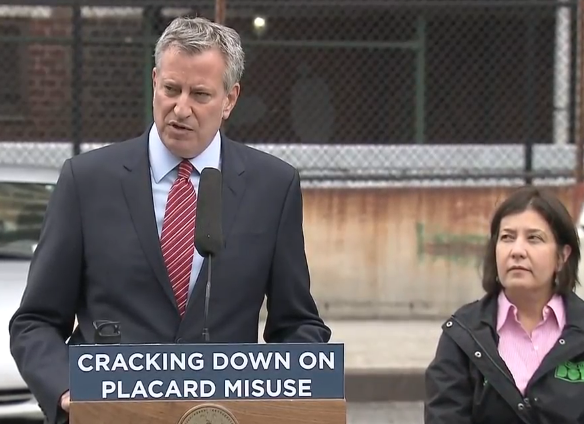

This afternoon, the de Blasio administration will release details of its long-awaited effort to curb placard abuse.

Don't get your hopes up.

If you've walked New York City's streets, particularly those surrounding government buildings, you've seen the many forms of placard abuse: there's legal (but still destructive) parking with legal city placards; there's illegal parking using legal placards; and there's illegal parking by flashing a fake placard, a Patrolmen's Benevolent Association card, an angry letter or even a reflective vest in the window.

Across the city, public officials and imposters get away with illegal and unsafe parking in front of fire hydrants and crosswalks, in bike lanes and bus lanes — and even on sidewalks. Yet the placards keep coming and coming. The de Blasio administration has continued the practice of allocating tens of thousands of existing placards, plus it doled out 50,000 more placards to public school employees, bringing the official city count to well over 140,000. That increase follows a downward trend from the Bloomberg administration, which reduced placards by more than half, according to DOT counts at the time.

De Blasio has even rebuffed attempts by the City Council to address the problem through legislation, most recently last week, when Council Speaker Corey Johnson and colleagues unveiled a package of bills. The mayor, meanwhile, continues to promise a crackdown is coming.

It's not clear whether today's announcement will alter the city's so-far meager efforts to curtail placards, or propose a more effective strategy moving forward.

Crackdowns have come and gone over the last three decades, but placard corruption persists for a simple reason: the NYPD is in charge of enforcing illegal parking — and NYPD officers are not willing to enforce basic parking laws on their own kind.

https://twitter.com/stevenbodzin/status/1029539235685130242?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1029539235685130242&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fnyc.streetsblog.org%2F2019%2F02%2F04%2Fcosta-constantinides-wants-safer-streets-and-more-parking-for-cops-in-his-astoria-district%2F

How did we get here? Fasten your seatbelts, it's time for a bumpy ride:

How does placard abuse work?

Parking placards are the ultimate perk. They give municipal employees carte blanche to park wherever they wish. And you don't even need to have an actual placard to exercise it, as the persistence of NYPD badges, guidebooks, ledgers, handwritten notes and the like on illegally parked cars demonstrates.

Very little about placards is written into actual law. Section 4-08(o) of the city's traffic rules allows for a number of different permits for "special parking privileges," including municipal parking permits, clergy parking permits, and "yearly permits for parking in contradiction to rules on city streets."

The rules vary by type permit: Clergy, for example, may park on any street adjacent to a house of worship or hospital. Municipal parking permits are limited to zones designated for the specific agencies to which they are assigned (there are signs all over town, for example, that name agencies in all branches of government where those employees are allowed to park with a placard).

And yearly permits — which are supposedly only for non-profits — allow placard holders to park in certain restricted areas, but are only valid in metered spots, truck loading and unloading zones, "no parking" areas, and spots reserved for "authorized vehicles only." Their use is explicitly prohibited in front of "no standing" and "no stopping" zones, fire hydrants, bus stops, travel lanes, driveways, and "area where a traffic hazard would be created." In other words, the cars can't become a nuisance or cause unsafe conditions for pedestrians, cyclists or other drivers. That's the law.

But placard holders know what the rules don't say: A placard in your dashboard is a free parking pass. It doesn't matter whether the placard-holder is on official business or even using the car to which the placard is assigned.

Don't believe us? Walk around any police precinct or school in the city. Stroll the streets around out government buildings in Lower Manhattan, Downtown Brooklyn, and Jamaica, Queens. Or just hop on over to the @placardabuse Twitter account, where watchdogs have been documenting the problem for more than three years.

