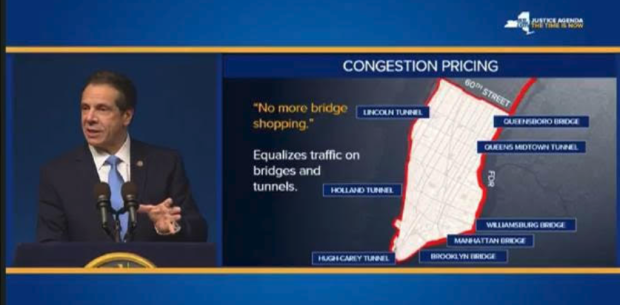

Gov. Andrew Cuomo bolstered congestion pricing with a crafty jab and a solid punch in his State of the State address yesterday. The combination bodes well for finally getting a robust toll plan through the legislature by the close of the budget session on March 31.

The governor’s crafty jab was to shape his toll proposal as a revenue target rather than as a particular set of toll rates. Not only does that keep the focus on the gain (revenue for transit) and not the pain (“They’re making me pay this stinkin’ toll?”). It also serves to discourage the legislature from undermining the eventual toll proposal with carve-outs for select roadway users, since any revenue shortfalls would have to be made up by raising toll rates somewhere else.

The solid punch is the revenue target itself: The governor called for it to be sufficient to bond $15 billion in transit investment. Using the customary 15-to-1 “debt service ratio,” whereby each dollar’s worth of annual revenue can service 15 dollars of debt, his target requires that the congestion tolls net $1 billion in annual revenue.

That billion dollars will add up to even more dollars, for two reasons:

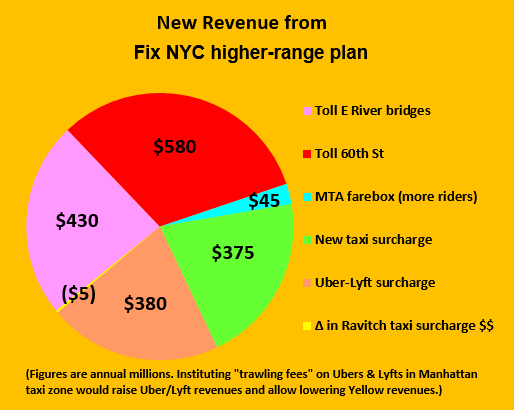

First, the $1-billion target pertains only to the cordon toll on cars and trucks. It explicitly excludes the surcharges on for-hire vehicles (yellows, Ubers, Lyfts, etc.) that must be part of comprehensive congestion pricing. These will add hundreds of millions a year, perhaps a half-a-billion or even more, as I discuss below.

Second, the implied $1 billion a year revenue target is net of toll-administration costs. Those will almost certainly exceed $100 million a year.

For comparison, let’s look at one of the most robust versions of congestion pricing laid out a year ago in the governor’s Fix NYC report — what I’ve dubbed the Fix NYC Higher-Range Plan. The cordon toll part of that plan would raise $1.01 billion annually ($430 million from East River bridge tolls, $580 million from the 60th Street tolls). When we take account of toll-administration costs, the governor’s message yesterday actually surpasses the high end of Fix NYC.

As for charges on for-hire vehicles: As Streetsblog readers know, I’ve sketched a plan that would charge FHV’s for every minute they’re carrying a fare in the Manhattan taxi zone (south of 96th Street). Ubers and Lyfts would pay an additional “trawling surcharge” for each minute they hang out in the zone waiting to be pinged — a vexing contributor to gridlock.

A surcharge program that equalizes yellows’ and Ubers’ “congestion causation” with that of private cars could raise more than $700 million a year ($460 million from Uber/Lyft, $270 million from yellow cabs) in new annual revenue. Getting such a program in place of the surcharges the legislature rushed through last March (which are now tied up in court) needs to be a priority for pricing/transit advocates.

Is there a cloud to the big silver lining I’m seeing in the governor’s address? Some are pointing to the proviso in the executive budget deferring the startup of the cordon tolls to 2021. But everyone schooled in city and state hardball politics has always assumed a two-year buildup, not just to design and build the tolling infrastructure, but to fend off litigation. In that light, a 21-month delay to Jan. 1, 2021 (assuming the bill is passed and signed on March 31) is no great concession.

What should concern transit advocates is the possible watering down of the governor’s $15-billion target by the legislature — especially when key Democrats can’t or won’t articulate a defense of congestion pricing.

Case in point: During new Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins’s turn Wednesday morning on the Brian Lehrer show, a caller fretted on behalf of an acquaintance who commutes to the central business district by car from the Bronx. Stewart-Cousins toyed with the idea of graduating the toll by income, ignoring not just the administrative costs or the lack of a sliding scale on other tolls (and transit fares), but the benefit to the Bronx commuter and all other drivers of a faster commute as some trips get priced off the streets and highways — not to mention that revenue lost at the bottom must be made up at the top to stay on track to the $15 billion.

(Lehrer didn’t help either, with his inane reference to de Blasio’s millionaire’s tax as “a possible alternative” to congestion pricing when it would raise only half as much revenue and achieve none of the traffic improvements.)

Congestion pricing has never lacked for merits — or, lately, for broad public support. It has lacked a political champion, someone who understands it, wants it and will fight for it. Judging from yesterday’s event, we now have one: Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

The governor’s budget message may be downloaded here. The section dealing with congestion tolling is on pp. 295-306.