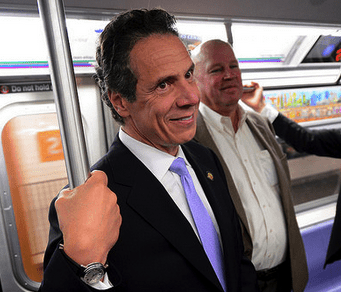

As the MTA faces a yawning budget deficit, pressure has mounted to raise fares without even a solid capital plan to reestablish subway infrastructure to last the 21st century. In order to deflect from this unpleasant financial reality, the authority has focused on fare evasion, resulting in the brutal police treatment of turnstile jumpers, often people of color. Governor Cuomo has doubled down on the "blame-the-victim" approach: This week he announced that he is adding 500 police officers to the MTA, in part to catch more fare evaders.

Several initiatives by Cuomo, such as fancy station renovations and USB charging stations, also reflect the notion that “customers” will be satisfied with surface improvements, allowing him to postpone paying the billions necessary to overhaul the hundred-year-old signals system. Meanwhile, Mayor de Blasio has attempted to score transit achievements outside the MTA system with NYC Ferry and the BQX streetcar proposal.

With “customer”-speak, Byford is playing by these cold political rules. Like many other state and federal agencies, the MTA adopted the term “customer” for service users in its media during the 1980s. After the 1970s budget crisis, the authority cleaned up and rebuilt infrastructure and launched a new fleet of cars; it enhanced its messaging in hopes of increasing ridership.

That’s understandable. After a decade in which the city lost 10 percent of its population, the MTA worried about losing its rider base to driving at a time of far less congestion in Manhattan. But appealing to riders with customer relations also reflected a new political-economic ideology: that competition between public and private services was not only positive, but inevitable.

This neoliberal creed survives today, even as the city’s population has rebounded. By neglecting to regulate the rideshare industry or to impose congestion pricing until earlier this year, city and state politicians chose to create a competitor to the subway, forcing it to focus on “customer experience” while facing falling ridership and crumbling infrastructure.

New York is not like other cities, and its subway is not a consumer product. The subway made New York America’s densest city; it’s an existential part of our life. The majority of its riders don’t own cars and rely on it as their only affordable means of travel. Most travelers to Midtown must use the subway or city streets would become gridlocked solid.

Even more so, the subway underpins the city’s economy, conveying the workers of its vibrant creative and service industries and creating the land values that enrich real-estate investors beyond reason. Political efforts to get businesses or landlords to pay more through new taxes or value capture face predictable hurdles, but they are the only just and practical way to pay for a system that will endure.

We should call riders what they are — citizens. Then we might begin to muster the political courage to keep our subways running.

Eric Schewe is a historian and Queens resident. He writes regularly for JSTOR Daily and on Twitter @nychistorybiker.