The problem comes down to enforcement, or lack thereof. In the hands of the NYPD, it's often non-existent.

Simply put: Cops don't write tickets against other cops. And they're loath to write tickets against fellow government workers — in part for fear of retaliation for ticketing a superior. Case-in-point: In 2004, DOT traffic agent Barbara Soto-Centeno was suspended for two weeks without pay after giving a parking summons to then-NYPD Transportation Chief Michael Scagnelli, the very man responsible for the police department's traffic enforcement efforts.

“It’s notoriously difficult to enforce,” Brooklyn-based parking guru Rachel Weinberger told Streetsblog. “The alignment is wrong. You’re enforcing a crime that you’re committing.”

Count the layers of corruption, personal and institutional, today at PS 307 Brooklyn. Note the recess playground. @NYCMayor @StreetsblogNYC @gracerauh @Gothamist @StephenLevin33 @placardabuse @errollouis pic.twitter.com/TRwRfzDRVy

— JKL (@tehipite) February 11, 2019

And placard corruption isn't limited to cops. Politicians are some of its greatest practitioners. In 2017, for example, when Brooklyn Assembly Member Diana Richardson parked illegally outside of her office on Empire Boulevard district office, she posted the traffic agent's name on Facebook. (The post was eventually deleted.) Later that year, then-State Senator Marty Golden, a former NYPD cop, flashed his parking placard and threatened to arrest a cyclist his driver was tailgating in a bike lane. More recently, State Senator Kevin Parker told a GOP senate staffer to kill herself after she identified his car illegally parked in a bike lane. It does not appear than any of these people were sanctioned.

It's not clear exactly what types of placards New Yorkers typically see used to disobey parking rules. The traffic regulations make no mention of NYPD-issued placards. But it doesn't much matter — as long as you have any type of placard, your chances of getting a ticket are slim.

The report that de Blasio says he will issue on Thursday is a much-delayed follow-up to the mayor’s mid-2017 promise to crack down on the problem. At the time, de Blasio’s solution was to launch a dedicated placard enforcement unit. Since then, the city has doled out 95,228 summonses for placard abuse as of the end of 2018, according to NYPD. Around 200 vehicles have been towed.

That effect appears to be a drop in the bucket. The impact of this supposed enforcement has been negligible. The @placardabuse Twitter account repeatedly riffs on the city’s supposed crackdown — and the seemingly endless parade of examples that show it’s a farce.

What's missing? Critics argue that the mayor isn't taking the problem seriously enough.

“There has to be a will to enforce it. It’s just not complicated," Bloomberg administration DOT official Bruce Schaller told Streetsblog. "I’m sympathetic to NYPD. Why would they want to enforce this against other law enforcement? It has to be made not a choice. It has to be a directive from the mayor."

How did we get here?

It's all part of history now, but Bloomberg was far from the first mayor to attempt to tackle the placard abuse problem. In the aftermath of the Parking Violations Bureau scandals that almost brought down the Koch administration, then mayor-Ed Koch announced in 1986 plans to dramatically reduce the number of placards in circulation, from 54,000 to 15,000.

At the time, the city had fewer people and there was more space for the on-street storage of cars than today. The public concern, to the extent that it existed, was narrowly concentrated in the area of Manhattan below Canal Street where — then, as now — placard-wielding government employees were clogging up nearly all of the available curbside parking spots. That enraged businesses who relied those spots for deliveries demanded action.

To tackle the problem, Koch and DOT Commissioner Ross Sandler curtailed the number of placards and took the power of placard distribution away from more than 100 different agencies, reducing it to a committee representing just four: the FBI, NYPD, DOT, and the state unified courts system.

The "Law Enforcement Parking Committee" vetted every placard in the city, according to Shauna Tarshis Denkensohn, who served as its chair and later led DOT's Authorized Parking and Permits office.

“Part of the problem that we were solving was that there were permits being issued by every agency to whomever they wanted, and there was nobody to say no," Denkensohn told Streetsblog. "We sent out a form and every agency had to tell us who need permits and why, and then we went through agency-by-agency, job description-by-job description."

