The city and state need to move an unprecedented number of people between Brooklyn and Manhattan when the L train's Canarsie tunnel shuts down in April — and it is very far from certain that they can do it.

The current plan calls for the MTA and NYC DOT to move 38,250 people — 17 percent of the L train's interborough daily ridership — on four brand new bus lines over the Williamsburg Bridge towards SoHo and 14th Street. The plan relies on bus lanes on city streets, carpool restrictions on the Williamsburg Bridge [PDF], and a variety of untested strategies.

On Monday, the agencies hosted L-bound politicians on a tour of the corridor, but did not address several of the major unanswered questions:

Is HOV-3 enough to keep buses moving on the Williamsburg Bridge?

The peak commute plan calls for 80 buses per hour to cross the Williamsburg Bridge, where they will compete for space with trucks and passenger vehicles with three or more people. DOT claims it can move so many buses even if other users are permitted on the bridge, but experts are skeptical.

For one thing, DOT hasn't said how fast the buses will go. Transit expert Walter Hook of BRT Planning International told the Village Voice that his models indicated the buses are going to go as slow as two miles an hour.

And TWU Local 100 Vice President J.P. Patafio told Streetsblog last month that the DOT plan will fail without lanes reserved only for transit.

"(The plan) is just not going to allow the flow of bus service that’s going to be necessary for moving 40,000 people," he said. "If we don’t have a dedicated bus lane, then we’re going to be fighting for space with these ‘luxury’ services and Ubers and Chariot and those type of people."

Such services are banking on the MTA's buses to be so slow that riders abandon them and opt for alternatives, but the agencies say their service will be so strong that riders don't even consider alternatives.

"Our goal here is to try and get people to ride the most efficient modes. That is going to be buses, that's going to be bikes. It's not going to be the luxury mini-vans," DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said Monday. "Although they will qualify for the HOV lane, they won't qualify to use the dedicated bus lanes (elsewhere), so we're hoping you will still get a faster, smoother ride if you take an MTA bus."

Will local deliveries and drop-offs clog up 14th Street?

The plan also calls for 14th Street in Manhattan to be limited to buses only, plus local deliveries and drop-offs, along much of its length.

But such deliveries and taxi service hold the key to what officials are calling "the busway" between Third and Ninth avenues; drivers will be permitted to use 14th Street as long as they exit at the first right turn. The city says traffic cameras will nab the scofflaws, but the arrangement almost guarantees stalled buses as a result of heavy pedestrian traffic forcing drivers to wait their turn at lights. And drivers making drop-offs and deliveries will certainly block buses, causing cascading delays in a scheme where seconds matter.

DOT officials, citing taxi data, insist that few will actually opt to drive on 14th Street.

"Looking at the taxi data... we saw a lot of pick-ups and drop-offs happen on the avenues" as opposed to 14th Street, Trottenberg said. "If you really need that pick-up and drop-off, say you're somebody with a disability, you'll have it. If you could walk a block, you'll walk a block."

And what is the plan for 14th Street on either side of the "busway"?

DOT is planning standard SBS bus lanes for 14th Street between First and Third avenues. There, buses will run alongside regular vehicular traffic. Despite higher bus volumes, First Avenue and Second Avenue will operate as they do today, with a curbside bus lane alongside multiple lanes for cars.

But once the plan goes into effect, the buses that crossed the Williamsburg Bridge and traveled uptown on First Avenue will have to traverse four car lanes and a bike lane to turn left onto 15th Street to start their return trips to Brooklyn — a difficult maneuver as northbound cars and trucks speed through on the green light (see MTA graphic below).

Additionally, close to 10,000 former L riders are expected to use a new ferry station on the East River at 20th Street every day, and the city plans to run dozens of buses per hour from that ferry terminal during rush hours.

That's a lot of buses, but the plan calls for no bus lanes east of First Avenue.

Will construction get in the way of buses?

The city that never sleeps is also the city that never stops building. So here's another potential bus impediment: 14th Street and other streets along the bus route are the site of many ongoing construction projects and more to come.

And it's unclear if the Department of Buildings will bar any work along this crucial corridor.

New York City Transit President Andy Byford sounded an alarm that should have started ringing months ago.

"(We) need to make sure, as far as we can, all construction is complete by the time that this bus shuttle needs to go into action," Byford said after riding the route with elected officials. "What we cannot have is construction that could have and should have been completed."

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer suggested that the Buildings Department institute a moratorium on new construction during the shutdown, at least on 14th Street.

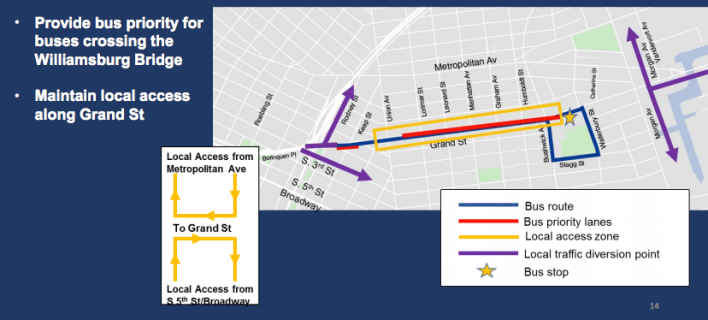

How will DOT keep traffic moving on Grand Street?

DOT's plan for Grand Street involves a bus-only lane in the westbound direction and full access for all eastbound vehicles. Thru traffic will be diverted away from Grand onto Metropolitan Avenue and Broadway, and Grand Street will be a "local access zone," the agency has said.

But how will that be enforced? The westbound bus lane will be enforced just like the 14th Street busway, with drivers penalized for staying in the bus lane for more than a block. In the eastbound direction, DOT plans to put down two blocks of bus lanes at the mouth of Grand Street, between Rodney and Keap, which should prevent eastbound traffic from entering the strip.

Even with fewer cars entering by Rodney Street, however, the eastbound lane could easily become a packed free-for-all for single-occupancy vehicles.

All the unanswered questions point to the potential for problems — but one answer officials continue to give is that nothing is set in stone. If things go awry on Day 1 or even weeks into what many call "the L-pocalyse," the agencies say they can adjust.

"With all the modeling and all the talking we’ve done, we think it’s going to work well," Trottenberg said. "If we’re finding it’s really not, that buses can’t get through, then obviously we’ll see what adjustments we’ll need to make."