Still, police placards remained the jurisdiction of the police department — excused from the 15,000-placard cap, according to contemporaneous news reports. The blocks around police precincts and courthouses, already inundated with illegally parked cars, remained inundated. Police officers and firefighters continued to hoard sidewalk space around their station houses.

"I fought it, and we got it down, saying, 'Look, you cannot have this,'" Denkensohn said of law enforcement placard use. "There were certain precincts that took it to heart, and others that didn’t."

Sometimes in the 1990s, however, the Koch era placard committee was disbanded. Placards fell back under the jurisdiction of the NYPD. The city grew, as did its workforce. The number of placards ballooned — to nearly 142,000 by 2008.

That year marked Bloomberg's second attempt at placard reform. He had declared war on parking placards during his 2001 mayoral run, and upon taking office in 2002 ordered city agencies to cut back on their numbers. But it took another six years before the city even ventured to figure out how many placards were in circulation.

In the late 2000s, the city once again consolidated distribution with NYPD and DOT and slashed the number of placards by upwards of 50 percent. But the perk persisted — with the tacit approval of the mayor himself, who, despite his hardline stance against municipal employees' placards, continued to hand out permits to political supporters like famed salsa musician Willie Colón, who happened to serve on a city commission that met four times a year.

The progress made under Bloomberg has been reversed by Mayor de Blasio, whose administration repeatedly resists attempts at reform. There appears to be little interest in addressing the problem on a grand scale, and enforcement remains entirely insufficient. The decision to offer placards to the city's 50,000 public school teachers — the bulk of the Bloomberg era placard reduction — only compounded the problem.

Today, sidewalks and playgrounds around schools look much like the areas around police precincts. In 2019, there are at least 124,000 city-issued placards, if you believe numbers given to Gothamist by DOT earlier this week (Streetsblog's count is higher). The placards are issued by DOT, NYPD, and the Department of Education — but that only scratches the surface. Further complicating matters, placards aren't the exclusive jurisdiction of the city. Federal and state agency placards are totally out of its control. And counterfeit placards are everywhere.

"Every crackdown has been followed by a return to privileges as usual," the New York Post's David Seifman wrote in 2006.

Wait, what's so bad about illegal parking?

Parking corruption may seem trivial — it certainly does to those who commit it — but when placards are abused to occupy sidewalks, crosswalks, fire hydrants, and bike lanes, they become a serious safety concern.

The continued existence of placards also plays a significant role in the city's growing congestion woes.

On a whole, city employees are less likely to own cars than the average New Yorker, but because parking placards ensure them free on-street spots, they're actually more likely to commute by car into Manhattan. A Bloomberg-era study of placard use in Lower Manhattan showed that city employees occupied a whopping 43-percent of on-street spots in the study area. Because of that, placard reform was one of the many congestion-tackling recommendations put out by the MTA Sustainability Advisory Workgroup in December [PDF].

Enforcement, meanwhile, is inconsistent at best. Reports to the city's 311 hotline are ignored, as The War on Cars podcast co-host Doug Gordon discovered this week: Gordon filed a complaint about a placarded car illegally parked on a sidewalk. That complaint was rejected — because he did not leave contact information, which is not required. (There are countless other cases of 311 complaints mysteriously being closed. And the endless, yet never-addressed, stream of tweets directed at individual precincts or to NYPD Transportation Chief Thomas Chan show that no one is taking this issue seriously at the top.)

One of the City Council bills, co-sponsored by Speaker Johnson and Council Member Ritchie Torres, would mandate that 311 take complaints about illegal parking and placard abuse.

This is an intimidation tactic.

— placard corruption (@placardabuse) February 12, 2019

The @NYPDnews does not need anybody's contact information to respond to a complaint about an illegally parked car.

They hope "we know who you are" instills fear, and sometimes they use the contact info for harassing late-night phone calls.

In fact, as the administrators of the @placardabuse Twitter account — which has tweeted pictures of thousands of illegally parked placarded cars over the last three years — found out the hard way, NYPD officials have used that request for contact information to harass whistleblowers. That happened to one of the account's operators in 2017 — agents from the NPYD's Internal Affairs Bureau showed up at his door and told him to cut it out, the Post reported at the time.

Top police officials have shown little interest in tackling placard abuse through reform or tech upgrades. For years, they insisted it was a minor problem. More recently, in June, NYPD Director of Legislative Affairs Oleg Chernyavsky refused to endorse any of the myriad proposals from city council members to improve or reform the system — and offered no alternatives.

Even in the best case scenario, more than 140,000 city workers are getting free parking, which is a perk worth thousands of dollars each — and dramatically increases the likelihood that a worker will drive, which even Mayor de Blasio would admit is bad for the city and the planet.

So what's the solution?

Earlier this month, a possible way forward popped up on a city-owned vehicle in lower Manhattan: a barcode-emblazoned placard. That type of placard would be much harder to forge, but enforcement would fall on the judgement of individual enforcement agents, who are often loathe to ticket their fellow government employees.

It represented a reversal for the city. Three years ago, NYPD officials insisted that barcoded placards would be too easy to photocopy, and that the agency lacked the technological ability to enforce them.

Ultimately, the only real solution would be to dramatically reduce the number of placards, according to former DOT bigwig Sam Schwartz, who left city government in 1990. By and large, placards are used to park personal vehicles used to get to and from work — even for agencies like NYPD, which provides its officers with squad cars. They're simply not essential for doing the business of government. And enforcement is such a crap-shoot that presence of any placards guarantees that they will be used in ways that put the public in danger.

"Easily 75 percent of the placards probably could go," Schwartz said. "The only ones who should get placards are people who don’t use it for commutation."

Alas, the de Blasio administration is unlikely take such drastic measures as Schwartz suggested.

There are other possible solutions, however.

If government employees must get placards, Weinberger suggested the city attach a price-tag to them. That could manifest in a number of different ways: For one, the perk could be calculated into the city’s labor contracts. But that would set an unfortunate precedent of codifying placards as a right of city workers — currently, the city is merely obligated to make “the best effort possible” to provide them, according to Schwartz.

Alternatively, Weinberger said the city could replace placards with limited charge cards specifically designated for parking spots. The card would have a limited amount of money or parking hours on it. That, she argued, would force placard-holders to be smarter about when and where they use the perk.

“It helps the owner of the placard make judicious decisions about how they want to use their placards,” she said.

San Francisco did just that in the early part of this decade when it established the SFpark program, which charges market rates for on-street parking. When the program went into effect, San Francisco entirely eliminated free parking for municipal employees, and gave them the option to either pay regular meter rates or $1,000 for an unlimited parking permit.

If municipal employee unions raise a stink, the city could insist that the perk be monetized as imputed income (like a company car or other corporate perk) — so that workers would have to pay taxes on the benefit.

Another possible solution: License plate recognition technology, a common enforcement mechanism on college campuses, which would take traffic agents' judgement completely out of the equation. Municipal employees’ license plate numbers would go into the city’s files — along with those of anyone who pays for on-street parking in the city. Enforcement agents would then troll blocks, either on foot or in vehicles, scanning license plates to check whether cars were parked illegally. If not, the illegally parked vehicles would get ticketed or towed.

Today's announcement will likely fall along those lines. On Twitter, bike advocate Melodie Bryant reported that last night DOT reps told Manhattan Community Board 4's transportation committee that placards would be eliminated entirely and replaced by what Bryant described as "virtual placards issued with registration." (Correction: The concept was proposed by the CB 4 committee, not the DOT.)

Johnson's office says his legislative package and a few older placard-related bills will get a hearing next month. That may have pushed the mayor's hand. In the past, the Council declined to pass legislation due to the mayor's opposition. But things are different this time, according to Russell Murphy, former adviser to Council Transportation Chair Ydanis Rodriguez.

"If these bills pass, there are real accountability measures within them," Murphy said. "In this current council, you might see them override the a mayoral veto. It’s a little bit of a different council than it was before.”

But those bills still wouldn't get to the enforcement issues at the root of the problem. Remarkably, one proposal would explicitly prohibit city vehicles from blocking bike lanes, bus lanes, crosswalks, sidewalks, or fire hydrants — which, ironically, is already illegal. Another would require that NYPD conduct 50 targeted enforcement blitzes per week under the supervision of the Department of Investigations.

If history is any guide, nothing will change without the mayor.

This is the second in a new Streetsblog series called “Best Practices,” which will provide New York State and City policymakers with examples of how their counterparts elsewhere have solved problems and made their communities safer and more livable. Previous entries in the series are archived here.